Saying Goodbye To The Kojo Nnamdi Show

On this last episode, we look back on 23 years of joyous, difficult and always informative conversation.

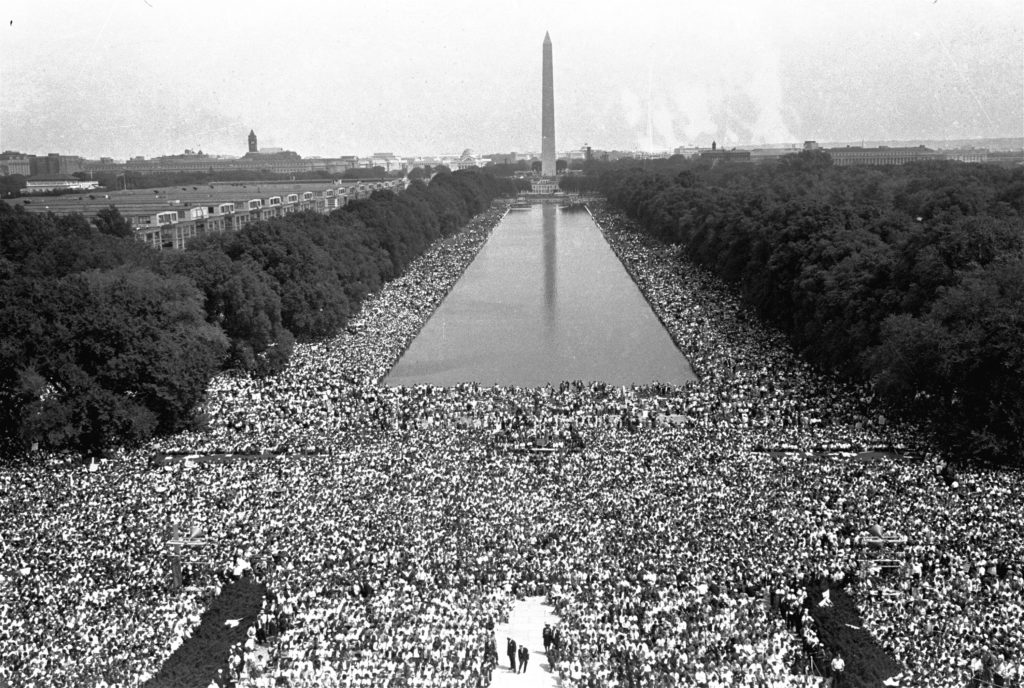

Crowds are shown in front of the Washington Monument during the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, August 28, 1963.

Friday is the 57th anniversary of the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, where Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his “I Have a Dream” speech. In reference to the killing of George Floyd in May, organizers are calling this year’s march the “Commitment March: Get Your Knee Off Our Necks.”

This year’s March is being led by the National Action Network, with a virtual march being organized by the NAACP. We spoke with representatives from both organizations to learn what to expect at Friday’s marches, as well as with the National Museum of African American History and Culture’s Aaron Bryant and Congresswoman Eleanor Holmes Norton.

In 1963, marchers rallied to demand economic and social justice. So, how far have we come almost 60 years later, and what do today’s organizers hope to achieve?

This is a broadcast of the audio from our Kojo In Your Virtual Community event on August 24, 2020. Kojo will not be taking live calls or questions through social media during this show.

Produced by Kurt Gardinier

KOJO NNAMDIYou're tuned in to "The Kojo Nnamdi Show'' on WAMU 88.5. Welcome. This week, we held our latest Kojo in Your Virtual Community event via Zoom. The topic this time, "March on Washington 2020: The Commitment March." WAMU's Jeremy Bernfeld assisted me again by moderating and sharing the questions from the hundreds of attendees. A quick programing note, our next Kojo in Your Virtual Community will be in late September. Details on that event will be posted to kojoshow.org. So, look out for that. And a reminder, today's show is pre-taped, so we won't be taking calls or reading your questions or comments from social media during the broadcast.

NNAMDIFriday will mark the 57th anniversary of the 1963 March on Washington. The march brought hundreds of thousands of people from all across the country to the National Mall. This is where Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. delivered his famous "I Have a Dream" speech. The official name of the 1963 march was the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. So, the focus was not just on civil rights, but on economic rights, as well. Here's Dr. King.

DR. MARTIN LUTHER KING JR.One hundred years later, the Negro lives on a lonely island of poverty, in the midst of a vast ocean of material prosperity. One hundred years later, the Negro is still languished in the corners of American society and finds himself in exile in his own land. So, we've come here today to dramatize a shameful condition.

NNAMDIMany of the issues marched for and protested in 1963 remain today. So, how will this year's march be similar and/or different to the one nearly 60 years ago? Welcome to "March on Washington 2020: The Commitment March." I'm Kojo Nnamdi. Let's begin. Joining us now Tiffany Dena Loftin is the National Director of the Youth and College Division of the NAACP. Tiffany, thank you so much for joining us.

TIFFANY DENA LOFTINThank you for having me.

NNAMDITylik McMillan is a policy advisor and the National Director of Youth and College at the National Action Network. Tylik, thank you for joining us.

TYLIK MCMILLANThanks for having me.

NNAMDIAnd Aaron Bryant is the Curator of Photography, Visual Culture and Contemporary History at the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture. Aaron, thank you for joining us.

AARON BRYANTThanks for having me, as well.

