Saying Goodbye To The Kojo Nnamdi Show

On this last episode, we look back on 23 years of joyous, difficult and always informative conversation.

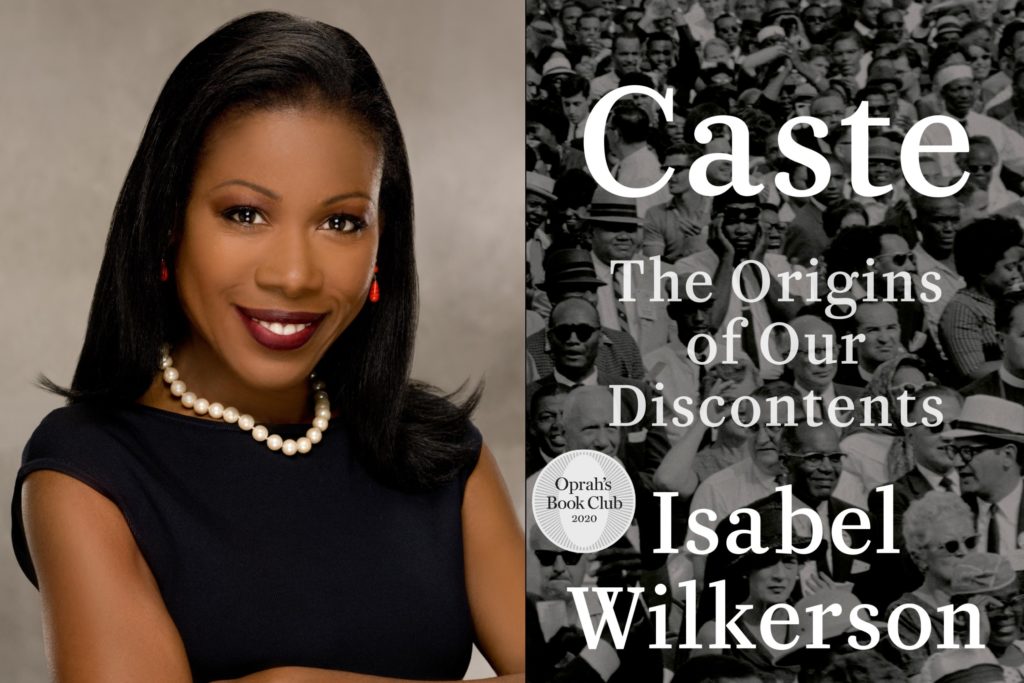

Isabel Wilkerson is the author of the New York Times Bestseller "The Warmth of Other Suns." Her most recent work is called "Caste."

I embarked upon this book with a similar desire to reach out across the oceans to better understand how all of this began in the United States: the assigning of meaning to unchangeable physical characteristics, the pyramid passed down through the centuries that defines and directs politics and policies and personal interactions. What are the origins and workings of the hierarchy that intrudes upon the daily life and life chances of every American? That had intruded upon my own life with disturbing regularity and consequences?

In her book “Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents,” author Isabel Wilkerson — the Pulitzer Prize-winning writer behind “The Warmth of Other Suns” — analyzes the unspoken caste system that has shaped America. Even more than race or class, Wilkerson writes, a caste system influences our lives, behavior and destinies. Connecting the caste systems of Nazi Germany, India and America, Wilkerson explores the pillars that uphold caste across civilizations. She shows how caste is experienced in the daily lives of individuals throughout history and today, and expresses the hope of progress in the recognition of our common humanity.

Produced by Julie Depenbrock

A caste system is an artificial construction, a fixed and embedded ranking of human value that sets the presumed supremacy of one group against the presumed inferiority of other groups on the basis of ancestry and often immutable traits, traits that would be neutral in the abstract but are ascribed life-and-death meaning in a hierarchy favoring the dominant caste whose forebears designed it. A caste system uses rigid, often arbitrary boundaries to keep the ranked groupings apart, distinct from one another and in their assigned places.

Throughout human history, three caste systems have stood out. The tragically accelerated, chilling, and officially vanquished caste system of Nazi Germany. The lingering, millennia-long caste system of India. And the shape-shifting, unspoken, race-based caste pyramid in the United States. Each version relied on stigmatizing those deemed inferior to justify the dehumanization necessary to keep the lowest-ranked people at the bottom and to rationalize the protocols of enforcement. A caste system endures because it is often justified as divine will, originating from sacred text or the presumed laws of nature, reinforced throughout the culture and passed down through the generations.

