Saying Goodbye To The Kojo Nnamdi Show

On this last episode, we look back on 23 years of joyous, difficult and always informative conversation.

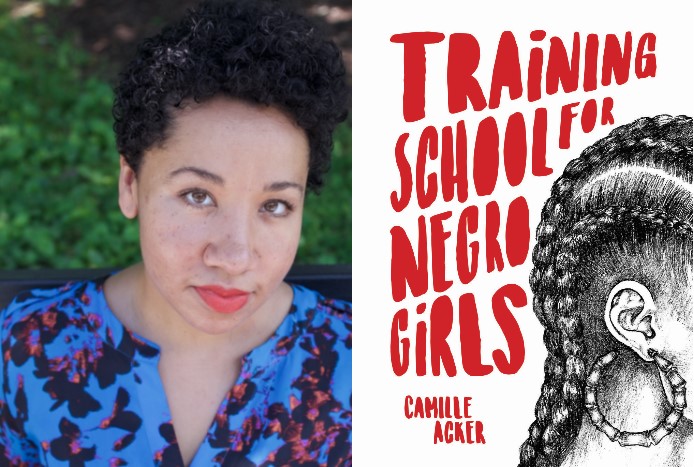

Camille Acker’s primary characters are fifth grade teachers, aspiring pianists, high school students, sculptors, and T.S.A. agents — all navigating race, gender, and the narrow expectations of who they’re supposed to be as black women.

“Training School for Negro Girls,” divided into two parts — “Lower School” and “Upper School” — offers glimpses of black women sometimes coming into their own and sometimes floundering in the city.

Acker joins us to discuss her new book — and her own D.C. upbringing.

Produced by Julie Depenbrock

MR. KOJO NNAMDIWelcome back. Camille Acker's debut collection of short stories traces the lives of black women and girls in Washington, D.C. across different neighborhoods, across different socioeconomic statuses as they navigate race, gender and narrow expectations of who they're supposed to be. The book is called "Training School for Negro Girls." And joining us to discuss it is the author, Camille Acker. She holds a BA in English from Howard University and MFA in creative writing from New Mexico State University. Camille Acker was raised in D.C.. She currently lives in Philadelphia. Thank you so much for joining us.

MS. CAMILLE ACKERThank you for having me.

NNAMDIEach story in this collection is different course -- of course but what would you say is the thread that runs through the book?

ACKERI think self-discovery is a thread throughout the book. Each of these characters are coming to moments in their lives where they're having to think about the family that they've come from, the world that they've been inhabiting, and their own ideas about themselves. So the idea of school as an education, all of these girls and women are getting an education about who they are.

NNAMDIThis book begins with a quote from one Nannie Helen Burroughs. Who is she and how did her life influence your writing?

ACKERI knew Nannie Helen Burroughs name because of the street in Northeast.

NNAMDIYou grew up in Northeast...

ACKERI did.

NNAMDI...and everybody, who goes by there says, Nannie Helen Burroughs Avenue?

ACKERYes, exactly.

NNAMDII got to check out who is this, yeah.

ACKERYes, exactly, exactly. But it wasn't until I was in grad school and I was taking a Chicana and black feminism class that I started to explore more about Nannie Helen Burroughs. And she was an educator. She gave a speech to the National Baptist Convention in 1900 where she was advocating for black women's greater participation in the life of the church. And when she opened her school in the early 1900s, which was part of an era of a number of training schools, she wanted black girls and women to have job skills. But there were also skills about women being ex -- expert housewives and learning domestic skills.

ACKERSo it was still this need to sort of train black girls to be what white people, what men expected of them. And so I started to think a lot about training and how we all get trained by society, by culture, by our family and how we internalize those messages.

NNAMDIAs a result the book is called "Training School for Negro Girls." I think Nannie Helen Burroughs would've been proud of you.

ACKEROh, (laugh) thank you.

NNAMDIYour primary characters are 5th grade teachers, aspiring pianists, high school students, TSA agents and sculptors all living in different parts of the district. The New York Times said in a review of "Training School for Negro Girls" that quoting here, "The characters share a shrewd understanding of the narrow perceptions they face as black women. When underestimated they're often fiercely, beautifully unyielding." To what extent were you writing these women from your own experiences?

