Saying Goodbye To The Kojo Nnamdi Show

On this last episode, we look back on 23 years of joyous, difficult and always informative conversation.

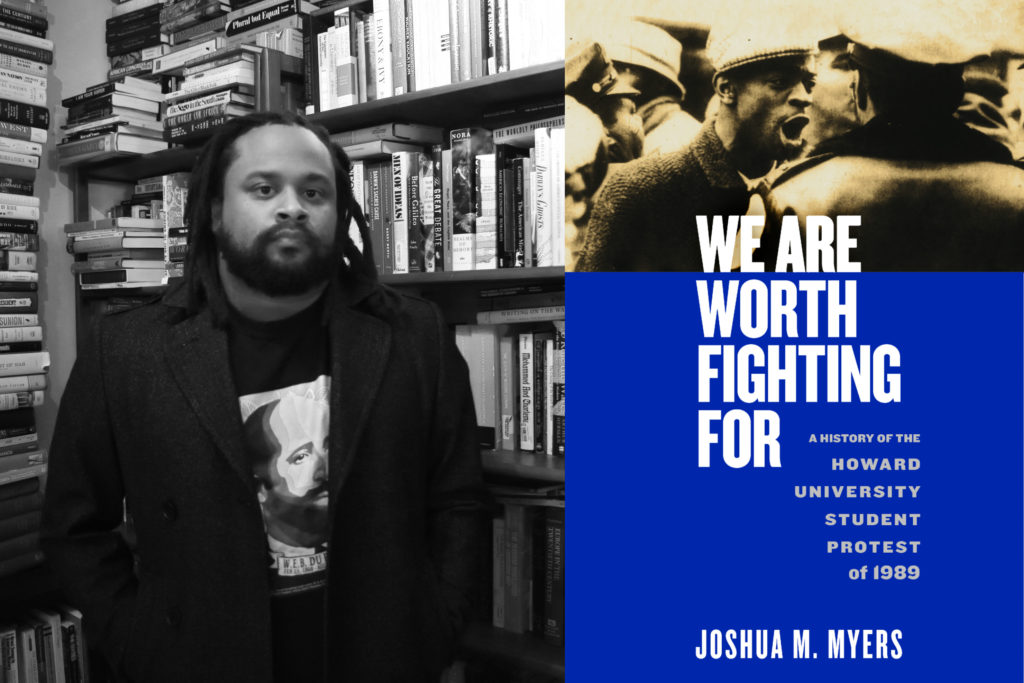

Twenty years after the 1989 Howard University protest, Joshua Myers collaborated with the protest's organizers to write recount its history in "We Are Worth Fighting For."

“The student protest of 1989 was, above all, a feeling.”

Joshua Myers recounts the three-day occupation of a Howard University administrative building with hour-by-hour detail in his new book, “We Are Worth Fighting For.” Among the students’ demands were a more Afro-centric curriculum; striking out tuition increases; creating a community service requirement to better connect Howard students with the larger D.C. community; and removing Republican strategist Lee Atwater from the Board of Trustees. With these demands, student protesters were trying to shape the future of Howard.

Myers also weaves in larger historical contexts that drove — and continue to drive — black student activism. In the eighties, national politics were shifting right, and students felt that acutely on campus with Atwater’s appointment to the Board. Hip hop was on the rise, and the music and culture created a space for new political sensibilities. (As Myers writes, “Hip hop became a powerful medium to express not only discontent but to imagine otherwise and to live it now.”) Black Nia F.O.R.C.E., the student organization that led the protest, was born out of a “genealogy of activism” that largely pulled on the well-documented 1968 Howard University protests.

We talk with Myers about his history, black youth activism and the central question that drove the protesters, which is still relevant today: What is a Black university?

Produced by Cydney Grannan

KOJO NNAMDIHip-hop, Reaganism and the tradition of black youth activism: these are the influences and conditions that contributed to students at Howard University protesting their administration in 1989. A list of seven demands from students left unanswered led to with three-day occupation of a university building, a siege from a SWAT team, and ultimately a change in the leadership of the university.

