Saying Goodbye To The Kojo Nnamdi Show

On this last episode, we look back on 23 years of joyous, difficult and always informative conversation.

When she started reporting on domestic violence, Rachel Louise Snyder “believed all the common assumptions: that if things were bad enough, victims would just leave. That restraining orders solved the problem (and that if the victim didn’t show up to a renew a restraining order, the problem had been solved). That going to a shelter was an adequate response for victims and their children. That violence inside the home was something private, unrelated to other forms of violence.”

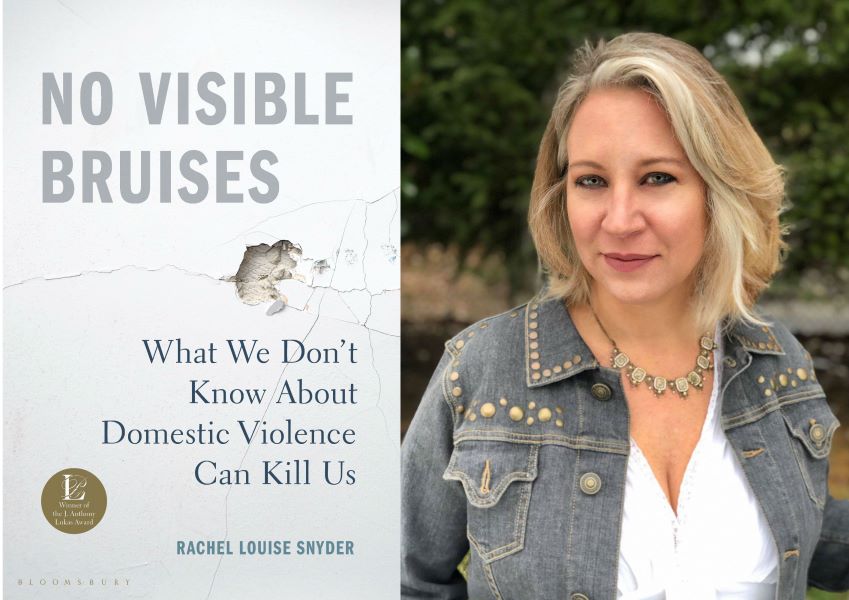

Snyder’s new book, “No Visible Bruises: What We Don’t Know About Domestic Violence Can Kill Us,” upends these assumptions through conversations with victims, abusers, advocates, police officers and others affected by domestic violence. Snyder spends time interrogating why people (often men) become violent in the first place. Even the language we use is explored: Should we say “victim” or “survivor”? “Domestic violence,” “intimate partner violence” or “intimate partner terrorism”?

We talk with Snyder about assumptions surrounding domestic violence — and solutions to curb it. And Natalie Otero, the executive director of D.C. SAFE, joins us to talk about how organizations in the region approach domestic violence.

If you’d like to learn more about resources for domestic violence victims, contact the D.C. Victim Hotline at 1-844-443-5732 or visit www.dcsafe.org.

SAFE empezó la línea de ACCIÓN. Una línea de emergencia diseñada especialmente para Latinas. La línea provee intervención de crisis y recursos inmediatos que están disponible 24 horas al día 7 días a la semana. Si usted requiere servicios en español puede llamar directamente al 1-866-962-5048. Si quiere saber más, visite esta página.

Produced by Cydney Grannan

KOJO NNAMDIWelcome back. Let's start here with a quote, "Domestic violence is like no other crime. It does not happen in a vacuum, it does not happen because someone is in the wrong place at the wrong time. It's violence from someone you know, someone who claims to love you." That quote is from Rachel Louise Snyder's new book, "No Visible Bruises: What We Don’t Know About Domestic Violence Can Kill Us." She joins us to discuss that topic. Rachel Louise Snyder is a journalist and the author of the book I just mentioned. She's also an associate professor here at American University, which carries the broadcast license for WAMU. Rachel Louise Snyder, thank you for joining us.

RACHEL LOUISE SNYDERThank you for having me.

NNAMDIAlso in studio with us is Natalia Otero. She's the cofounder and executive director of D.C. Safe, a crisis intervention agency for domestic violence in Washington. Natalia Otero, thank you for joining us.

NATALIA OTEROThank you very much, Kojo.

NNAMDIRachel, what led you to write a book about domestic violence?