ACKERWell, I have a mentor who says in the old saying, write what you know, that he says it's really, write what you emotionally know. And so there's emotional touchstones in each of those stories for me, about belonging, about navigating family relationships, about love and intimacy. But there are also ways that I was certainly, you know, deeply influenced by my growing up here of intersections of -- of class especially with race. And so that really, you know, comes out in the book. I've talked before, I grew up in Northeast, but I went to school in Upper Northwest. And so...

NNAMDIWilson High School.

ACKERWilson High school, that's right. Exactly. So navigating that difference, you know, was -- was something that I encountered and -- and something that I wanted to bring out in the collection with the stories of -- of these girls and women.

NNAMDICamille, D.C. is your hometown. You grew up in Northeast Washington and as we mentioned earlier, attended Wilson High School, earned your degree in English at Howard University. In an article for D.C. Line you told our own Tayla Burney -- well, she's formerly a producer on this broadcast, you said, we all create our own city, where we go, where we grew up. What was the city for you growing up?

ACKERWell, what I loved about growing up in D.C. was that it -- it was a-it's a city with all the access and the culture that -- that an urban environment has. But it also felt like a place that I could know, you know, rather than a much larger city where sort of the anonymity, you know, that's what you're always navigating. But here it felt like there was connection and community. And so, you know, my parents would take us to the Smithsonian and we sort of had all of that access, international, you know, way that D.C. as a city, but then I also felt like I was never going to be lost here.

NNAMDIAnd then you moved to New York.

ACKERAnd then I moved to New York (laugh) and experienced exactly what it is to sort of feel lost in a large city, yeah.

NNAMDIYeah, there's something about D.C., even though it's technically defined as a major city or a big city...

ACKERYeah.

NNAMDI...there's something about D.C., as you say, that kind of makes it knowable...

ACKERYes.

NNAMDI...if you've been here long enough that's a lot more difficult if you were in, oh, New York or (laugh) Chicago or Los Angeles...

ACKERYes, yes, yes.

NNAMDI...to know the city. You can have a kind of ownership of D.C. that you feel here if you've been here for a while. You didn't pick that up in New York?

ACKERNo. I think that was a lot harder to navigate. I felt more like -- I lived in Brooklyn and so I felt like I could navigate sort of knowing my little part of Brooklyn. But, yes, I think -- you know, and having lived in Chicago too, that D.C. does feel -- there's the intimacy of it which is something that I really loved growing up here. And that even, you know, when I come back that I always feel...

NNAMDII'd like you to read an excerpt from your book.

ACKERSure.

NNAMDIYou can take it from the first story in your book called, "Who We Are."

ACKEROkay. We walk down the halls like we are coming to beat you up. Even the teachers move out of the way. No one wants to catch an elbow in their ribs or a foot in their stride. They look away when we pass or take a turn down a hallway where we are not. We will make them into a joke anyway, something about their face or their clothes or their name. We decide who they are.

NNAMDIWho are you writing about here? Who is we and why are these girls so, well, fierce? (laugh)

ACKER(laugh) Well, yeah, so they're -- a collection of girls in high school, who I think when you read that story you can think, well, they're sort of wreaking havoc, but there's also layers to them. They're also desires and needs and wants that they're expressing. And I think that in that navigation of class, and race as well, that they're recognizing that there's a power that they don't hold. And so by the end of that story part of what they're trying to do is use what they have, the tools that they have to feel powerful.

NNAMDII'll tell you what I picked up reading that story was that here's -- here was a group of young girls, who in a lot of ways felt invisible.

ACKERYes.

NNAMDIAnd they had to demonstrate, I am here.

ACKERYes.

NNAMDIWe are here.

ACKERYes, absolutely.

NNAMDII picked up the right thing?

ACKERAbsolutely you did.

NNAMDIYes.

ACKERYou got it. You got it.

NNAMDI(laugh) 800-433-8850. Have you read Camille Acker's book of short stories, "Training School for Negro Girls?" Tell us what you thought. Readers will recognize Washington in the pages of your book. You write about crab feasts and cicadas, neighborhoods in Southeast and Upper Northwest. And figures like Len Bias, Marion Barry and even Marvin Gaye, who looms especially large in your final story. Why focus on those men in particular?

ACKERWell, I wanted this collection to really be steeped in blackness and to be steeped in cultural touchstones. And I think the three of them, especially for this area, are cultural touchstones in that way and touchstones for me as well. I remember Len Bias dying and I remember going to the assemblies, the just say no assemblies that his death sparked. You know, Marion Barry on the FBI tape with the arc also of being re-elected. And Marvin Gaye and his music, especially his album "Here, My Dear" were really important to me in writing this collection.