NNAMDIAaron Bryant, walk us through the historic March on Washington in 1963. Why was it needed, and how did it come together?

BRYANTWell, it's really interesting. Again, when we think about the 1963 march, folks about the jobs and freedom. And it was really focusing on not just social justice and social justice through civil rights, but social justice through economic rights and economic justice, as well. And so, you know, that's something that's sort of lost to history. But that's really part of King's background as a social gospel preacher, in many ways. And he had always thought about the idea of civil rights leading to a much larger human rights movement, and not just across the nation, but even globally. By the end of the 1950s, when King had traveled abroad, particularly to India and Africa, he comes back with a renewed sense of how his work really does need to focus on human rights issues that affect everyone around world.

BRYANTAnd so, central to that would be social justice through economic equality. And so, in many ways, the March on Washington would be a culmination of that. Working with people like the important architect, of course, Bayard Rustin, who really took a couple of months to put this really historic march together. It was really amazing when you think about how many other movements leading up to the 1963 march was, in many ways, sort of focused on localities, whether it's in Selma or Birmingham -- or even Chicago, to a certain degree -- where all across the country you had people working locally for civil rights. But King, you know, comes up with this idea of making it, you know, the civil rights movements into a national movement to bring together an entire nation to fight for human rights for everyone.

NNAMDIWell, the march I know had goals and objectives. What were they, and were they successful?

BRYANTWell, I would say yes, to a great degree. You know, we can say that the Voting Rights Act, for example, and Civil Rights Act follow, you know, within the next couple of years, because what the march helped show is King's ability to work with different organizations including unions and other civil rights organizations to bring together an entire nation of people. And so that becomes an important sign to policymakers in Washington, D.C., that this isn't just about boycotting buses. But there is something huge here that, you know, folks can come together to create a national movement. And so out of that comes other kinds of legislation. Again, you know, you have in '64 and '65 both civil and voting rights acts. And then I would say, you know, that's really important. Then, of course, we have the issue of economic rights. But one of the things that people don't realize, and this is something that when you're looking through some of the photographs of the march, and even in our collection, we have a protest sign from the 1963 march that says, "We demand an end to police brutality now."

BRYANTAnd so there's that strong connection that even during the '60s there was an issue that was being addressed across the nation.

NNAMDIIndeed, Tylik McMillan, the National Action Network is the lead organizer for this year's March on Washington. What do you have planned and how will this march be similar or not to the 1963 march?

MCMILLANYeah. Well, first and foremost, thank you for having me. And the historical aspect of the 1963 march to Washington as we're convening with Martin III in addition to Reverend Al Sharpton. So, honoring that historical aspect of it, but also taking what we have today as we understand as we, in this moment, also honoring the fact that we lost a civil rights icon of our time, John Lewis, who was always on the frontline of voting, in this moment during COVID-19 that we understand that the vote is under attack, when we understand that ballots and early voting is under attack, as we understand folks are having to choose between their health and the right to vote and governments don't want to fund our elections, governments are removing early voting polling sites -- as we look at this administration that is really marginalizing Black and brown communities away from the ballot.

MCMILLANSo, we understand that's under attack. So, getting in good trouble, necessary trouble in this moment. Also knowing as we understand Black and brown bodies are disposable to a system of police violence that was supposed to protect and serve. And so when we're looking at police accountability, the reason why we are working with the families, we think of the George Floyds and the Ahmaud Arberys, the Breonna Taylors, the Eric Garners, the Treyvon Martins. But also lifting up families that are right here in the District of Columbia, because we understand, yes, we hear about the cases that are headlined. But we also want to as we come to Washington D.C. to lift up issues that is happening right here in the city.

NNAMDIJeremy, you have a question that's really for Tylik.

JEREMY BERNFELDThis is a question from Victoria, from D.C. "This is such an important issue and march, but given COVID-19, how do we do this safely? I do plan on attending if I feel safe."

MCMILLANYeah. Safety being at the forefront of this march and the planning. We're working D.C. Mayor Bowser and D.C. Health Department. For folks who are traveling out of town -- as you may notice, the D.C. Mayor had put out a list of hotspot cities and states. And we're encouraging those in the states that are on that list to remain home and to join us virtually. We have satellite actions happening in South Carolina, in Florida and Texas. And literally, we have these satellite rallies happening throughout the country, to encourage folks to join that. We all have a virtual option as Tiffany is here, and the NAACP is hosting a virtual option for folks to attend. It will also be broadcasted in all major news outlets. We we're looking at CNN, MSNBC, BET. You can watch it right there in your home. So, we're encouraging folks to stay home. Now, at the march, everyone will be getting temperature checked. There will be a general entrance on 17th Street, where folks will get their temperature checked, issued a mask.

MCMILLANAnd sanitation stations, and in order to enter folks will get their temperature check and will be issued a mask. And from then they'll be given a wristband that identified that they've gotten their temperature checked. And we're breaking the Lincoln Memorial into grids. So, as folks are entering our volunteers and staff have an understanding of how many folks are in each grid, so the folks can properly social distance. And like I said, they'll sanitation stations throughout the Mall. And, like I said, safety is the main priority of this march and the reason why we're working so closely with the Department of Health and the mayor to ensure that we are taking all the precautions to ensure that everyone is safe.

NNAMDITiffany Dena Loftin, as Tylik said the NAACP decided to go the virtual route with this year's march. Tell us how your virtual march will work and what do you have planned?