KOJO NNAMDIWelcome back. In her new book "Caste," award-winning author and D.C. native Isabel Wilkerson analyzes the origins of the unspoken caste system she says is built into the fabric of America. Connecting the systems of Nazi Germany, India and the United States, Wilkerson explores the pillars that have upheld this artificial hierarchy and focuses in on how individuals experience it in their daily lives.

KOJO NNAMDIJoining us to discuss it is Isabel Wilkerson herself, winner of the Pulitzer Price and the National Humanities Medal. She's the author of "The Warmth of Other Suns: The Epic Story of America's Great Migration." Her new book is called "Caste: The Origins of our Discontents." Isabel Wilkerson, thank you for joining us.

ISABEL WILKERSONWell, thanks for having me.

NNAMDII thought we'd start off with a very basic question. What is caste, and how does it operate as a system?

WILKERSONWell, caste is essentially an artificial, arbitrary, graded ranking of human value on a society. And it's that hierarchy that's embedded that we cannot necessarily see, but that in the same way that the houses that we live in have pillars and joists and beams that hold up the structure of one's house, that there's a structure, an infrastructure to a society that determines one's standing and respect and benefit of the doubt accorded them, access to resources or lack thereof, assumptions of competence and intelligence and even beauty.

WILKERSONAnd these are accorded to an individual based upon the group into which they're born, how that group is seen, where that group is positioned in the hierarchy in terms of power and access. Through no fault or action on one's own, you're born into an infrastructure. And the infrastructure dates back to basically before there was a United States, back to the time of enslavement in which the colonists positioned themselves, which would not be surprising, at the very top of the hierarchy that they were creating. And then they brought in Africans to be enslaved. And those enslaved people were then positioned, by definition, at the bottom of that hierarchy.

WILKERSONAnd so we still live with the aftereffects, the shadow of the originating bipolar structure, hierarchy that was created at that time built up over the laws and customs that were created to keep Africans in particular in a fixed place, and that we live with, to this day, in many of the things that we might see even in our current era.

NNAMDIWhen most people hear caste system, I think they probably tend to think of India where there continues to be a fairly rigid hierarchy. They don't necessary think of the U.S. But what you just described is very much an American phenomenon, isn't it?

WILKERSONWell, the idea of people, the human impulse to stratify is deeply human and widespread, which is one of the reasons I chose to look at what's happened in other societies in order to better understand our own. But you're absolutely correct that, you know, the most recognizable caste system would be the one of India, which is ancient, thousands of years old, I should say has been outlawed in the 1950s.

WILKERSONSo, in the same way that the United States had civil rights legislation in the 1960s that outlawed discrimination against African Americans and other groups based upon race, religion, national origin, gender and those kinds of things, that the laws are there, but that sometimes these things can still persist, because they go deeper than just the laws. They are part of the customs and the ways of thinking, the assumptions and the stereotypes that were undergirding the original hierarchy to begin with.

NNAMDIIsabel Wilkerson, "The Warmth of Other Suns," which was published in 2010, focuses on the great migration of African Americans from the South to the north during the 20th century. What led you to "Caste?" Why did you choose to research and write about caste for your second book?

WILKERSONThank you for asking. In fact, "The Warmth of Other Suns" had its 10th anniversary yesterday. And surprisingly, you know, and gratefully, it has been such a beloved book, that it's actually on the New York Times Bestseller list again after all this time. But it was through "The Warmth of Other Suns" that I came to use the term caste. And that was because I was writing about the outpouring of six million African Americans from the Jim Crow south seeking freedom, seeking liberty, seeking refuge really in the rest of the country.

WILKERSONAnd in describing what they were leaving and what they had been born into in the Jim Crow South, I came to recognize that the word racism was not sufficient. It's obviously an important part of our understanding of human relations and in our country, but that that word alone did not capture the nature and extent of the restrictions on them. Because this was a world in which into the 1970s it was -- into the 1960s and '70s, it was actually against the law for a black person and a white person to merely play checkers together in Birmingham.

WILKERSONThis was a world in which, into the 1960s and '70s, there were separate Bibles. There was a black Bible and altogether separate white Bible to swear to tell the truth on in court in southern courtrooms. So, this was a very rigid system that was built upon an infrastructure of controlling the actions and creating boundaries and policing of boundaries to keep people in their place to uphold this hierarchy. And so that's how I came to use the word caste originally in my own work. And then I decided, with this book, to explore that idea even further.