NNAMDIWell, let's listen to a little bit of "Here, My Dear."

NNAMDIOf course we claim Marvin Gaye as our own, but how did his album "Here, My Dear" figure into the story?

ACKERWell, so in that last story it's a father and daughter driving around D.C. listening to a show that's dedicated to Marvin Gaye. And, you know, I think that -- that album, what he's talking about in it and also even, you know, sort of reflecting back with Len Bias and Marion Barry of this tremendous talent and -- but also people who then make mistakes. And so how do we -- how do we think about someone's legacy when, you know, they've -- they've encountered difficult times in their lives? And so in that is that daughter and father are talking about having made mistakes and what does that mean about how they see themselves after.

NNAMDIWe got a tweet from the Bibliophile, who says, so excited to hear Camille Acker on the Kojo Show talking about her short story collection and repping Northeast D.C.

ACKER(laugh) Yes.

NNAMDIOh yeah, we -- we rep whatever ward of the city we happen to have been born in...

ACKERYes.

NNAMDI...or grew up in.

ACKERYes.

NNAMDIIn your short story collection, which is divided into two parts, lower school and upper school, there's another tale called "Mumbo Sauce" that we really need to talk about. Can you give us a brief summary of "Mumbo Sauce?" Not the sauce, because we did a show about that here (laugh) a few weeks ago.

ACKEROkay, okay.

NNAMDIBut a brief summary of the "Mumbo Sauce" story.

ACKERYes, yes. So Constance and Brian are an interracial couple who moved to D.C. from Brooklyn, moved to Northeast. And Constance is a sculptor and so she's at home a lot doing her work, but she begins to explore her neighborhood. And exploring it finds this neighborhood carryout. And the owner and the longtime customers there embrace her but she -- when she finds out that it's gonna be closing due to gentrification she decides that she's gonna do something about it without having talked to them about whether they want this place to be saved.

ACKERAnd so in the end it's her navigation of her own race and how she's interacted with, you know, these folks who are at this restaurant but also how she's feeling about her interracial relationship.

NNAMDIYeah, she's gentrifying the neighborhood even though she herself is African American. And she's making assumptions about what she thinks people want and what she thinks people need. So I'm wondering...

ACKERThat's exactly right.

NNAMDI...if you can read another excerpt for us, this time from "Mumbo Sauce."

ACKERYes. Gentrification was always good at first, fresher produce at the grocery store, a cleaner subway station. Then a new shop replaced the family-owned one that had been there for decades. The crumbling roadhouse, an eyesore for its boarded up windows, but beautiful when the first snow collected in the jagged remnants of its roof, it's gone one day to make way for high-rise condos.

NNAMDICamille Acker. She's the author of the short story collection, "Training School for Negro Girls." She was just reading from the short story "Mumbo Sauce." You do not shy away from complexity in your characters or in the way you talk about the District of Columbia, which is certainly a city that has changed dramatically during the course of the last 20 or 30 years. How did that backdrop of gentrification play into both your thinking and into your writing of these stories?

ACKERWell, when I decided I -- my writing wasn't always about D.C., so when I started to write about it I knew that I needed to also navigate this changing city, that's it's -- certainly it's changed since I graduated from Howard. It feels like it changes every time I come back and see my parents. And so I wanted to think through that and that's -- gentrification is certainly something that's confronting so many cities.

ACKERAnd so what does it mean when a place changes and what does it also mean when you're one of the people, who's causing change in a place? And how is that reflected in the way that that character in that story is thinking about herself but also, you know, in real life, how -- how we navigate that identity when the place that we are is different.

NNAMDIBecause one of the only things that's certain is change. I remember...

ACKERYes.

NNAMDI...our D.C. delegate Eleanor Holmes Norton talking about the fact that she grew up in a predominantly white city, Washington. D.C. That was not the city that you grew up in.

ACKERIt wasn't, no.

NNAMDIAnd the city you're seeing now...

ACKERYeah.

NNAMDI...is not the city that you grew up in either. So many of your characters are therefore skilled at the art of code switching. For listeners who may not know, what does it mean to code switch and why is it necessary in a place like the District?

ACKERWell, I think about code switching as being bilingual, that there is a language that you talk about and that you talk, have a rhythm and the words that you use when you're with family and friends, black folks talking to black folks. And then when you go to predominantly white spaces, you know, whether that's your job or university that you go to, that you're navigating in a different language. And doing that is -- has been often necessary to, you know, assimilate your identity into -- to, in some ways, make people comfortable with you and being able to communicate in a particular language.