LOFTINYeah. So, you can go to 2020march.com. We are an official partner, of course of the National Action Network in this year's commemoration for the annual march on Washington. We have a series of a few things. When we say virtual march, we want folks to remain safe and put their safety and their health first. And so, as Tylik had said, if there are folks who know that either they can't make the trip or it's not safe for them to be there, we will take care of you online. We want folks to join our event on Friday in the evening at 7:00 p.m., to join us for a series of conversations. Some of those conversations are going to be in a generational organization this conversation the last two months about young people in the streets and young people protesting. And what that means not only in the generations of organizing that has happened, but what that means in this moment for some of the means that have opted and uplifted, what it means, because right now I'm in Louisville, Kentucky organizing for justice for Breonna Taylor as I'm taking this call.

LOFTINAnd we want the folks who were actually involved in the work to also be a part of these conversations. And those conversations will happen virtually. We are also highlighting celebrities. We're going to have performances. We're going to have a lot of fun. We're going to celebrate our blackness. But we are going to also uplift the policies and the lawsuits the NAACP has done. We've partnered with the movement for Black Lives with their programming, which is happening subsequent to after ours. And we just want folks to participate in two things, I think: One, making sure that they are a part of the national agenda and conversation or what it means for justice for the Black community, and two, what it means to community build virtually in this moment of COVID-19. And so we're going to welcome folks. Again, that website is 2020march.com.

NNAMDIWho are some of the people who will be speaking at our virtual event?

LOFTINI don't want to tell you yet. You have to go to the website and check it out.

NNAMDIOkay. That makes sense. Jeremy, you have another comment.

BERNFELDThis one is from Carol-Anne, who says: It's my deepest regret that I did not attend the March on Washington in 1963. I was a New York City resident, and just because I feared the terrible traffic on 95 in a very old 1954 Chevy, I didn't attend.

NNAMDIThat is an expression of regret. Did the individual indicate she's coming this time?

BERNFELDI'm not sure.

NNAMDIWe can't be sure. I'd like to go to a clip of the Reverend Al Sharpton, the founder and president of the National Action Network. This clip is from George Floyd's memorial service in June.

REVEREND AL SHARPTONWe were smarter than the underfunded schools you put us in, but you had your knee on our neck. We could run corporations and not hustle in the street, but you had your knee on our neck. What happened to Floyd happens every day in this country in education, in health services and in every area of American life. It's time for us to stand up in George's name and say, "Get your knee off our necks."

NNAMDITylik, powerful words. Can we expect the focus on those issues from the march, and in particular from Reverend Sharpton Friday, racial disparities in education, in business and healthcare?

MCMILLANYes. Yes, exactly. As we understand that, and we're talking about Black issues, we understand that criminal justice isn't the only Black issue. We understand that it is healthcare that helps makes our communities safe. We understand that it is investment in childcare, investment in housing and food insecurity that happens in communities. It is the investment when it comes to education and ensuring that folks have access to attain wealth in this country. So, we understand that all those issues are what creates, you know, prosperity in the Black community. So, all those issues are issues. And as the reverend for far too long there has been putting knees on the necks of Blacks in this country. As we know, the reverend is a preacher and so he used that analogy. And we understand that in those moments, that hindered us as we have been coming up in this nation. We know that Black people have been disproportionately impacted in all of these areas and not just in the criminal justice aspect.

NNAMDISo are you going to be as coy as Tiffany is about who's going to be speaking at the event or will you tell us who some of the speakers will be?

MCMILLANYou'll have to wait and see. You'll have to wait see.

NNAMDIHave to wait and see.

LOFTINYou don't have to wait for the virtual march. You can just go to the website right now.

NNAMDIWe have a question about the '63 march. Go ahead, Jeremy.

BERNFELDWas A. Philip Randolph a major organizer in 1963, and how did they organize to prevent any violence?

NNAMDIAaron Bryant?

BRYANTYes, as a matter of fact. And, you know, looking at what the march was in many ways that was in alignment with the kind of marches that A. Philip Randolph actually imagined. Now, we have Bayard Rustin, who was really sort of like his deputy in many ways. And so he took on the logistics of say the day-to-day kind of operations in organizing. And so we often associate Bayard Rustin with the march. But, really, A. Philip Randolph is -- you can think of him as sort of the brain behind the idea. And it wasn't the first time. And even for both A. Philip Randolph and Bayard Rustin, you know, planning these kinds of marches and looking at issues related to human rights is something they have been doing -- and economic rights -- is something they have been doing, you know, for some time. Even two decades before the 1963 march.

NNAMDIAaron Bryant, what differences do you see between the protests and march in 1963 and the protests today and what we think Friday's march will focus on?

BRYANTWell, I think there are going to be some of the same issues. As Tylik had mentioned, you know, some of the economic-related issues, healthcare, job training and access to jobs. I mean, really what it all came down to was if America is really about freedom and democracy and equality, then each and every one of us should have equal access and opportunity to achieve the American dream and to have equal protection and the full rights of citizenship under the law and as outlined by the Constitution. And so, ultimately, I think that's an important parallel if we were to sort of wind all of this down. It's like it's all about the constitutionality of what it means to be an American, and we all should share in those rights and privileges. But I think that what we're dealing with today is not that different than what we were dealing with in the '60s. Again, thinking about the idea of protestors carrying signs saying, "Demand an end to police brutality," for example.

