Saying Goodbye To The Kojo Nnamdi Show

On this last episode, we look back on 23 years of joyous, difficult and always informative conversation.

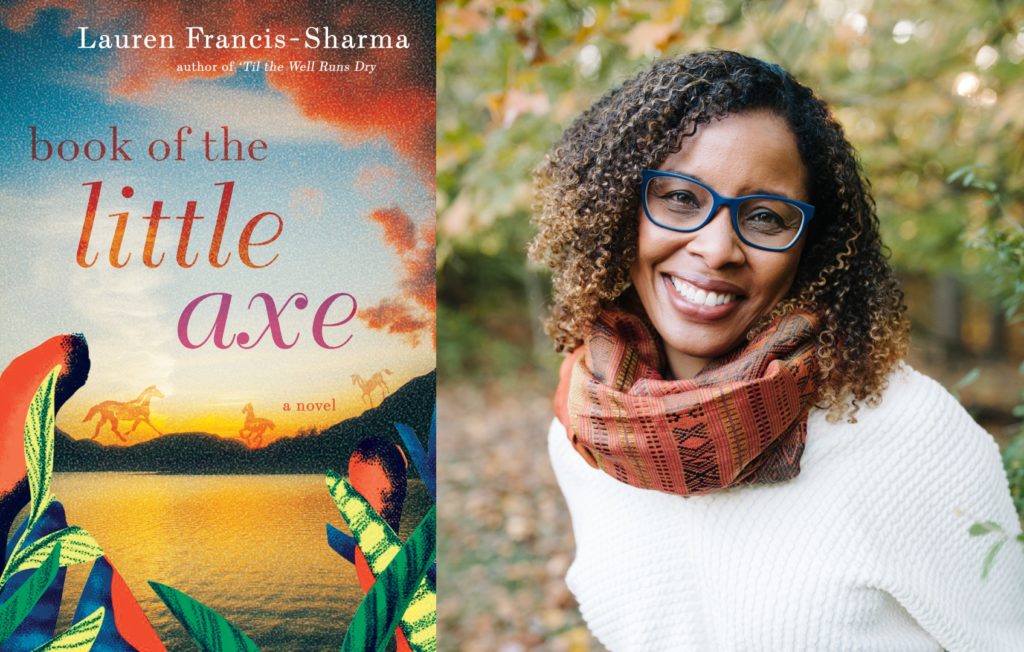

Francis-Sharma's new novel traces the story of a family across generations and cultures.

Born to Trinidadian immigrants, D.C. author Lauren Francis-Sharma wrote her first book, “‘Till the Well Runs Dry,” about the people, places and events that might have shaped her family’s story in Trinidad and the U.S.

In her latest novel, “Book of the Little Axe,” Francis-Sharma goes further back into Trinidadian history. The saga weaves together the story of Rosa, a young woman in Trinidad, navigating the island’s transition to British rule at the turn of the 19th century, and the story of her son, Victor, who grows up in Crow Nation in the American West.

Francis-Sharma joins Kojo to talk about family, identity and the joys of immersive fiction.

Produced by Cydney Grannan

KOJO NNAMDIWelcome back. In her first book, "Till the Well Runs Dry," Lauren Francis-Sharma traced her family's multicultural history through fiction, following a family from Trinidad in the 1940s to the U.S. in the 1960s. Trinidad, of course, is now known as Trinidad and Tobago. Now, the author returns with an epic story that follows a family across generations and places, from Trinidad at the turn of the 19th century, during a time of shifting colonial powers, to the American West in the 1830s.

KOJO NNAMDIWe follow Rosa Rendon as a young woman in Trinidad, rebellious, bucking expectations of her gender. And then, years later, we meet her son Victor, a member of the Crow Nation. Both grapple with issues of family, identity and belonging. Lauren Francis-Sharma is the author of "Book of the Little Axe," which is out today, from Grove Atlantic. She's also the assistant director of the Bread Loaf Writers' Conference and the proprietor of the D.C. Writer's Room. Lauren Francis-Sharma, thank you for joining us.

LAUREN FRANCIS-SHARMAThank you for having me. It's great to be back.