SNYDERReally, you know, I had spent 20 years in various countries around the world doing stories that had humanitarian issues at their core or women's issues, social issues. And domestic violence really sat adjacent to all of those issues, whether I was interviewing women in a Kabul prison for love crimes or, you know, young brides in Niger, so much so that I didn't even really think about domestic violence. I mean, I didn't even ask about it. It's crazy now that I think about it.

SNYDERBut I moved back to the states in 2009 and the sister of a friend was working on domestic violence homicide prevention. And that just seemed like science fiction to me, like how can you prevent a homicide from happening in someone's home, you know. And so I started researching it. She gave me a bunch of different things to read. She gave me a kind of lay of the land and, you know, I was so taken with the idea that we could do something about it, it just blew my mind. It still blows my mind that we can do something.

NNAMDIYou came to understand the intricacies of what domestic violence is. What do we often get wrong when we think about domestic violence?

SNYDEROh, my, you've got six hours, right?

NNAMDISix seconds. (laugh)

SNYDERWe get everything wrong. We think that if things were bad enough victims would just leave. We think that if they don't renew restraining orders the problem is solved. We think restraining orders work. We think violent people have no desire to not be violent. We think shelters are an adequate response, lots and lots of things.

NNAMDIBefore we go any farther, I'd like to ask both of you about the language that were using here. Is domestic violence the best term to use when referring to this kind of violence? First to you.

SNYDERTo me it's an inadequate term, but we don't have an adequate replacement yet. In my book I open with a story of a woman whose husband went and got a rattle snake, poisonous rattle snake, brought it to their house--

NNAMDIWe'll talk a little bit more about that.

SNYDERYeah, and kept it in a cage and told her, you know, I'm gonna put it in bed with you or in the shower with you if you get out of line. And I don't think domestic violence can capture that sort of terror. I think terrorism gets close. I think torture gets close, but how we use the langue factors into how we understand it so it's so important.

NNAMDINatalia, what about using terms like victim or survivor?

OTEROYeah, I think that I prefer the term survivor, but I definitely think that there's a lot of conversations that we need to have as a society in these communities, because we need to flip the conversation on its side. A lot of times we focus so much on the survivor that we forget that the person in the power dynamic is the perpetrator or the batterer or -- and all of those terms are also kind of archaic. So I think we need to reevaluate for sure.

NNAMDIRachel, you debunk a lot of myths about intimate partner violence and show many of the barriers that a survivor has to overcome in order to escape an abusive relationship. In the first part of the book, you tell the story of Michelle Monson Mosure. Tell us about her life and her relationship with Rocky.

SNYDERHer story really is, in some ways, typical, very typical. She met Rocky when she was very young, 14, he was 24 so that age difference was significant. She was pregnant at 15, marry -- no, didn't marry him right away. Had a baby and then had another one, so she had two kids by the time she was 17. She still finished high school on time amazingly, but they had a very gendered relationship.

SNYDERHe believed that, you know, it was up to him to take care of bringing the money home and that she shouldn't work outside the home and that she should take care of, you know, all the kid stuff and the home life. And he really isolated her from her friends and family. He wouldn't let her have people over. He said it was a bad influence on the kids. He would say things like, I know your family doesn't like me, so I don't want to spend holidays with them. And these are the ways that he, and many abusers, manipulate their victims and slowly rest control. I mean, it's a sort of slow corrosion.

NNAMDIAnd that's the psychological abuse, but I'm thinking about what you mentioned earlier when he threatened to put a live rattle snake in her bed when she was sleeping. But that kind of psychological abuse apparently is not unique. What did you find out in terms of psychological control?

SNYDERYeah, I mean, that -- and Natalia will probably back me up here -- the victims always say that that is the worst, the emotional control, the psychological control. I mean, there was a woman that I knew in Ohio whose daughter eventually killed her abusive father. So this woman's daughter killed the father and after he died the mother had no idea how to open a bank account on her own, how to buy a car on her own. I mean, she just couldn't navigate any of those systems, she'd been so severely isolated.

SNYDERAnd, you know, in the case of Michelle Monson Mosure, she didn't have any real evidence of physical abuse. So there's so much that happens that we don't see with our naked eyes, and so we can dismiss it.