BRYANTRight after that, we're going to have uprisings and, you know, all kinds of uprisings that are happening in different parts of the country leading up to the late 1960s. And so I think that's really important to keep in mind. It's about citizenship, equal rights and protection, and the full benefits of citizenships. We all should have all of those privileges.

NNAMDIAnd, Jeremy, you have a question?

BERNFELDThis question is from Jennifer in Reston, Virginia. "Tylik, young people like yourself give me so much hope for our future. What gives you hope now, living in this pivotal time?"

MCMILLANAs I said all the time, what gives me hope is my little brothers and my sister. And first and foremost, seeing folks like Tiffany who are out in the streets every single day keeping the pressure. That's what gives me hope. For me, what I look at is I understand that, in this moment, this moment isn't just for myself. This moment isn't just for my mother or my brothers. This moment in history is a moment, as former Congressman Elijah Cummings would say, "for generations yet unborn." And I think when folks understand that aspect that we're not just in this moment for ourselves, but when our children's children and my children are looking in the history books, I want to them to say that their father stood on the right side of history. And I think folks should also think about that, where will you stand? When they're looking in the history books, will they say that you were standing on the right side of history? So, that's what gives me hope. When I think about those children that are yet unborn. And I understand that when this fight is over that I can say I did my best to ensure that they had a better future than what I had.

NNAMDISame question to you, Tiffany.

LOFTINWhat gives me hope is my unwavering love and support for Black people. The things that Aaron mentioned around what was fought for 57 years ago and the amount of unrest that has happened this year inspires me. We have folks who look like myself who are unafraid, who are courageous, who are taking risks, who are demanding for things that we didn't think were imaginable in this country. The conversation around defund the police, the conversation around canceling student loan debt, the conversation around accessible, affordable healthcare for everyone, the conversations around every woman's right to choose what they're going to do with their own body, the conversation around -- as Aaron mentioned -- immigration and making sure that folks have all the rights and dignity that they deserve in this country, the list goes on. I have a whole agenda for what this country looks like. And our young people are not only demanding it, but they're fighting for it.

LOFTINAnd Black folks, young Black folks of all the diaspora are at the frontlines of that demonstrations. And I know, similar with me -- been in this work for a really long together, I know that without a doubt that in community across the country and even globally folks are standing with us. And we know that the students who are -- some of them, some of my students are returning back to school are leading with that agenda. And that's what keeps me hopeful.

NNAMDIYou're echoing one of the cries from the late 1960s, early 1970s, which was undying love for Black people. You are essentially echoing that identical sentiment. Aaron Bryant, less than a year after the 1963 march, the Civil Rights Act was passed, you mentioned. A year later, the Voting Rights Act was passed, you mentioned. What are you hoping is accomplished in the days, months and years following these marches?

BRYANTOh, man. That's a long list. And I think, you know, Tiffany sort of had a hit on some of the starters. But I think there are issues, again, revisiting what does it mean to be a democracy and what are the promises of democracy. I would really encourage people to go back and read Martin Luther King's speech the "I Have a Dream" speech from the March on Washington because we end up missing so much. And what that speech was really about was, okay, well, you know, you have to put your money where your mouth is, basically. You know, it's one thing to talk about democracy, but what are we actually going to do to create equality to make sure that we all enjoy the same rights and protection of citizenship when we talk about democracy and what it means to be in America, as well as what it means to be an American. And so I think what I hope comes out of the March on Washington are conversations where we can all really begin to think about that.

BRYANTYou know, Frederick Douglass said during the 19th Century that power concedes nothing without a demand. And, again, going back to what Tiffany talked about with this March on Washington and any march, any movement, even recent protests this past summer, they're all about making people aware, making them alert that we are making a demand. And that's an important first step, is to, one, make the demand and then to have that demand recognized. And I think that's one of the important things that these movements this past summer as well as on the March on Washington give us. They give us the demand to be recognized, to be acknowledged and to be heard. And I think that's really an important first step.

NNAMDIBut I got to ask both Tylik and Tiffany, are there any specific policy changes that you are hoping will result from these demonstrations? First you, Tiffany.

LOFTINThe demonstration itself, no. And I'm going to be very honest. Our opportunity for this demonstration is to educate folks, is to bring folks in, is to make sure that folks are engaged in political homes. Let me explain what I mean by that. A political home is a place that you go where you can invest your talent, time and resources to build on those policies that you're asking me about. Those don't happen at the march just magically on Friday. And they won't move frankly in Congress just because we show up in D.C. on that Friday. What we need to do on Friday is demonstrate our power in numbers. What we need to do on Friday is demonstrate the new wave of leader who, you know, were awakened by what with Richard Brooks and Ahmaud Arbery and Breonna Taylor and George Floyd and welcome them into the movement, who want to get involved. And then after the march is to charge them into action. There are things like the Breathe Act that the Movement for Black Lives has launched. There are things like the loss of the NAACP has had now on the U.S. Postal Service and the grandmaster.

LOFTINThere are things like the cancelation on the student debt, which I named earlier. There are things like helping the Voting Rights Act because we want to fight back against this oppression that is happening locally and across the country. There's hundreds of policies that are taking place that are already happening that are not dependent on whether or not we show up. What we're trying to do on Friday is recruit people to the movement to help us advance that agenda. The Senate just left without voting on anything to support COVID-19 and the pandemic. We have schools that are reopening. There's a lot that needs to happen on the ground. And so what we're demonstrating again is how much we disagree with what Congress has done, how much we disagree with what the commander-in-chief has done, and what that agenda is. Like Aaron said, to state it clearly to the masses and recruit those folks in to join our organizations to fight for that change.