NNAMDII'm wondering if you wouldn't mind reading a passage from the new book "Caste," starting at page 11.

WILKERSONLet me get that. Let me read from that.

NNAMDIThank you.

WILKERSONThank you for asking. "We have long defined earthquakes as a rising from the collision of tectonic plates that force one wedge of earth beneath the other, believe that the internal shoving match under the surface is all too easily recognizable. In classic earthquakes, we can feel the ground shutter and crack beneath us. We can now see the devastation of the landscape or the tsunamis that follow."

WILKERSON"What scientists have only recently discovered is that the more earthquakes, those that are easily measured while in progress and instantaneous in their destruction, are often preceded by longer, slow-moving catastrophic disruptions rumbling 20 miles or more beneath us. Too deep to be felt and too quiet to be measured for most of human history. They are as potent as those we can see and feel but they have long gone undetected because they work in silence, unrecognized until a major quake announces itself on the surface."

WILKERSON"Only recently have geophysicists had technology sensitive enough to detect the unseen stirring deeper in the Earth's core. They are called silent earthquakes and only recently have circumstances forced us, in this current era of human rupture, to search for the unseen stirrings of the human heart to discover the origins of our discontents."

NNAMDIThat's Pulitzer Prize-winning author Isabel Wilkerson reading from her newest book, "Caste." You're not just speaking geologically, here, Isabel. What do these silent earthquakes represent?

WILKERSONThey represent the rise of the divisions and the ruptures that have been present off and on throughout our history. We live in continuum in which there's progress that's made. And then there's this backlash and a receding from that progress. And then there's a plateau, and then there's -- yet, again, the cycle begins. And so, we are in the midst of a continuum in which there have been progress made in terms of equality and inclusion of people of all backgrounds.

WILKERSONAnd then we seem now to be in a moment of great upheaval, as people attempt to respond to what people might feel are changes that they're not accustomed to, changes that they do not feel adjusted to, threatened by the changes and growth. You know, it's said that in 2042, the country will no longer look as it has looked for, you know, the majority of its history. Meaning that the majority of our country, historically -- which have been people who are identified as white -- would no longer be in the majority.

WILKERSONAnd that means that that would be a new way of looking at ourselves if these projections hold. And it means that for everyone in the country, there would have to be a new way of looking at ourselves, a new way of even defining who is American, who are we as a country, what do we want to be, who do we want to include. These are some of the existential questions that I think we, as a country, are facing. And it calls upon everyone to kind of reexamine and inspect and reflect. And for some people it can feel very threatening and uncertain, a time of uncertainty.

NNAMDIWe're talking with Isabel Wilkerson. Her new book is called "Caste: The Origins of our Discontents." You draw comparisons between the plight of black people in America and that of the untouchables, the lowest caste in India, using, in part, the experience that Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. had when he went to India. Could you tell us a little bit about that and about what similarities did you take note of in your research?

WILKERSONYes, absolutely. In fact, it was in 1959 that Dr. Martin Luther King made his first trip to India. You know, he was very inspired -- for the civil rights movement that he led, he was inspired by the nonviolent approach that had been taken by Mohandas K. Gandhi. And so, he was anxious to be able to go and see India for himself.

WILKERSONAnd upon arrival he was met as a visiting dignitary in most places that he went. And then he made a visit to a school where Dalit children -- who were formerly known as untouchables, now known as Dalit -- were attending this school. And so, upon arrival at the school, the principal introduced Dr. King to the students and said, young people, I'm happy to introduce you to a fellow untouchable from America.

WILKERSONAnd when the principal said that, Dr. King heard those words, and they landed a little uneasily to his ear. He was a little bit peeved, actually, to have been described by Indians there as an untouchable. He did not see himself in that way. He had, in fact, been treated as a visiting dignitary. He had had dinner with the prime minister, so he did not see himself that way.

WILKERSONBut then he thought about it, and he thought about the then-20 million African Americans who he was advocating for. He thought about how, at that very moment in 1959, the majority of African Americans, the majority of black people were not able to vote, not really. They were not able to go and use public facilities. So, there were tremendous restrictions. And, of course, their effort to realize acceptance as full citizens were being met with violence.

WILKERSONAnd so, he thought about it and he said, I am an untouchable. And every black person in America is an untouchable. So, he made this recognition, Dr. Martin Luther King made this recognition that he and black people in the United States were assigned to the lowest caste, that they were American untouchables. And, interestingly enough, Indians themselves, the Dalits there recognized it, as well. The untouchables recognized a connection, and so did Dr. Martin Luther King.