KOJO NNAMDIJoining me to talk about the protests that he writes about in his latest book is Joshua Myers. He's an assistant professor in the department of Afro-American studies at Howard University and the author of the book "We Are Worth Fighting For: A History of the Howard University Student Protest of 1989." Joshua Myers, thank you for joining us.

JOSHUA MYERSThank you, brother. It's a pleasure to be here.

NNAMDIWhy did you decide to write a book about these protests?

MYERSThese protests are really important to me. I am a product, in many ways, of teachers who were part of this generation. And, as a student government leader in 2008, two of the leaders of this protest came back to address us. And they talked about what it was like to be involved in this work of bridging student activism and student governance, and what we should do with these positions that we occupy. And so it's always been with me.

MYERSAnd then, when I was a graduate student, I connected with many other people who were involved in the protest. And, just a few years later, they asked me to tell their story. And that's how this collaboration between myself and the students who are involved in the occupation, that's how it flowered. And the result is this book.

NNAMDIYou talked about two of the leaders of the student movement. On the cover of this book, there's a photograph of a young man apparently yelling at a uniformed officer. Having been at Howard University in 1989, I think I recognize that young man as the individual who is now the mayor of Newark, New Jersey. Am I correct?

MYERSYes, that is. That's Ras Baraka.

NNAMDI(laugh) Yes. He was one of the two leaders of that student protest. The other, of course, we'll talk about a little more later, April Silver. This is the first book written on Howard University's protest in 1989. A lot of focus had previously been given to the 1968 protests, most notably as part of the series "Eyes on the Prize." Why do you think that is and what's the relationship there?

MYERSWell, there's a sense of the '60s as this heroic era, and, in many ways, it is. There were many heroes in that particular period, and it has generated a lot of attention because of that. And we have a way in which we talk about the '60s as a period that gave us access, you know, to American citizenship, that sort of solidified the notion of black power and self-determination and Pan-Africanism. And those things were happening in the 1960s.

MYERSBut they were also happening in the 1970s and the 1980s. Indeed, they're happening right now. And so, this particular story kind of gets lost in the gap in terms of people's wanting to talk about the urgent college and higher education issues today, and as well as the heroic past of the 1960s. We kind of miss the links in the chains when we only talk about, you know, these two extremes.

MYERSAnd so this is a book that I think will help us see that, you know, the continuity of the black struggle of even the 1920s and '30s, at HBCUs in the 1960s -- of course, that we know about -- and then in the 1980s, was secured by these students' action. And I think that continuity continues today.

NNAMDIJoshua Myers, the protests were a three-day occupation of Howard University's administration, building called the A building. What sparked the occupation?

MYERSWell, students were upset, because on February the 1st, or somewhere around that date, the university had decided to appoint Lee Atwater to the Board of Trustees. Atwater, at the time, was the Republican National Committee chairman, but he was known as a hired gun to sort of solidify these Republican campaigns. And he was known to use whatever means to garner that support. In 1988, he used the image of William Horton, who was a convicted -- a lifer, who was serving a life sentence. And he was on furlough, and committed another crime. And they used his image to sort of spark fear that the Democrats were not hard on crime.

MYERSIn any case, they used the image, and that sort of sent a racist message to, quote-unquote, "middle America," that this would happen if you elect Michael Dukakis as president. And that's what allowed George H.W. Bush to win the presidency that year. And the following -- in the ensuing months, Howard University decided that this particular figure would be someone that we should allow to be on our Board of Trustees.

MYERSAnd it didn't go over well with students, and neither did it go over well with faculty and alumni. But the students felt that they had a very particular ownership of the university, that they decided that it was necessary to force that meaning onto the administration.

NNAMDIBut it wasn't just Lee Atwater's removal from the board that the students were seeking. What other demands did they have?