NNAMDIIt's been a while, but I guess it takes a while to write an epic novel. (laugh) How did you come up with the idea for this book? I've heard that you were inspired, in part, by something you heard on public radio?

FRANCIS-SHARMAYes. I was driving to pick up my children from school and listening to Terry Gross on NPR "Fresh Air," and she was interviewing Willie Nelson. And Willie was playing his guitar and strumming, and it made me think about my parents and growing up. You know, my parents are from Trinidad, and we listened to country western music in the house, like a lot of West Indians do. And we watched a lot of westerns.

FRANCIS-SHARMASo listening to Willie sing his songs really just made me think about home and think about my upbringing and think about the movies I watched with my parents. And this story just suddenly arrived. It felt very magical.

NNAMDIYour first book, "Till the Well Runs Dry," takes place in Trinidad in the 1940s through the 1960s. Why did you decide to take us to an earlier period in Trinidad?

FRANCIS-SHARMAYeah. I think that when I was promoting "Till the Well Runs Dry," it became clear to me that people didn't really understand the history of Trinidad. There were a lot of questions about whether -- why someone had a Spanish name and why someone had a French name, and where all these very different people, racially different and ethnically different, came from.

FRANCIS-SHARMASo, it made me think a lot about the history of the country and how multiethnic and multicultural it really is. And I think of Trinidad as a real melting pot. And when you go back, you realize that it all began with sort of the Spanish colonization, although you think of it as a British colony. But the Spanish held Trinidad for 200 years, and then the British came along. And there were French people who came to the island, as well, because the Spanish needed people to cultivate the island. And, obviously, there were enslaved Africans and free colored people from various islands. And so it was a real melting pot long before the British came.

NNAMDI"Book of the Little Axe" covers different places, different decades. We follow Rosa Rendon and her family in the 1790s in Trinidad, right as the British are colonizing the island. And we also go to the American West, where Rosa and her son Victor live with the Crow Nation in the 1830s. What kind of research did you have to do to accurately portray these communities during these time periods?

FRANCIS-SHARMAQuite a bit. I didn't know as much as I thought I knew about Trinidad, even though my parents are from there. So, I dug really deeply into Eric Williams' books. Eric Williams was the first prime minister of Trinidad, and he wrote several books, "From Columbus to Castro," and the "History of the People of Trinidad and Tobago." And he also had a book called "Documents of West Indian History," which really is a collection of letters and firsthand accounts from colonists writing back home to Europe, sort of about what was happening in the various colonies in the Caribbean.

NNAMDIWould you believe I just watched a YouTube video of Erica Williams Connell, the daughter of Eric Williams...

FRANCIS-SHARMAYeah.

NNAMDI...talking about the Eric Williams Memorial Collection archives at the University of the West Indies?

FRANCIS-SHARMAOh, no, I didn't see that video. That's awesome.

NNAMDIFascinating. Just look for it on YouTube. You'll see.

FRANCIS-SHARMAI will, I will. He was an amazing scholar.

NNAMDI(overlapping) Howard University graduate.

FRANCIS-SHARMAThat's right. That's right. Yes, yes.

NNAMDIHow about the research for the Crow Nation?

FRANCIS-SHARMAYeah, that was tougher, because I wasn't coming from a place of real familiarity. I had to rely a lot on Little Big Horn College out in Montana. I also found someone who helped me a lot to just get the story right about the Crow Nation and the characters, and to make sure that I was being sensitive and not infringing on practices that they don't wish to have in public.

FRANCIS-SHARMASo, there was a, you know, really -- I had a really tough time trying to make sure that I was being careful. And I approached it with incredible humility. And, frankly, you know, I think that there aren't enough materials out there on the various tribes in our county. And so it's just a little harder to find.

NNAMDIYour parents are immigrants from Trinidad, so you do have some personal knowledge, writing from a Trinidad in perspective, but you're not a member of Crow Nation. What was it like writing about a culture that you're not a part of?

