Saying Goodbye To The Kojo Nnamdi Show

On this last episode, we look back on 23 years of joyous, difficult and always informative conversation.

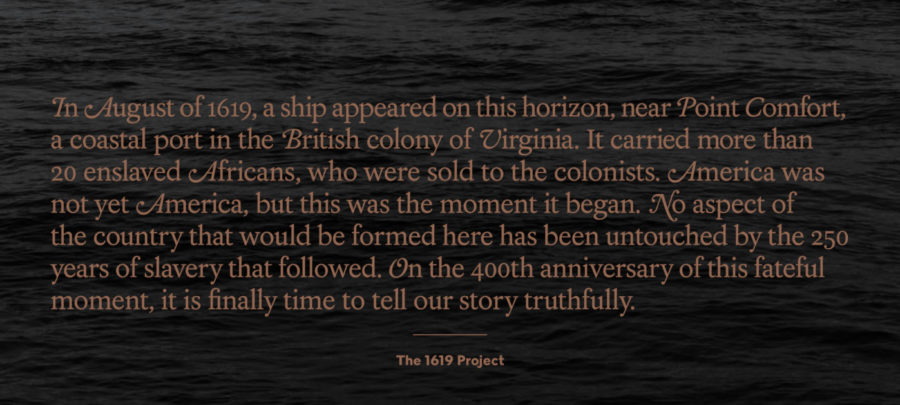

Cover of the 1619 Project.

This past August, the New York Times released the 1619 Project, a compendium of journalism and poetry examining the 400 years since enslaved Africans arrived on American soil.

The multimedia project has been widely lauded as the first mainstream journalism to “reframe American history, centering the arrival of those first few dozens of enslaved Africans.” Now, in partnership with the Pulitzer Center, the work at the core of the project is making its way into classrooms across the country — including many here in the D.C. region.

But critics argue the project is biased, incomplete, or even incorrect in its thesis. “You could say the same thing about the English common law, for example, or the use of the English language,” argued a such critic in New York Magazine. “You could say that about the Enlightenment. Or the climate. You could say that America’s unique existence as a frontier country bordered by lawlessness is felt even today in every mass shooting. You could cite the death of countless millions of Native Americans — by violence and disease — as something that defines all of us in America … but that would be to engage in a liberal inquiry into our past, teasing out the nuances.”

New York Times staff writer Nikole Hannah-Jones, who led the project, says every component was thoroughly fact-checked and verified to ensure the arguments were sound. But the core question of whether a retelling of history can ever be really complete remains — especially when studies show so few American students are taught much of anything about slavery.

We’ll learn more about the 1619 Project and curriculum from a local journalist, then hear from a high school teacher who’s used the material and a college professor who has pushed back against it.

Produced by Maura Currie

KOJO NNAMDIYou're tuned in to The Kojo Nnamdi Show on WAMU 88.5, welcome. Later in the broadcast we'll met the new Director of the Smithsonian Anacostia Community Museum. But first, this past August the New York Times released the 1619 Project, a multimedia project examining the 400 years since enslaved Africans arrived on American soil. Now the project is making its way into classrooms across the country including many here in the D.C. region, and it's reframing the way we think about slavery and race. But critics argue the project is biased, incomplete or even incorrect. And the core question of whether a retelling of history can ever be really complete is a tough one. Here to tell us more about the 1619 Project and how we teach students our difficult history is Madeline Will. Madeline Will is a Reporter with Education Week. Thank you so much for joining us.

MADELINE WILLThank you for having me.

NNAMDIMadeline, let's start with the basics. Remind us what the New York Time's 1619 Project actually is.

WILLSo it's a collection of stories, essays, photos, audio that really reframes our history from being founded in -- our country being founded in July 4th 1776 to August 20th in 1619, which is when the first enslaved Africans were brought onto U.S. soil.

NNAMDISo the Pulitzer Center is actually taking the lead in translating this work into educational material. What does that curriculum look like?

WILLYeah. So it's for teachers of all grade levels and it includes discussion questions, reading guides, lesson plans and activities. A couple of activities like they have students create a timeline of U.S. history starting in 1619 or research their own community and see how it was shaped by the legacy of slavery.

NNAMDIIs this designed to be comprehensive or is it meant to compliment what teachers are already teaching?