NNAMDINatalia, give us a sense of what domestic violence in this region looks like. Do the stories that Rachel recounts in "No Visible Bruises" sound familiar? Are there people suffering at the hands of someone they love, who don't realize that it rises to the level of abuse?

OTEROAbsolutely, unfortunately at D.C. Safe we see up to 8,000 survivors a year. Of those we are assessing that about 1800 survivors in the District are considered to be at high risk for re-assault or homicide. So it is a very important topic and absolutely the psychological and emotional abuse is the backbone of the power and control dynamic within the relationship. When that doesn’t work, those are the times when violence and even sexual abuse might happen, but for the most part the psychological abuse is really what is keeping victims from being able to take the steps that they need to take to consider themselves safe.

NNAMDIYou mentioned seeing 8,000 people a year at D.C. Safe, but how do we come up with numbers given that many people do not report abuse by a partner or another family member?

OTEROYeah, I mean, we try to be wherever survivors are disclosing. So we're in the emergency rooms. We have a huge array of partners so really try to be everywhere to make sure that we're accessible, but there's definitely underreporting. There are people who will go through an entire relationship and until a system actually intervenes or something happens that's fatal, nobody -- and you know what's interesting, that it isn't reported, but I think what's eerie to me is that when we have had survivors that unfortunately have been killed, when you talk to their community and you talk to their families, they all say that they were waiting, that they knew. So to some degree it's not like we don't know. It's that we don't always know how to intervene.

NNAMDIRachel, in your reporting you also find that sometimes small things can make the difference between life and death. What can go wrong when someone has reported abuse?

SNYDERWell, in the case of Michelle, I'll just go to her again, the state of Montana, it was such a high-profile case when Rocky killed her, killed their kids and then killed himself that they really all got together sort of like what Natalia's talking about. They had partners all over the state and thought, okay, what gaps can we close here. And one of the most significant things, it seems crazy, but one of the most significant things was they stopped allowing someone who's arrested for domestic violence to bail out before lunch. They can't see a judge before lunch, and it seems like it wouldn't make any kind of difference at all, but it does.

SNYDERAnd what happens is it gives the domestic violence advocates enough time to get to a victim and change locks or create a safety plan or get an abuser on GPS to put some kind of system in place to keep that victim a little bit safer. And those kinds of tiny little tweaks can really make a difference. There's like 500 of them that I mention in the book. That's probably an exaggeration actually as a journalist.

NNAMDIThere are about 500.

SNYDERYeah, but, I mean, it just is stunning to think like, oh, if we just communicate across systems, if our civil courts communicate with our criminal courts. If we can have stalking, you know, records accessible across state lines, those kinds of things will make so much difference.

NNAMDICommunication, you say, is so central to all of this. Before we go to break, Natalia, what prompted you to get into this line of work and to start D.C. Safe?

OTEROWell, actually I am a child witness. My mother was in an abusive marriage for 13 years, and so it's always been -- she fortunately was able to get out and is thriving. And so I wanted to give back, so I started vary organically, but I think, a lot like Rachel, this topic is so deep and is so entrenched in so many other things that we, as a society are suffering from that, it just started fascinating me. And it's something that I wanted to continue to do.

OTEROAnd when I moved to the District, one of the first interactions that I had with systems actors was with the Metropolitan Police Department. So I was actually training officers there for domestic violence and hearing their stories and hearing just the lack of immediate response and the lack, to some degree, of urgency just made me think, you know, this has to stop. Something has to be done about survivors not having immediate support when they need it.

NNAMDIGot to take a short break, when we come back we'll continue this conversation. If you have called, stay on the line. If you would like to the number's 800-433-8850. What myths and misconceptions do you see about domestic violence? I'm Kojo Nnamdi.

NNAMDIWelcome back. We're talking with Rachel Louise Snyder. She's a journalist and the author of "No Visible Bruises: What We Don't Know About Domestic Violence Can Kill Us." She's also an associate professor at American University. Natalia Otero is the cofounder and executive director of DC Safe, a crisis-intervention agency for domestic violence in Washington. Before I go to the phones, Natalia, what does D.C. Safe do as a crisis intervention agency? What exactly do you do to help survivors?

OTEROWell, we are the advocates that are there when survivors need us the most. We are at the D.C. Superior Courthouse helping people through this whole protection order process. We ride along with police officers. We're at the emergency room. So we're available 24 hours a day, seven days a week, 365 and are actually able to deploy advocates out into the community to meet survivors where they are.