FRANCIS-SHARMAScary. (laugh) Definitely, you know, it was -- I treaded carefully, and largely because I wanted to be respectful. But the story is really about a black family and it's about a black Trinidadian family. And Rosa does come to the United States or what will become the United States. And she ends up in this community of Crow Native Americans. And in order to write this story at this time and that place, I could not ignore that there were people who were different from myself and from this main character. And so to do anything other than to write them into the story as respectfully as I could would've been erasure. And I just wasn't willing to do that.

NNAMDILet's talk a bit about the character, Edward Rose. How much of Edward Rose's character did you base in history? Is much known about the real Edward Rose?

FRANCIS-SHARMAYeah, Edward Rose was a really fascinating character. And he was my anchor for this part of the story, the part of the story that takes place in modern-day Montana. He was a fur trapper, or an explorer, actually, a guide for explorers, mostly for fur trappers. And he was very well-known as a great mountain man and also a member of the Crow Nation. And it feels like he got a little lost in history, although with a little digging I sort of found one historian who wrote a very small book about him.

FRANCIS-SHARMASo, I used that book to sort of fill in a little bit more of the story. So, Edward Rose, I used the dates that he actually traveled around the West as sort of my anchoring point for the story. I knew that he had multiple wives. I don't know anything about those wives, so writing a fictional wife scene (laugh) seemed plausible. I also knew that he was black and he was black-skinned, as he called himself. And so it's known that he was at least half black and half some other tribe, not Crow. But he did make his life with the Crow Native Americans.

FRANCIS-SHARMAAnd so I just based -- as much as I could find, I tried to use that. And, you know, he was quite a hero and quite a warrior, as well. And so there are a couple of stories about Edward in the novel, and I got those from my research.

NNAMDILauren this book weaves three different narratives together. We start with Victor in Crow Nation, then traveled back in time to Trinidad at the turn of the century to see Rosa growing up. We also hear from the diary of Creadon Rampley , a traveler who has connections to the family. Why did you decide to use this narrative form?

FRANCIS-SHARMAYeah, I think that it was really obvious to me that the story needed to be told for Victor, which he's Rosa's son. Victor is a young boy, and he is searching for answers about his history. He's coming to age in the Crow Nation, and he can't seem to quite make his quest work the way that he hoped. And it seems like he's blocked by something. And that something is not knowing who he is and what his past is.

FRANCIS-SHARMAAnd so, I begin the story with Victor and his mother, and with the hopes that you become attached to me and attached to her. And then I move us to Trinidad, where you get to see Rosa as a young girl growing up on a farm that her family owns. And she's a rugged, tough woman and she's a rugged, tough girl. And it was really important for me to show sort of the parallels of their lives.

FRANCIS-SHARMAAnd, yeah, as you mentioned, there's a third narrator who -- because this book is written in the time that it's written, I knew I had to get Rosa from the Caribbean to North America. And because she is a black woman and a woman, you know, traveling alone would have been nearly impossible without, you know, her life being at risk.

FRANCIS-SHARMASo, Creadon Rampley became sort of a useful tool to get Rosa from one place to another. But what I found as I was writing him is that, you know, Rosa comes from a really close-knit family, and her father loves her. And he was not going to ever send his child off with someone that he didn't really know. And so it was really important for me to show this third person, this Creadon Rampley as, you know, yes, a drifter and a little bit of a lonely guy, and to show why he might've been the person that escorts Rosa into this new life.

NNAMDIAnd why did Rosa need to go into a new life? She is in stark contrast with her sister, Eve, who seems to be the prototypical Trinidad woman at the time. I guess they would've called her Trinidadian lady, because that's what they were aspiring to. Why did you want this struggle over gender norms to be a central part of Rosa's story?

NNAMDIYeah, you know, I think it was really important to the story to show the various ways that women and their voices and their bodies were repressed at that time. Indeed, her sister Eve is -- you know, she is a lady, and she has all the characteristics that her mother wants her to have. And she's incredibly domesticated and Rosa is just the opposite.

NNAMDIAnd, you know, I think one of the things that I love about being able to do this work is thinking about the stories of the people who haven't been written about. So, you know, when I was going through the materials, the census materials in Trinidad, people of color, African enslaved folks, everyone, they were just numbers. And it was so important for me to make real humans out of those numbers.