ACKERAnd so especially for this city, you know, which you rightly point out as predominantly black when I was growing up here, a chocolate city, of navigating that feeling of home and intimacy of being with other black people. And then also how does that shift and change when you are not using the same words, right (laugh) or using the same dialect when you're -- when you're talking with other people.

NNAMDISo many of these women have a yearning to belong. One character writes in final draft of a college essay, quoting here, "I am my own kind of black girl however, I do not know if I am the kind you would want or not." That's such a relatable sentiment. Is it something you felt at all as you came into your own as a writer?

ACKERYes. There was definitely a navigation of that as I was writing. I -- at one point, sort of wanted to be Toni Morrison, because I think (laugh) almost every black girl, who is writing, you know, wants to be Toni Morrison.

NNAMDII'm the next.

ACKERYeah, exactly, exactly. I read the "Bluest Eye" when I was 16 and it was deeply influential for me. But at some point I also had to realize that I had to write my own experience, that, you know, I was not raised in Lorain, Ohio and, you know, I'm not from the same generation that Toni Morrison is from. And so how could my writing be reflective still of blackness and femaleness as her writing is but how could it also include where I'm from, the era that I was raised in. And so that journey of really finding your true voice is true for every writer.

NNAMDIWe got a tweet from I. Mobley. Camille Acker's telling complex stories about D.C. culture and the lives of D.C. residents with a loving embrace of complex black lives, loving all things D.C. and hearing so much of my own experience in Acker's. I'm really appreciating this segment. Well, thank you very much, I. Mobley. Your book was published by Feminist Press. What can you tell us about Feminist Press?

ACKERSo Feminist Press was founded in 1970 and in that era of second wave feminism and mostly they started out reprinting books, so reprinting books from women writers including women of color like Zora Neale Hurston and Dorothy West. But then they started to print -- publish books by writers, who had not been published before including Louise Meriwether, who wrote "Daddy Was a Numbers Runner."

ACKERAnd she was actually the inspiration for the way that I came to Feminist Press which was through a contest for a debut book by a woman of color called the Louise Meriwether Book Prize. And I entered it. I didn't win it, but (laugh) they loved the book and wanted to publish it. And it brought actually a few other women to them whose work has come out over the last year.

NNAMDIYou dedicated this book to all the black women close to my heart and to the two who are closest. They both share your last name, Fay Acker and Juliette Acker. Who are they?

ACKERThey're my mother and my sister. (laugh)

NNAMDIAnd why'd you dedicate the book to them?

ACKERBecause they have been two of my biggest champions, not just with this book but also in the years before that when I doubted about being a writer about whether I would ever have anything published. They really encouraged me to call myself a writer and believed in me when I didn't often believe in myself. (laugh) So that kind of cheerleading was so important to getting to where I am now.

NNAMDICamille Acker is the author of the short story collection, "Training Schools (sic) for Negro Girls." What's next for you?

ACKERI'm working on a novel, so that's in progress. (laugh) And I have a few other book ideas and I'm also currently teaching an MFA program so hoping to help inspire some new writers.

NNAMDIWell, good luck on your new book.

ACKERThank you.

NNAMDIAnd that's it for today's show. Today's show with writer Camille Acker was produced by Julie Depenbrock. Our discussion on Montgomery County's bike plan was produced by Mark Gunnery. Coming up tomorrow, we remember Washingtonians we lost in 2018 from a Taekwondo grand master, who popularized the martial art in the U.S. to a go-go legend who helped define the genre in Washington.

NNAMDIAnd of course I should remind you that Camille Acker's book is called "Training School for Negro Girls." It was publishing in October. Join us tomorrow to reflect on the legacies of Washingtonians, who passed this year. It all starts tomorrow at noon. Until then thank you for listening. I'm Kojo Nnamdi.

On this last episode, we look back on 23 years of joyous, difficult and always informative conversation.

Kojo talks with author Briana Thomas about her book “Black Broadway In Washington D.C.,” and the District’s rich Black history.

Poet, essayist and editor Kevin Young is the second director of the Smithsonian's National Museum of African American History and Culture. He joins Kojo to talk about his vision for the museum and how it can help us make sense of this moment in history.

Ms. Woodruff joins us to talk about her successful career in broadcasting, how the field of journalism has changed over the decades and why she chose to make D.C. home.