NNAMDIHere now is Jim in Rockville, Maryland. Jim, you're on the air. Go ahead, please.

JIMThanks very much, Kojo. I love your show. I listen as often as I can.

NNAMDIThank you.

JIMQuestion for the author. I must say, I have not read your book. In this country, it is possible to be educated out of the status in which one was born. And whereas, in India, it's my understanding that education or opportunity really did not matter. A person who was born into a caste stayed there. What do we do -- how does your theory adjust to the fact that one can move out of the economic situation or class situation in which they were born?

NNAMDIIsabel Wilkerson?

WILKERSONThat's an excellent question. Interestingly enough, as I indicated, India outlawed untouchability in the 1950s. And, in the time since then, as here in the United States, there have been untouchables who've been able to get an education, to be able to rise to some positions. There are lawyers and physicians, people who were able to make it through, with great difficulty and hard work they are able to do that.

WILKERSONThere even was a president who was from the untouchable -- formerly untouchable Dalit caste. So, there have been progress that's been made. Even in the strictest and oldest caste system in the world, there have been achievements that they have been able to make. As for in our country, one way to look at caste is to think of caste as the bones, race as the skin and class as the clothes, the diction, the accents, the education that a person can acquire in order to try to make the most of their innate talents.

WILKERSONAnd yet, there are many cases in which class does not protect someone from what was the underlying issues of caste. Because race is the social signifier of where your -- you know, what you look like as a signifier, the tool that indicates presumably where you fit on the hierarchy. And so if you think about it -- well, there's one example I could give, which is of the editor of British Vogue, or example. This could be the United States or here.

WILKERSONThe editor of British Vogue, who would have been one of the most best-dressed, sophisticated people on the planet, was walking into his own building and was told by the security guard that he would have to use the freight elevator of his own building. There have been so many cases that we've seen in this country of African Americans or black people just trying to get into...

WILKERSONThere's a case in St. Louis where a marketing executive was walking into -- trying to get into his own condo building in St. Louis, for example. And there was a woman, from what I would consider -- I would call the dominant caste, who blocked him as he tried to get into his own building. And it was not fear that was active with her.

WILKERSONShe actually followed him all the way to the elevator, went up in the elevator with him to assure herself that he actually belonged, because caste has a lot to do with the policing of boundaries, surveilling of boundaries, and followed him all the way to his apartment, where he then opened the door and then closed the door. But this is actually a video that anyone can see. It was viral for a time. And so, what this is saying is that if you can act your way out of it, it's class. If you cannot act your way out of it, it's caste.

NNAMDIAnd we all remember that Oprah Winfrey was stopped in Paris going into a high-end store. You could hardly have known, Isabel Wilkerson, that we'd be in the midst of a racial reckoning as you worked on this book. I can't help but think about how what you write resonates at this moment. What do you make of what's happening in the country right now?

WILKERSONWell, I think that this is a reckoning. And I think that this is a growing awareness. I hope that we're on the cusp of an awakening as people who have not had to deal with the day-to-day consequences of caste come to realize what their fellow citizens have actually been having to endure. You know, the kinds of things that have been occurring. We have viral videos that show up, you know, almost on a weekly or daily basis, of everyday intrusions of caste, where someone is just at a Starbucks waiting for a friend and the police are called on them. Someone calls the police on them and they're arrested, to the more extreme examples that we have seen all too often, Rochester, Kenosha, Minneapolis, where people lose their lives.

WILKERSONYou know, unarmed people are losing their lives at the hands of the state. And these are people who are from what would be considered, historically, the subordinated caste in our country. So, we are seeing this with our very eyes. We have seen that people are, I think, wanting to know the true history, the full comprehensive history of our country. One of the things that we need to do as a country is to get on the same page about what has gotten us to this point. And that means really truly confronting and reckoning with our history.

NNAMDIHere now is Craig in Annapolis, Maryland. Craig, you are on the air. Craig, go ahead, please.

CRAIGSure. Thank you. I love your show, and I absolutely can't wait to read the book, Isabel. It sounds absolutely amazing. And I believe this process, I do believe your theory. I wanted to know, in America, do you believe that this caste system also places people -- Hispanic people on this ladder, or on this bottom, with African Americans?