NNAMDITylik, I see you nodding in agreement. So, I'm not going to bother to ask you. No, I'm just kidding. Go ahead, give your response.

MCMILLANShe put it all in a nutshell, and I couldn't agree more. I think we charge folks to go back like she said to join the fight to get in the fight. But, from there, it does not end there. Folks have to go back to their communities and do the work, because we understand that it's at community levels and locally that we can see these changes come. So, she said it so beautifully. And, like, encouraging Congress to pass -- to restore the Voting Rights Act. They want to talk about -- the Senate wants to talk about how great of a leader John Lewis was, but yet the bill that he was so passionate about voting is still sitting while they return home and do nothing.

NNAMDIJeremy, we have another question?

BERNFELDWe have a couple of questions about this year's marches. So, first, "How are you including children in the march this year, virtually and at the march in person?" And then, also, "What metrics do you have in place to determine the success of the march? Is participation the only key measurement?"

NNAMDIFirst you this time, Tylik.

MCMILLANYeah. So, definitely getting young folks involved. I think just as a historical aspect, when we think about the civil rights movement, I think about my alma mater North Carolina NC State University where it was four young college freshmen that started this 1960 sit-in movement. I want to think about the Children's Crusade in 1963. When I think about all this stuff that young folks have been at the forefront, I think it's critical to have those conversations. But, I mean, for folks to come out, like I said we are having an in-person march, but I think it's critical after the fact of the march to continue to educate young folks and educate, you know, folks that politics in this movement isn't just the exception, but it becomes the new norm for folks, That, you know, they have a space at the table and young folks have space in these rooms. And, for me, that's the big part. I want folks to be able to have input on the decisions that are being made about them, but be aware of these issues and how we can educate them on what's happening. So, the education piece after the march is a really big piece for me with children and young folks.

NNAMDITiffany.

LOFTINI went to my first March on Washington. I think it might've been 2016. And I remember that time ran out, and some of my colleagues -- Philip Agnew and Sophia Campos, who were the youngest folks there -- didn't get a chance to speak. And so we did a two-minute virtual campaign that allowed young people to record themselves for two minutes, if they were at the march, what would they have said?

LOFTINAnd so we took that idea and implemented it for our virtual march ahead of time. Not waiting reactively, but doing it proactively. And so, I work at NAACP with black folks under the age of 25 years old, and we have young people who have recorded their two minutes that you all will get to see on Friday, who are part of a compilation of demands. Those things about what is it that they're experiencing, what do they want to see, what is the world that they imagine? What are some of the things for justice that they're fighting for and their education system and their schooling, especially during COVID-19.

LOFTINBut also how are they preparing to be future voters because a seven-year-old should be just as engaged as an 18-year-old when they're casting their ballot about what the Democracy in this country should be, and how civic engagement is necessary and important. And so what we're asking folks to do to measure our metrics is not only just to show up so we can count the views, because, you know, that's not really going to help move the country to change the world. But what will is if those viewers volunteer at the NAACP to be civic engagement organizers in their community.

LOFTINWhat we're asking folks to do is to volunteer and to sign up to be a volunteer on our website, so that we can engage them in not only doing virtual text messages, virtual phone calls, virtual phone banks, but virtual walks, as well, to educate people about the elections. We're partnering with Vote.org and Politicking, the app, so that folks have their digital voter guide. And we want to make sure that people make the best educated decisions.

LOFTINWe have a lot of time. I think -- well, not that much time left now, but I think we're at 50 days until national voter registration day, which is September 21st, and then November 3rd. And we want to make sure that the folks that are helping us across the country prepare their own circles and communities, because we can't go outside, and we can't stand on the corner. We can't stand in front of the grocery store. It's unsafe.

LOFTINWhat we want people to do right now is make sure that your families, your jobs, your cousins and them, the people at your school, the people, you know, down your neighborhood and down the block, that you're doing the work of a leader to make sure that your community and your neighborhood are educated and supported in their decisions to cast their ballot on November 3rd.

NNAMDIJeremy, someone has a question for Aaron Bryant.

BERNFELDYes. The march is happening on the National Mall. Is the National Museum of African-American History and Culture observing the march in any way?

BRYANTYes, as a matter of fact. Before I move on, though, I wanted to get back to what Tiffany was talking about. What's really important there is this whole idea that you can engage in many ways, and engage in your communities in many ways. You know, being a part of resistance or making social change isn't really just about participating in a march and carrying, you know, protest signs. Sometimes it's just about providing water to a group of volunteers who are actually going out and helping people to register, bringing them, you know, a case of bottled water.

BRYANTSo, there are many different ways that we can engage in our communities. And I think that's what's important about marches, because -- and movements, is because they create this sense of community that we can all belong to and we can all do our part. And along those lines, I guess this is sort of a segue, yes, the museum is doing its part, as well. As a matter of fact, we're working on a website specifically to recognize the 1963 March on Washington. But we're looking specifically at the role that marchers have played historically up until present day, looking at the Black Lives Matter movement. And what are some of the things that these marches have in common?