WILLIt's meant to compliment. It's supplementary materials. But the Southern Poverty Law Center has done a lot of research into how slavery is taught in U.S. schools and it finds that textbooks don't -- there are a lot of gaps in instruction when it comes to teaching slavery. And textbooks can be inadequate in some respects.

NNAMDIThere are widely differing perspectives on this issues. We got a note from Sabe Reid on our website. "The 1619 Project is BS. Why? Because slavery was a part of the fabric of all of Europe, South Africa as well as the USA for many years." Harry on the other hand wrote on Facebook, "Slavery is central to the foundation of the U.S. Should have been taught that in schools forever." To help make the most of the limited time we have for this segment, our producer spoke with two people with vastly different perspectives on the 1619 Project. One of them is Adrienne Glasgow, a History teacher at Dunbar High School here in Washington. Here's what she told us.

ADRIENNE GLASGOWI teach World History, U.S. History, AP U.S. History and I am an avid history lover. I actually started incorporating the 1619 Project as an enrichment activity for my lunch group just to get started. It was a part of extra credit for my U.S. History course especially the podcast, because that was discussing a lot of what we were learning in class about the Reconstruction Era. So I started off that way. And then that was able to transition into using articles pictures within the lessons that I'm doing about World War II and the black experience of soldiers in World War I. Looking at roaring 20s and those events and being able to kind of piece different articles that are in the magazine to the content.

GLASGOWAnd so that's how I've been using it now is going through for each lesson that I'm doing finding a picture or finding a poem or something in the project that connects to what I'm learning and infusing it into the classroom. It is really important to me especially to my students to find ways to engage them in the content. Especially since they look at Social Studies as something that happened a long time ago and it's completely unrelated to anything that they're experiencing. It was really important for me to use sources that our students can connect to and that they're able to see that even though this was an invent that maybe had happened a 100 years ago, 50 years ago, whether it's U.S. History or World History, the effect long term can still be seen today, and so that was what we actually use a lot of these documents for.

GLASGOWLet's read about how Nicole Hannah Jones has her article, the Idea of America and we talk about capitalism in America. When we look at our lesson the Industrial Revolution the article Capitalism in the magazine was perfect, because even though we're talking about capitalism and the effects always good to see a historical, but yet personal piece that the students can pull back to. And then always looking at, okay, in 2019 what challenges or consequences of this capitalism of bringing these slaves to America and of the year 1619 do we still see in Washington D.C. and in your current lives? A lot of my students have had the conversation of, well, why didn't I know about his before? Why aren't they teaching this to all the students in the school? Why isn't this something that everybody gets to know?

NNAMDIThat's the voice of Adrienne Glasgow, a History teacher at Dunbar High School here in D.C. Madeline, let's tease out something Adrienne eluded to in that tape. How is the 1619 Project different than how teachers usually handle slavery and race issues in the classroom?

WILLSo the 1619 Project really examines the legacy that slavery still has today. And according to the Southern Poverty Law Centers survey of teachers over half of teachers do not talk about the continued legacy of slavery in our society. So the project gives this historical voice and this historical lens to problem of racism and other social issues that we're seeing today.

NNAMDIAnd we know that there is not really any standard for what students have to learn about slavery and its effect on history, right?

WILLRight. Exactly.

NNAMDIWhy do you think teachers tend to struggle with this kind of topic?

WILLIt's a difficult topic to talk about. Teachers are worried. They don't want to terrify their black students and they don't want to make their white students feel guilty or defensive. Eighty percent of our nation's teachers are white so sometimes they feel, you know, uncomfortable talking about this.

NNAMDIThe 1619 Project has not been without criticism. Some have argued it takes a very narrow view of American history and even mischaracterizes or gets things wrong at times. The journalist, who led the project, Nicole Hannah Jones has said it was carefully fact checked. Comes down to whether you're trying to tell a story or the whole story. To hear a critique from a historian's point of view we spoke with Greg Carr. Greg is Chair of the Department of African American Studies or Afro-American Studies at Howard University.

GREG CARRIt isn't necessarily revolutionary to move from say 1776 to 1619. It still centers the kind of English presence in North America, when we know, of course, that Africans had been brought to North America as enslaved people by the Spanish over a century before. And I think that there's a bit of a sensationalist turn when you say you're rewriting the history of America when in fact you're reinscribing for me a very troubling and problematic framework. And that troubling and problematic framework really I can reduce it down to a word, citizenship. What does it mean to have a contemporary society where to be a citizen makes you more human than people who aren't? This idea, for example, that the enslaved Africans would look forward to a day when they would become citizens was really absurd if you just look at history.