NNAMDID.C. Safe created something called the Lethality Assessment Project in 2009. What is it?

OTEROIt is actually a multidisciplinary team of city agencies with us as the nonprofit organization that coordinates it. What it basically is is that it is an entry point for survivors, but more than anything, it allows us to actually be able to reach and screen all of our survivors for risk. So every time we meet a survivor we're asking the touch questions and figuring out, is this survivor at highest risk for homicide and re-assault.

OTEROIf they are then what we're doing is we're actually expediting and enhancing the services that we provide as a community. So it's not just safe. It's all of our partners, the courts, the police, child and family services. We are all in this together and the point is to preserve as many of the resources a survivor has and to communicate, like we were talking about earlier, and to make sure that there is a tailored intervention plan for each survivor.

NNAMDII'd like to talk to people, who are on the lines, and several have self-identified as survivors, so I will take two or three calls and then ask you to respond. Let's start with Peggy Lee in Glen Burnie. Peggy Lee, you're on the air. Go ahead, please.

PETTY LEEThank you so much. I so admire you women that are doing this for us. My abuse occurred in a military relationship with a man that was in the military. And I just want to point out that that whole atmosphere of it, if the military wanted you to have a wife we would've assigned you one. And, of course, here's this beautiful person protecting our livelihood, etcetera, etcetera and yet have the audacity to, you know, completely, you know, destroy me physically and emotionally. And of course he was very charming in person and even in the football game atmosphere it would be, oh yeah, keep her in line. Once in a while he'd slip and say something, you know, really controlling, yeah, keep her in line type of thing. So it was heavily, heavily enforced or reinforced by the military. And--

NNAMDIOkay.

LEE--I'm sure we can relate to that in this area.

NNAMDIThank you very much. I'd now like to hear from Joanna in Baltimore, Maryland. Joanna, your turn.

JOANNAHi. Thank you so much for taking my call. I’m a domestic violence survivor. I would like to tell my story but it's going to take so much time, but point here is --

NNAMDITry to be brief, please. We don't have a lot of time.

JOANNAOkay. My point here is I'm Latina and when I was living with this abuser person, I lost undocument. So my fear was, he used to tell me all the time, you're going to be deported, if you call the police. So for many years I didn't do it. I think that if many women like me who need more support from immigration, because we are so afraid. I was so afraid to lose my kids. I was so afraid to be alone, because it wasn't easy for me to find a job, because I was illegal. So I think we need more support for the system and many women are going to come out and say what they are living.

NNAMDIJoanna, thank you very much for your call. One more, Jessica in Washington, D.C., your turn.

JESSICAHi. Thank you for having my call and thank you, women, for what you're doing. I'm a survivor of domestic violence two times over and I was a child witness and survivor. My problem that I've had as a survivor, I've never received help, because I never went to the police because as a victim of domestic violence I was always told by my abuser that, you know, if I called the police no one was going to believe me. If I called the police there would be this problem or that problem or they would somehow turn it around on me. So I would get away on my own.

JESSICAA lot of programs, you know, they're not available to survivors unless you're in the hospital or unless you're involvement with the police. And that's the problem that I've ran into when wanting to find help and treatment specifically for the trauma I went through as a domestic violence survivor. And I think that if I had these programs more available to me without police involvement or knowing where to go without police involvement that maybe it could've prevented me from, you know, experiencing it the first time or the second time.

NNAMDIOkay. I'm really tight on time here, but I've got to get in quickly Robert in Herndon, Virginia. Robert, you've got 30 seconds.

ROBERTThirty seconds, thank you so much. Unfortunately I was in that situation with my mom and younger siblings and it ended up in a murder. My question to you ladies is this. With the say something, see something mentality with terrorism in the 1980s, 2000 just say no, what is the public school doing to let these kids come out and share their story to prevent these tragedies?

NNAMDIWe've heard four stories. I'll start with you Natalia. Respond at will.