NNAMDIWe have stories from the white colonists, but not the stories from the people of color who lived there, who were working the land. And so the land became a real point for me, and I wanted this girl to be of the land.

NNAMDITrinidad is a melting pot of people and cultures, and this book highlights why historically this came to be. "Book of Little Axe" takes place at the turn of the 19th century. What did the melting pot look like at that point?

FRANCIS-SHARMAWow, yeah. You know, we were so much more interconnected, I guess, than maybe we imagined. There were people. As I mentioned, there were Frenchmen and Englishmen and Dutch. And this is just in the Caribbean alone, and Spaniards and native indigenous people and African enslaved people. And so there's just this huge mix of cultures and languages, as well. I mean, this book goes through French and Spanish pretty easily. The family knows French, the family knows Spanish and the family knows English.

FRANCIS-SHARMAAnd then when we move to the western part of the United States, you know, many of the people also know not only (unintelligible), but they also know the other tribes' languages, as well, the tribes within the area, in addition to the European languages. So, you know, it was about survival. It was about, you know, cross cultural, multiculturalism long before we came up with that term. This is how people were living.

NNAMDIYou know, I'm wondering if you can read a passage that sheds some light on the racism and colorism that existed in Trinidad at that time. Before going into the reading, tell us what's happening in the scene.

FRANCIS-SHARMAYeah, it's 1796. Trinidad's been colonized by the Spanish for over 200 years, at this point. As I mentioned, there are Frenchmen and negro slaves and free negroes and free coloreds and some remaining indigenous people on the island. Rosa's family is a well-regarded, land-owning family, and the scene that I will read takes place at a wedding within months of the British invasion.

FRANCIS-SHARMA“How old is this one?” The woman asking of Rosa's age with Madame Bernadette, who held a special reputation among the colored women on the island for being the loudest and most boldfaced, which in Trinidad, was saying a great deal. Nine years, almost 10, Mama looked to Madame Bernadette as if to seek approval of Rosa. “Hum, she say that's her father, ay? Goat don't make sheep. Skinny like him, too, but still (unintelligible).”

FRANCIS-SHARMAMadame Bernadette used this word that could have connoted unlearned or raw or even stupid, but Rosa knew Madame Bernadette meant to suggest that she, Rosa, was savage, for the term had come to be used by the Spaniards solely to describe the undesirableness of Africans. Several of the women and girls giggled. Rosa felt the heat rise inside her, easy-footed like it could melt her into nothing. And so she smiled, for she knew no better way to conceal how she felt. She herself had wondered if the color of her skin made her more visible or less, for it seemed to have both those powers.

NNAMDIThat's Lauren Francis-Sharma, reading from her new novel "Book of the Little Axe." This is one of many moments in the book where Rosa is criticized for her appearance. What was this a thread that you wanted to explore?

FRANCIS-SHARMAI think that, you know, at the time, racism and colorism existed, and it still does, here and in the Caribbean. And I thought it was really important to touch upon Rosa's struggle, not only as a girl in the Caribbean, but also as a dark-skinned, black girl in the Caribbean at this time. And, you know, I think as a woman of color myself, I don't know many black women who don't grow up and have these challenges to their beauty and challenges to their self-worth, particularly in an environment that idolizes European features. And so, for me, I could not and cannot write about a young black girl growing up at any time, I don't think, that doesn't struggle with this.

NNAMDIIt's my understanding that your mother may have had a similar experience to Rosa's.

FRANCIS-SHARMAYeah, she did. My father -- my grandfather was a very dark-skinned man. And he married my grandmother, who was a very light-skinned woman. And so their children -- the six of their children were varied in shades. My mother, who is probably considered medium complexioned, is and gets very dark in the sun. And so, living in Trinidad, she had kind of a rich, brown coloring.

FRANCIS-SHARMAAnd her father did not treat her as well as he treated some of the lighter-skinned siblings that she had. And I know that that was very painful for my mother, and she talks about that a lot, and how unkind he was. And this is a story that I've heard many times. And I know that it's something that runs deep, not just here in this country, but also in the Caribbean and other places, as well.