BRYANTAnd part of that is, you know, the sense of solidarity and community. That's really important, that you're not suffering alone. You're not fighting alone, but there's a community of people across the country and even around the world that is part of the same movement and change that you're trying to create. I mean, our entire museum is about 400 years of why black lives matter. (laugh) So, I would say that, yes, we're doing it on that day and the other 364 days of the year, in perpetuity.

NNAMDIAaron, Observe has estimated that 75 to 80 percent of the marches in 1963 were black. We've been seeing a slightly different picture with some of the marches that have been taking place lately. Do you believe those numbers are likely to be different for this year's march?

BRYANTThere's no telling. Actually, I was really surprised and pleasantly surprised, for example, with the George Floyd protest that's been happening over the summer. CNN, for example, did a photo essay where they looked at protests happening all over the world. And I was just really struck by how, in every single corner of the world, there were groups of people coming together to protest holding up signs saying black lives matter.

BRYANTYou had Aborigines and indigenous tribal there, you know, protesting Black Lives Matter, Portugal, Brazil, Switzerland. I mean, literally every corner of the world you had people protesting and holding up signs that said black lives matter. So, it could be extremely different in that you have people all over the world who are part of this larger movement now.

NNAMDIJeremy, you have a question to go to the entire group?

BERNFELDThis question is from Cheryl. In the '60s, there was a national leader in the person of Martin Luther King, Jr.. Is there a need today for a national leader or do you see a different approach in advancing the agenda and fight for change?

NNAMDII can answer that. No, (laugh) but I'll let Tiffany answer it.

LOFTINYeah, I was about to jump in before you started talking. So, no, there is not a need for a national leader. What we -- what we're operating off of is that there are leaders across the country that are decentralized, that are a part of different movement groups, that are a part of different demographics, different ages, different sexual orientations, different religions.

LOFTINOur folks are operating not leader-less, but leader-full, right. And we have people across the country in NAACP and college division that are leaders of their own chapters that are passing hate crime bills, that are passing Breonna's Law here in Kentucky, that are passing legislation that says that we're going to increase funding for our higher education and education in general.

LOFTINThose are folks that sometimes go nameless because they don't have as many social media followers or they don't get an opportunity to sit on a panel like this or they might not be on CNN. But very much so in their community, those are the leaders. And those folks are also artists. Those folks are also educators. Those folks are also parents.

LOFTINAnd so, at least from my perspective, where I sit, because fortunately I have the blessing of doing this work full time and this is my job, I know who those leaders are. The folks like D'Aungillique Jackson at Fresno State University or Jaida Hanson who was arrested on the lawn of the district attorney here, Daniel Cameron in Kentucky to fight for Breonna Taylor. She was just arrested, and she's 23 years old.

LOFTINWe have Leslie Redmond who's a leader in Missouri who was fighting for George Floyd. And we have Major Woodall who's a leader for the state conference and NAACP in Georgia, who not only has been fundraising for a national coalition, but is also put to the charge to pass a hate crime bill after Ahmaud Arbery was murdered.

LOFTINAnd so these names that I'm naming are folks that y'all might not know just because you might not be in the small circle that I'm in, but that doesn't mean that we don't have leaders across the country. And although we have the blessing, the blessing of learning from our elders, the folks who have the wisdom, my mentor, Cortland Cox, who's part of the Nonviolent Action Coordinating Committee and was a SNCC veteran are those folks that we honor and that we work with.

LOFTINBut there are leaders all across this country that I could name, and I'd be here too long for the interview to allow y'all to hear the names of people that I know. So, y'all should definitely check those folks out. And, no, we don't need one spokesperson. We got plenty of them.

NNAMDICortland Cox was one of my mentors, too. Tylik, same question to you.

LOFTINLook at that.

MCMILLANYeah, just honoring the fact that there's leaders in our community that do the work and see the work firsthand, those are leaders. As Tiffany said, we have the honor to learn from our elders and folks who were in this fight before us to learn from. I learned so much from my mentor, Reverend Sharpton, but I understand that not only is he someone that we learn from, in general, but there's community leaders that are at the local level that's doing great work that you may not hear about. So, we honor their work that they do, as well, but we also honor the work that leaders like my boss does who's been in this fight for a while. So, I honor that aspect, as well.

NNAMDIAaron, five years after the March on Washington and a month after Dr. King was assassinated, another march took place, the Poor People's March. Describe the state of America and the civil rights movement in the spring of 1968 and why that march was needed.

BRYANTOh, wow, yeah. That was actually my dissertation topic, so I'm trying to figure out if I can condense it...

NNAMDI(overlapping) In 60 seconds or less, yes. (laugh)

BRYANT(laugh) Okay. Well, I would say it was something similar. I'm going to take it back to the long, hot summer of 1967, when all across the country, there were 150 to 160 uprisings happening. And King was still alive. And, in many ways, his poor people's campaign would do two things. One, it would be sort of like a 5th anniversary recognition of the 1963 March on Washington. And it would be more specific in its demands for economic justice and social justice.

BRYANTBut also, you know, you had talked about earlier the language of the unheard, and how uprisings that were happening all over the country had to be responded to. And so, this march, the poor people's campaign, would be a way to channel the frustrations that poor people and Black people all across the country were feeling. He wanted to find a way to channel that and bring that directly to Washington, those grievances to Washington.