CRAIGBecause I know a lot of the research I do about disparities, we talk about the difference between African Americans and access to resource, etcetera. But also, we had to include Latinos, as well. But I'm starting to see where Latinos tend to be stepping up a ladder, per se. So, do you believe this caste system classifies them, as well?

WILKERSONAbsolutely. The originating caste system was a bipolar one that had people who were closest to the colonists, the closest that you could be to being British. And often, gender is part of this, as well, then the more likely, you would be in that dominant caste. Then there was the bottom caste which would've been enslaved people. There were the outcasts which would've been people who were indigenous and who were -- the decimation of their numbers and then the exiling, you know, out to the west. So, that was the essential caste system structure, as we have inherited it.

WILKERSONAnd then what has happened is that, over time, as people come from outside of any of those poles, they have to find a way to navigate a preexisting order. And that meant that many people who came from, say, Western and -- from Eastern and Southern Europe arriving to this country were then assigned to a category of white. They would never have been identifying themselves as white before. They would have been Hungarian or Polish or Irish, but they would not have been considered white until they get to the United States, because that's a political category that was created when this -- you know, as a way of delineating who was what in this country.

WILKERSONAnd then as people have come from other parts of the world, from Asia, from parts of Latin America, then they have to also navigate away. And so, I describe them as middle castes. These are people who are not at either pole, but they have to find a way to navigate in this structure. And what human beings often do is that in order to survive, they may more likely try to -- feel forced to exceed to the expectations of the dominant group in order to survive.

WILKERSONAnd so that means that people who are of Latino or Asian descent, they're in the middle. and they can move between these poles. But very few people would choose to be identified with the subordinated lowest caste if they had a way to not do that. And that puts pressure on everyone. Even people who are coming from other parts of the African Diaspora also are forced into figuring out a way to navigate what is ultimately an artificial, arbitrary graded ranking of human value in a society.

NNAMDIThank you very much for your call, Craig. We only have about a minute left, Isabel, but you write that the Nazis were, in fact, studying Jim Crow laws for their own edification. In what ways did the treatment of Jewish people in Germany align with the treatment of black people in America?

WILKERSONYes. Well, I must say that I came to the idea of bringing Germany into this because of Charlottesville, where the protestors pulled together the symbolism of Nazi Germany and of the Confederacy into one. And that's what pulled me into even looking at Germany in the first place.

WILKERSONAnd then in looking at it, I was stunned to discover that German eugenicists were actually turning to and consulting with American eugenicists in the years leading up to the Third Reich. That American eugenicists had books that they were writing that were big, big sellers in Germany in the years leading up to the Third Reich. Now, it's important to note that the Nazis needed no one to teach them how to hate.

WILKERSONBut what they did was they actually sent researchers to study America, to study the American laws, to study how America and particularly the Jim Crow south, had found a way legally, in their view, to subordinate and subjugate African Americans. They studied the Jim Crow laws. They studied the anti-miscegenation laws. All of these things they studied, and also the definition of black...

NNAMDIJust about out of time.

WILKERSON...as they were leading up to their own laws.

NNAMDIIsabel Wilkerson is the winner of the Pulitzer Prize and the National Humanities Medal. She's the author of "The Warmth of Other Suns: The Epic Story of America's Great Migration." Her new book is called "Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents." Isabel, thank you so much for joining us.

WILKERSONThank you so much for having me.

NNAMDIThis segment with Isabel Wilkerson about her new book "Caste" was produced by Julie Depenbrock. And our conversation about local voting in the upcoming elections was produced by Kurt Gardinier. Coming up tomorrow, many star athletes are voicing support for the Black Lives Matter movement. What happens when sports and activism intersect?

NNAMDIPlus, you may have caught a 13-year-old boy who stutters deliver an inspiring speech at the Democratic National Convention. Well, millions of people stutter. How should we understand stuttering, both as speakers and as listeners? It all starts tomorrow, at noon. Until then, thank you for listening and stay safe. I'm Kojo Nnamdi.

On this last episode, we look back on 23 years of joyous, difficult and always informative conversation.

Kojo talks with author Briana Thomas about her book “Black Broadway In Washington D.C.,” and the District’s rich Black history.

Poet, essayist and editor Kevin Young is the second director of the Smithsonian's National Museum of African American History and Culture. He joins Kojo to talk about his vision for the museum and how it can help us make sense of this moment in history.

Ms. Woodruff joins us to talk about her successful career in broadcasting, how the field of journalism has changed over the decades and why she chose to make D.C. home.