NNAMDIAnd in Guyana, where I was born, also. Let's talk about appearance. While Rosa's mother is pushing her to act more like a lady, Rosa's father Demas adores her for her hardworking nature, but he also wants his daughter to be successful in a society that has certain standards. Can you explain Demas' and Rosa's relationship?

FRANCIS-SHARMAYeah, you know, Demas admires Rosa. As you mentioned. she's very hardworking. She understands the land that they farm. She understands the horses that they're breeding and raising. And she is, in some respects, the son that his son is not, and they have a very close relationship. But something happens in the story in the family, and he begins to feel like it's his responsibility to force Rosa into a different kind of womanhood.

FRANCIS-SHARMAHe no longer feels like he can see her in the same sort of girlish, you know, tomboyish way that he once did. And he feels it's his responsibility to put her on a path where she will become a mother and a good wife and a good housekeeper. And so what's at the heart of this story is the land, and Rosa feels like it's her -- that she should have the land, that she should be able to inherit this land from her father.

FRANCIS-SHARMABut her father knows that this is impossible for a girl to be able to inherit land in Trinidad, at this time. It might even be impossible for anyone who's black, once the British come, for their land to stay with them. But he certainly knows that if it's going to anyone, it cannot go to Rosa, particularly not if she's not married.

NNAMDILauren, Victor, Rosa's son, is bullied for the way he looks. Can you tell us a little bit about Victor's search of manhood, and how that's complicated by his relationship with Crow Nation where he lives?

FRANCIS-SHARMAYes. So, Crow Nation is out in Montana and, you know, barring Edward Rose, there were very many black people, at the time, in this place. So Rosa is different, her husband is different, and so is her son. And Victor's trying to be a boy just like everyone else. He is seeking his (word?) or his vision, so to speak. And this is a very important passage for a young boy in the Crow Nation. And he's suffering a little. Not just because he doesn't quite know his own story, but he doesn't know why he's so different, why he looks so different. And that is extremely frustrating for him.

FRANCIS-SHARMAAt the beginning of the story, someone comes along outside of their tribe, who makes it really clear to him that if he thought he might have been one of the same, he certainly is not. And it's a painful moment for him to recognize that his identity is not as clear as the identity of some of his friends.

NNAMDIFascinating story. Most authors go on a book tour to promote their book, and now everything is virtually remote, just like this interview. This Saturday, at 3:00 p.m., you'll take part in a Politics and Prose virtual event for your local book launch. What's it like having to do the book tour virtually?

FRANCIS-SHARMA(laugh) A little frustrating, because I love being with my readers. And I'm the kind of author, I think, who I hug people and I shake a lot of hands. And all that's really different and really going to change, I think.

NNAMDI(overlapping) Nevertheless, you will enjoy this virtual event, and it will be a success. At least that what I say.

FRANCIS-SHARMAI hope so.

NNAMDILauren Francis-Sharma, thank you so much for joining us.

FRANCIS-SHARMAThank you. Thank you for having me.

NNAMDIOur conversation with Lauren Francis-Sharma was produced by Cydney Grannan. Our discussion about Child Welfare Services was produced by Kayla Hewitt. Next Tuesday evening, we're hosting a virtual town hall on navigating the post-pandemic job market. Whether you're a new graduate, recently unemployed or someone who's been on the job hunt for a while, we'll dig into what you can do to be competitive in this new employment landscape and get hired. It's a free virtual event, but you do have to register to get the link. You can find all the details at kojoshow.org.

NNAMDIAnd we'll hear excerpts from last week's virtual town hall on parenting during the pandemic on tomorrow's show. Until then, thank you for listening, and stay safe. I'm Kojo Nnamdi.

On this last episode, we look back on 23 years of joyous, difficult and always informative conversation.

Kojo talks with author Briana Thomas about her book “Black Broadway In Washington D.C.,” and the District’s rich Black history.

Poet, essayist and editor Kevin Young is the second director of the Smithsonian's National Museum of African American History and Culture. He joins Kojo to talk about his vision for the museum and how it can help us make sense of this moment in history.

Ms. Woodruff joins us to talk about her successful career in broadcasting, how the field of journalism has changed over the decades and why she chose to make D.C. home.