MYERSYeah, and so they attached the selection of Lee Atwater to a series of other demands, and they connected them. So, you have the sense that, if a university has enough of a impetus to select Lee Atwater, then it also is redolent of a university that doesn't necessarily see African-American studies as a discipline that should be supported with, you know, more faculty and a center for the study of Africana, a graduate program, these kinds of things. And so they attached those demands together. They called for an Afro-centric curriculum for the entire university, in fact.

MYERSThey also looked at the sort of quality-of-life issues, right, the status of the dormitories, the surrounding community, the connection that students should have with the surrounding community. It's not an antagonistic one, but one of camaraderie, right. They looked at the issue of financial aid, one of the big issues during this period, because you know that, black students, they came from communities that were hit hard by the Reagan economic policies, and so financial aid was a big issue.

MYERSAnd so far as that was connected to Lee Atwater's ascent, they could make those connections and convergences in their demands. And so you have these quality-of-life issues, you have the curricula issues that are connected to the issues of Lee Atwater's appointment.

NNAMDIWe're talking with Joshua Myers. He's author of the book "We Are Worth Fighting For: A History of the Howard University Student Protest of 1989." He currently teaches at Howard as an assistant professor in the Department of Afro-American studies. Here is Fahima in Washington, D.C. Fahima, you're on the air. Go ahead, please.

FAHIMAYes. Good morning or afternoon, Kojo. I was an undergraduate with your son at Howard. And I also was part of the protest in the '90s, where we were trying to prevent Howard from becoming a gated community. That was also the protest there that Chadwick Boseman was part of.

FAHIMAAnd my question to the caller, I also am a member of alumni with support of HBCU students, and I wanted to know, did you have a conversation with any of the HBCU students because they very much look to the history and their elders. In fact, Ras and April Silver had a chance to meet with him. And we had a panel at Bus Boys and Poets with all three generations, those from the '68 protest, the '89 protest, and the current -- well, at the time, the protest that took place last year. And I'll hang up and take your answer.

NNAMDIWell, I can tell you, Fahima, Joshua Myers has done very diligent research on this book, and it essentially connects all of those protests. But I'll let him answer for himself.

MYERSThank you. So, yeah, we had conversations with those students. And our concern was, of course, ensuring that they were safe. And, to that end, we made those connections, and we made critical interventions when those interventions were necessary. And it was very clear that, you know, the students had a view of the university that was pretty much in line with previous iterations of Howard University student resistance.

MYERSAnd it boiled down to, to what extent should students have a say, to what extent should the black university reflect how students see it? And I think that was pretty much constant, when it comes to these particular actions. And, again, I mean, this goes back to at least the 1920s. Probably before that, we've had, you know, students assert themselves in a particular way.

NNAMDIAt the center of the protest is an organization that was called Black Nia F.O.R.C.E. Some of the key figures in Black Nia are people we may know today, like the aforementioned Ras Baraka, the mayor of Newark, New Jersey. Black Nia actually helped launch his political career. How was he involved in Black Nia, and how did Black Nia help him launch his political career?

MYERSYou know, that was an interesting conversation, when we think about, you know, the history, particularly of black nationalism in this country. I just wrote a blog from the Square website, which is NYU Press's site, which tells the story of where Black Nia F.O.R.C.E. came from. But, essentially, the easiest way to answer it is that it is the hip-hop generation's answer to Black Nationalist tradition.

MYERSAnd so they took the energy of hip-hop and they translated it into political organization. And everything that you would expect from hip-hop and everything that you would expect from the tradition of black nationalism was crystallized into this one organization. And Ras Baraka, along with his comrades, Carlisle Sealy, Chuck Webb and many people who would go on to participate in this protest, but also go on to participate in the education fields, go on to participate in the music industry, who would go on to do really important things politically were part of this formation, which was founded in January of 1988 at Howard University by Ras Baraka and his friends.

NNAMDIWhen I first came to Washington way back in 1969, it was to join a Pan Africanist organization. So, I'm intimately familiar with Ras Baraka's father, Amiri Baraka, who was, in those days, a part of that movement which influenced Black Nia F.O.R.C.E., along with a number of other ideological trends. But another key member of Black Nia was April Silver. Tell us about her role within the organization.