BRYANTAnd so that's how I would position the poor people's campaign. I would say, however, it wasn't just a march for one day. It was actually six weeks. People packed up their entire lives and moved to live in the National Mall for six weeks. And when you read some of the stories, people left their homes knowing good and well they could never return back again.

BRYANTWhen I talk to some of the folks who were a part of that movement, you know, they talked about how, you know, folks got on buses to make their way to Washington. And they looked back -- they looked out the window to look back at their homes and they could see in the distance homes being set on fire, which is absolutely amazing. So, they knew they couldn't return back again. They gave up a lot to be a part of that march.

BRYANTAnd so when we think about what people had to sacrifice then for the poor people's campaign, you know, think about, well, what can we do today to make sure that that dream and that vision for economic justice didn't die.

NNAMDITylik, before I let you go, if people want to participate in Friday's march, where do they go for more information and to register?

MCMILLANYou can go to ww.nationalactionnetwork.net, or you can -- those other ways, check there. Or you can follow us on social media, where all information is being posted, as well.

NNAMDIWell, Tiffany, you mentioned yours already, but do it again.

LOFTIN2020march.com, super simple.

NNAMDITiffany Dena Loftin, thank you so much for joining us.

LOFTINThank you for having me.

NNAMDITylik McMillan, thank you for joining us.

MCMILLANThank you for having me. It's an honor.

NNAMDIAnd Aaron Bryant, thank you for joining us.

BRYANTYeah, yeah, thank you, Kojo. Anytime.

NNAMDIYou know, we've spoken a lot about the 1963 March on Washington, so let's talk with someone who help organize it. Joining us now is Congresswoman Eleanor Holmes Norton, now in her 15th term representing the District of Columbia. And Congresswoman Eleanor Holmes Norton, as you should know, was a member of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. Congresswoman Norton, thank you so much for joining us.

ELEANOR HOLMES NORTONI'm here, and I've been listening to much of what's been said.

NNAMDIAs a young civil rights leader and activist, you helped organize that 1963 march. How did you get involved and what was your role?

NORTONI must tell you, I was in Mississippi with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, where we were attempting to open up the Delta region. That was the last great part of the South that had not been organized by the civil rights movement, when I got a call from New York. And remember, I'm a native Washingtonian, but I got a call from friends in New York, saying, it's going to happen. Do you want to come and work for the March on Washington?

NORTONNow, understand, when you were a SNCC student, I was in law school at the time, you obviously are not being paid. But they said, you can actually be paid if you come to New York (laugh) to help organize the March on Washington. I thought that was an opportunity of a lifetime. And I hopped a plane, went up to that brownstone in Harlem where the March on Washington was organized.

NNAMDIWere there a lot of women involved in organizing that '63 march? Publically, it certainly looked -- appeared as if it was led by men.

NORTONThere were. There was a controversy, because the so-called big six included Dorothy Height, the chair of the National Council of Negro Women. Now, five of them spoke. She didn't get to speak. That shows you that, at that time, feminism was not even in its infancy. And there wasn't even any big hullabaloo, but there should've been. There were speeches, there was a crowd that we were not sure was coming.

NNAMDIYou grew up in a segregated Washington. How did that prepare you for your own role and fight for civil rights?

NORTONGrowing up in segregated D.C., going to segregated public schools, Brown vs. Board of Education was decided just as I was leaving public schools. I had an advantage. This was up South. What it meant was that African-Americans here were very conscious, including my own parents, and were not accepting of segregation. We were very different from, for example, black people in Virginia, right across the line, or even Maryland. It was a very conscious and often college-educated black citizenry.

NORTONThe reason I say college-educated is not because of my own parents but, Kojo, if you look at the kind of employment we have here today, that's the kind of employment we've always had. If you didn't have some high school and preferably some college education, you could not get a job in this white-collared town. So, that meant that you had a lot of emphasis put on education and that included the kind of education that made us a very conscious city here in the black community, socially conscious.

NNAMDIThe March on Washington was 57 years ago. Obviously, a lot was accomplished but what remains to be done?

NORTONI really think it's very important to focus in on goals. And that's where Bayard Rustin played such an important role. You can't just march for -- in protest any longer, not if you come to Washington. In Washington, you will find the President of the United States, the House and the Senate. So, if you come here, those entities expect that you must want something from them.

NORTONThe 1963 march was very clear what its aims were and very clear what its outcome ultimately was. It was first called, I think you mentioned this, the March for Freedom. Bayard made sure it was the march for jobs and freedom to make sure black people's place in the economy was front and center, as well. But look what that march produced. Because pending were the Civil Rights Acts, essentially, what the march did was to demand that those acts be passed. And out of that march, it is clear, came the 1964 Civil Rights Act and the 1965 Voting Rights Act.

NORTONNow, this march needs to focus itself, as well. And here I speak now as a member of Congress, so I'm always focused on what can we get out of all these people coming here. And so I'm focusing on a hope that the march will emphasize the George Floyd Justice in Policing Act. That is an act we passed and the House is pending in the Senate. It needs a march to keep it going. So if people are coming here on the 28th, we welcome them. We can't wait to see them. I certainly hope that they focus on pending legislation, because that's what we do here in the nation's capitol.

NNAMDIWill you be participating in this year's march?

NORTONI'm going to try my best, socially distanced. I was actually on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, where I could see that this was a successful march, because I work for the march. Now, this time, I don't know how we're going to pull it off. And people are trying very hard. I hope there are a lot of cars marching. That would be a good place -- way to do it, have cars come up. And I think they're trying their best to socially distance.