OTEROYes. Well, I would like to say that I appreciate everybody who called in. I know it's not always easy to tell your story or to speak out. One thing I would say about survivors that are immigrant survivors, that I definitely see that, and I did want to share that we have a bilingual hotline for survivors, Spanish-English that I can provide, and it can perhaps be put on the website. But that's definitely something that I appreciate. And I think that everything that they said is something that we are really aware of and are trying to address. So having more entry points, making sure that survivors have the choice to involve themselves in the criminal justice system or not, depending on what their needs are. So I definitely echo what the survivors were saying.

OTEROI think in terms of what the last gentleman said, I will say that that is a gap that I think that needs to be addressed, child survivors, child witnesses. There needs to be intervention at a much earlier point in time for those children. They're falling through the cracks. It's really important that it gets addressed in a respectful and timely manner so that we're not constantly reinventing these relationships.

NNAMDIThat said, Rachel, I know you probably agree with most of what Natalia said. But, because we're running out of time, you devote the entire second part of your book to the part of domestic violence that's often not part of the discussion, the abusers, who are in many, but not all cases, men. What surprised you about the men you met?

SNYDERWell, yeah, there's so many overlaps. I mean, what surprised me the most was that they were just normal guys. They were just like my brothers, like, there was nothing identifiable about them that would suggest rageaholics. So they defied that stereotype, but the other thing that was surprising was that when they really bought into the batterers' intervention programs that they were part of, they were quite vulnerable.

SNYDERSo your first caller who talked about that military, you know, mindset, in batterers' intervention groups they call that collusion, right. Someone like, you gonna let her talk to you like that, that kind of attitude. And they really try to deconstruct that in the batterer programs. And I think, you know, your last caller with children, there are some programs out there. There's a great one called Camp Hope that's for children of survivors of domestic violence.

SNYDERBut also, more than 80 percent of the men who are incarcerated today are themselves either victims of sexual assault or the child witnesses or victims of domestic violence. So, you know, I think that our efforts going forward need to be with batterers' intervention, right, like it's new as a social science. We don't know a lot about it, and with children. To me those are the two sort of primary areas that we need to put more resources into to address exactly the kinds of things that these callers are saying.

NNAMDINatalia, are there batterer intervention programs in the Washington region?

OTERONot enough actually. And, in fact, the premier program or the one that is used the most has to be through the CSOSA, which is the equivalent of the parole board here and it has to be court appointed. So yes, I would echo that and I would actually even further say that it's also really important to have men as part of this movement. It's really important for there to be conversations about masculinity and about, you know, relationships and that's the other side of the coin. I think definitely there needs to be interventions and support and help for batterers also, very bad term, but like who want to seek assistance.

NNAMDIJust briefly, what resources would you point people to if they're experiencing or know someone who's experiencing domestic violence in this region?

OTEROYeah, well, there is the D.C. victims' hotline that actually is for all victims of crime. So that encompasses also sexual assault. But I think that's the starting point for the District. If you need assistance, they're able to actually put you in contact with agencies. We are available as well.

NNAMDIAnd you can find a link to D.C. Safe on our website kojoshow.org. And I'm afraid that's about all the time we have. Natalia Otero is the cofounder and executive director of D.C. Safe. Thank you so much for joining us.

OTEROThank you.

NNAMDIRachel Louise Snyder is a journalist. She is author of the book "No Visible Bruises: What We Don't Know About Domestic Violence Can Kill Us." Thank you so much for joining us.

SNYDERThank you, Kojo.

NNAMDIThis conversation about domestic violence was produced by Cydney Grannan and our check in with D.C.'s director of Nightlife and Culture was produced by Monna Kashfi. Coming up tomorrow on the Politics Hour we'll check in with Montgomery County Councilmember Will Jawando about the county's new budget and we'll meet Andres Jimenez. He's an environmentalist and Democrat trying to represent Fairfax County in the Virginia House of Delegates. That all starts tomorrow at noon, until then, thank you for listening. I'm Kojo Nnamdi.

On this last episode, we look back on 23 years of joyous, difficult and always informative conversation.

Kojo talks with author Briana Thomas about her book “Black Broadway In Washington D.C.,” and the District’s rich Black history.

Poet, essayist and editor Kevin Young is the second director of the Smithsonian's National Museum of African American History and Culture. He joins Kojo to talk about his vision for the museum and how it can help us make sense of this moment in history.

Ms. Woodruff joins us to talk about her successful career in broadcasting, how the field of journalism has changed over the decades and why she chose to make D.C. home.