MYERSApril Silver's role is actually very important. She is really the person who gave me the title for this book, "We Are Worth Fighting For." It comes from her words. So, she is New York born and bred. She ends up going to California, and she comes back to the East Coast, and she finds that the people she resonates most closely with are the students from this particular area, the East Coast area. And Ras's crew is part of that general energy, and so she gravitates towards them.

MYERSAnd then, of course, she meets Morani Sanchez, and Morani Sanchez is the son of Sonia Sanchez. And she meets Sonia, and they start to have a lot of conversations. And, eventually, she brings Sonia down to campus regularly, and they would have these reading circles. And when Black Nia F.O.R.C.E. was founded, it represented the same kind of thrust and energy that she had been sort of pursing with Sonia Sanchez.

MYERSAnd so she joins, with gusto, and she decides to use her resources and her time to support the work of Black Nia F.O.R.C.E., but she was very quiet. And now, someone who is very quiet, many of the other members didn't know what role she was playing in the background, but Ras noticed. And, at a certain point, Ras stepped down from the organization, and he nominates April Silver to succeed him. And a lot of people are shocked. They're surprised. Why would, you know, he nominate April Silver, because many of them had associated the organization with Ras.

MYERSBut April Silver proved to be the right person for the job. And I think she had this calm energy that allowed her to have an impact in a way that Ras, who was very charismatic, probably would not have. And I think it was absolutely the right choice, but it showed that, even in this period, that Black Nationalist organizations did not see this notion of a gender hierarchy as a barrier. They knew that women had to play a role.

NNAMDIWell, April Silver was a part of my own small peripheral role in this protest. I was hosting a television show at Howard University at the time called "Evening Exchange," and we decided to have a conversation about the protest. And April Silver was the first guest we had. However, we added the chair of the faculty senate who, up until that point, had been fairly neutral but came out strongly in support of the students.

NNAMDIAnd we invited a member of the Board of Trustees who we assumed would be in support of the president. It turned out that that member of the Board of Trustees was also forcefully in favor of the students. She later went on to become mayor of the District of Columbia. But after that show was over with April Silver and the chair of the faculty senate and the member of the Board of Trustees, I got a phone call in my dressing room from President James Cheek, the president of the university, who then harangued me for about 90 minutes in defense of his own position, and in denunciation of the member of the Board of Trustees who had come out in support of the students at that point. That was, for me, being an employee of the university, fairly traumatic, even though he claimed several times during the course of the conversation that if I ever repeated the conversation then, he would fire me. But that was a long time ago.

MYERSWow. See, that's a new thing, that's a new history for me. Wow. (laugh)

NNAMDIWell, throughout the book, you remind us that Howard University student activists are trying to answer a larger question: what is a black university? Why was that, and is it still a driving force for the students?

MYERSAbsolutely. I think that was the question in 2018, as well. And so, this conversation about a black university was articulated directly, even though it was always a question, but it was articulated as directly in 1968. And so there's this conversation after the '68 protests in November, called “Toward a Black University,” where you have the students bringing in all of these different intellectuals, activists and artists to really come together and say, okay, we have this space. There are black people in this space. What are we going to do about it, given what's happening in the world around us?

MYERSThat question was raised in a particular way that the university system, as it exited, had no space for it, had no space to resolve. And so, for them, the black university was a place where you could answer those questions. What are we here for? What should we do? When should we study? How should we study? How shall we relate to the community and the world around us?

MYERSAnd to the extent that black universities to follow Du Bois's declaration in 1933, when he writes “The Field and Function of the American Negro College,” to the extent that black universities don't reflect black history, don't reflect black sociology, don't reflect black education, we have a problem. And that problem creates the tensions that we see with these protests.

NNAMDIHip-hop was becoming popular, or was popular in the '80s, but then you talk about how the music and culture surrounding it created a space for new political sensibilities. How so?