CARRWhen you say, for example, that these, you know, these contemporary us, contemporary African people in this country are our ancestors wildest dreams, well, all you have to do, a quick glance through history will show that, no, their wildest dreams were to escape. More Africans fought for the British or ran away than fought for George Washington's army, for example. Their wildest dreams were to return to Africa for those first generations. Their wildest dreams were to be left alone.

CARRSo the 1619 Project is important in certainly having us have these conversations. But it is by no means at the center of or in any way really superior to the work that had been done by black and brown journalists, writers, historians. Go back and look at any ten year period in Ebony Magazine from its founding up through recently you'll see its better in some ways, more insightful and certainly differently framed curriculum work. And that's just been going on incessantly. And what I've learned in terms of curriculum over the last 25-30 years of teaching and curriculum writing is the right answers rarely exist. But the right questions can always be asked. And I don't think the 1619 Project asks right enough questions.

NNAMDIThat's Greg Carr. He is Chair of the Department of the Afro-American Studies at Howard University. Madeline, this is obviously a tough question. Do the teachers you have heard from prioritize historical completeness or just like trying to get big ideas across to students?

WILLYeah. It's tough because, you know, teachers have such a limited time to talk about this. They have a million other things that is on their plate. So I think, you know, they're trying. And I think the 1619 Project curriculum is one aspect that they can use in the classroom.

NNAMDIWhere does the 1619 Project seem to fall in the decisions that a teacher would make?

WILLWell, I think it's a lot of historical documents and historical basis that, you know, as the Southern Poverty Law Center found is lacking in schools today. So if teachers are able to use that to supplement their textbook I think that could provide a good perspective.

NNAMDIHere is Myia in Washington D.C. Myia, you are almost on the air -- Myia is not there. And Noban from Catonsville isn't there either? What's next for this project, Madeline?

WILLWell, we're seeing it go into more schools. Chicago Public Schools is actually -- gave it to every single high school Social Studies teacher to teach and more teachers are finding it as well.

NNAMDITo what extent do you find it being used in this region?

WILLI think a lot of teachers here have found it. The Pulitzer Center has it free to use to have free copies. And teachers are really hungry for this information.

NNAMDIWhat are the standards that teachers have to adhere to when teaching about slavery?

WILLWell, there's really no universal standard. It varies from place to place. And it can be -- it differs from grade level. But teachers tend to focus on more -- just kind of the basics of slavery and they don't tend to go into the varied voices and perspectives of enslaved people.

NNAMDII'll let Myia have the last word. Myia, in Washington, you're on the air. Go ahead, please.

MYIAHi, I just wanted to say that I'm very offended by the comment that I understand 80 percent of the teachers in the U.S. are white. And then the reason that we don't teach slavery at a detailed level is because the teachers don't want to offend the white students and scare the black students. And I feel that that's a cop out, because people survived slavery. So we can't even talk about it or discuss it when my ancestors and people of color's ancestors lived through it, but we can't talk about it. How do we prevent it from happening again? Slavery still exists in this world in parts of West Africa and other parts. Brown and black people around the planet continue to be exploited. And I think that the vestiges of slavery are evident in the way we dehumanize people of color. I think it's evident in the current administration, the way we're treating immigrants. It's because we don't think of people of color as humans.

NNAMDIBottom line -- we're almost out of time Myia. Bottom line is that you think the 1619 Project and others like it should be pushed in our schools.

MYIAAbsolutely. We can't --

NNAMDIOkay. You got the last word. We've got to take a short break. When we come we'll meet the new Director of the Smithsonian Anacostia Community Museum. Madeline Will, thank you so much for joining us.

WILLThank you.

NNAMDIMadeline is a Reporter with Education Week. I'm Kojo Nnamdi.

On this last episode, we look back on 23 years of joyous, difficult and always informative conversation.

Kojo talks with author Briana Thomas about her book “Black Broadway In Washington D.C.,” and the District’s rich Black history.

Poet, essayist and editor Kevin Young is the second director of the Smithsonian's National Museum of African American History and Culture. He joins Kojo to talk about his vision for the museum and how it can help us make sense of this moment in history.

Ms. Woodruff joins us to talk about her successful career in broadcasting, how the field of journalism has changed over the decades and why she chose to make D.C. home.