NORTONThe mayor has indicated, the mayor of the District of Columbia has indicated that if you're from a hotspot, don't even come to the march. So, we're in the middle of a pandemic, trying to focus a march. And I certainly hope that many people who will not be able to get to Washington will follow this march on the many sites and online, which may be the best way to pull off a successful march today, in the middle of a pandemic.

NNAMDIDid you expect anything like the current protests that we're seeing around the country? What do you feel are the strengths of this current movement?

NORTONThis is an outgrowth, really. I like to think of it as an outgrowth of the '63 March on Washington, that people came to understand, then, that if you want to get something done in Washington -- that is legislatively, or by the present -- you have to come to Washington. And so I think the people who come are focused on getting the attention of Congress to getting something done.

NORTONNow, the George Floyd Justice in Policing Act is what is pending, what has gotten through the House, what is pending in the Senate. And I certainly hope this march focuses on that, because I think it could drive that pending legislation the same way our march drove the 1964 Civil Rights Act and the 1965 Voting Rights Act.

NNAMDIYou mentioned Bayard Rustin, one of the key organizers of the march. And I had mentioned earlier in the broadcast that one of my mentors when I came here was Cortland Cox, because just about all of my mentors were former SNCC members at the time. And they talked about Bayard Rustin all the time, even though many people in the general public did not know who he was. Tell us a little bit about what was Bayard Rustin like, and what was it like working with him?

NORTONWell, he mentored many young people. Cortland Cox was one, and I certainly was one. Bayard Rustin was -- I don't use this word lightly -- a genius. I don't believe that there was anybody else who could've organized this march. It had no precedent. So, how do you organize a march when there's never been a march? And certainly not a mass march.

NORTONBecause his own life experience, thinking through social issues and thinking logistically, essentially, this was a one-man show in terms of how he got organized. He would say to people like me, and my job was to help bring buses and trains to D.C. Somebody had to parcel that off. Somebody had to decide how you get people to D.C. It was 100 different tasks like that that Rustin himself imparted to us. And that resulted in a masterful piece of organization, without precedent, that pulled off a march. And every march since has patterned itself on that March.

NORTONI can tell you that standing on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial where 250,000 people came as far as the eye could see past the monument, as far as the eye could see down the Mall, there were people. And so the success came in part because people knew what they wanted to accomplish, and because of the way in which Rustin led in organizing the march itself.

NNAMDINevertheless, on the evening before the march, the morning of the march, you and other organizers were pretty nervous about how many people would show up. Were you ultimately surprised at how many people showed up?

NORTON(laugh) I was nervous enough so that when volunteers were asked to be the last to leave that brownstone where we organized the march, I raised my hand, because I knew D.C. And I knew -- and that I would necessarily have to come on a plane. Everybody else came on a bus or on the train. And I knew if I came on a plane, I could look out the window to see if we were being successful at this, and that was the forethought. To be sure, as that plane neared Washington, there were people as far as the eye could see. And I knew right then that the march was going to be a success.

NNAMDIYou know, my SNCC friends used to say that planes weren't actually invented until 1965. (laugh) So, the fact that you got to ride on a plane in 1963 was a big deal. In a previous town hall, we discussed the racial disparities in the pandemic and in D.C., where African-Americans are 44 percent of the population. Black people represent 75 percent of COVID deaths. How has this happened and what is the plan if the virus continues to spread and end lives?

NORTONThe disproportionate rate among people of color I think comes from the kinds of jobs they do. We've been all told to stay at home. I'm teleworking. I'm talking to you from my home. But the essential workers who disproportionately turn out to be black and brown are out there doing their jobs. They are out there delivering the mail. We just had a big hearing on that. They're out there delivering the food. So, they are exposed in a way that white collar workers are not.

NNAMDIYou know, you just mentioned delivering the mail. Before I let you go, I do have to talk politics. Are you concerned with how voting will go on November 3rd here in D.C. and across the country?

NORTONKojo, I'm so concerned, because I've seen, in the primaries, how difficult it was for voting by mail to be done during a pandemic the way it's usually done. I am so concerned that I am asking my constituents to vote early, in person. I voted not even that early, a few days before my own primary. I went in there, and there was hardly anybody there. So, if people use early voting, they know their vote will be counted. And I hope that, all over the country, that's what people will do so we don't have the kind of pandemonium we had in New York and in other places around the country.

NNAMDICongresswoman Norton, always a pleasure. Thank you so much for joining us.

NORTONThank you for doing this tonight.

NNAMDIWe've heard a lot tonight about the 1963 March on Washington for jobs and freedom and what this year's Commitment March will focus on and be like during these pandemic times. So, thank you all for showing up and participating. I'm Kojo Nnamdi.

On this last episode, we look back on 23 years of joyous, difficult and always informative conversation.

Kojo talks with author Briana Thomas about her book “Black Broadway In Washington D.C.,” and the District’s rich Black history.

Poet, essayist and editor Kevin Young is the second director of the Smithsonian's National Museum of African American History and Culture. He joins Kojo to talk about his vision for the museum and how it can help us make sense of this moment in history.

Ms. Woodruff joins us to talk about her successful career in broadcasting, how the field of journalism has changed over the decades and why she chose to make D.C. home.