MYERSYeah. Again, this is something that I talk about in the blog that came out today, is that this new space was a space of attitude, energy, brashness. It was an in-your-face kind of music, which meant that we were not going to back down anymore. Right? And it's important, because it comes out of the sort of energy of the black communities that were ravaged by the economic policies of Ronald Reagan. It connects to the antiapartheid struggle, which I know you were a part of.

MYERSAnd these young people, they see the young people in South Africa, they see their lives, right, in places like New York and places like Philadelphia and here in D.C., and they say, it's time for us to stand up. And he put that energy directly into a form, called hip-hop, that could be spread. And that created the energy around a lot of the organizing that came in the first few years after the '89 protests, but certainly, the '89 protest itself, right. And so, hip-hop had a sort of consciousness about it that was conducive to political organizing, and I think that's the story that has yet to be fully told.

NNAMDITalk about the role Marion Berry, the then-mayor of Washington, played in all of this.

MYERSYeah, Marion Berry, who was mayor at the time, he was, of course, a veteran of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. And, as the story goes, when the police decided to execute the injunction to remove the students from the protest, he didn't know about it. He was not notified. Somehow, the chain of command excluded him. And there's a figure by the name of Kemry Hughes, who was the deputy mayor of youth services at the time, who had made a connection with the students. And he knew what was about to happen, so he went to Mayor Berry, and said, Mayor Berry, this is the situation.

MYERSAnd, as the police came into the building on Tuesday of the protest, the mayor shows up, and he orders the police to stop. And, to the students, it was a life-saving action, that they felt that this was it for them, had the police been able to fully breach the building. And Marion Berry shows up, and he calls the police off. And he stays in this building with the students after he did that to help them negotiate with the administration. And so he plays a very, very prominent role, in fact, one of the key roles of anybody in the protest.

NNAMDIAnd I can tell you, Kemry Hughes, he is still around and active in Washington today. But we only have about a minute or so left. What would you like your students at Howard to take away from these 1989 protests? What would you like, in fact, the public to understand?

MYERSI want them to understand that, you know, there are errors that we can talk about in history, but history is continuous. So, there's an energy, there's a spirit -- the word that April Silver used -- of the 1980s that we have to understand in order to understand ourselves. And so, to be a Howard student in 2020 is to be able to connect to the things that happened in the immediate past, but also in the long past. And '89 is part of that spirit.

MYERSI've got to close with a quote from Kelly Miller, the Greek mathematician and sociology's former dean of the College of Arts and Sciences. He says, “Those who feel it, know.” And he's talking about the Howard spirit. And I think part of that knowing, we have to continuously cultivate that. We have to continuously talk about the traditions in the past and the legacies that animate this space, because they all determine our identity. They tell us who we are, and so students should know that.

NNAMDIThank you very much. Joshua Myers is an assistant professor in the department of Afro-American studies at Howard and the author of "We Are Worth Fighting For: A History of the Howard University Student Protest of 1989." Joshua Myers, thank you so much for joining us, and good luck to you.

MYERSThank you for having me.

NNAMDIThis segment on the 1989 Howard University protest was produced by Cydney Grannan, and our conversation about the census was produced by Kurt Gardinier. Coming up tomorrow, for some people, the coronavirus pandemic means helping out any which way they can, from sewing masks to providing child care, to packaging and delivering meals. And we're going to hear from the helpers. That all starts tomorrow, at noon. Until then, thank you for listening. Stay safe. I'm Kojo Nnamdi.

On this last episode, we look back on 23 years of joyous, difficult and always informative conversation.

Kojo talks with author Briana Thomas about her book “Black Broadway In Washington D.C.,” and the District’s rich Black history.

Poet, essayist and editor Kevin Young is the second director of the Smithsonian's National Museum of African American History and Culture. He joins Kojo to talk about his vision for the museum and how it can help us make sense of this moment in history.

Ms. Woodruff joins us to talk about her successful career in broadcasting, how the field of journalism has changed over the decades and why she chose to make D.C. home.