Saying Goodbye To The Kojo Nnamdi Show

On this last episode, we look back on 23 years of joyous, difficult and always informative conversation.

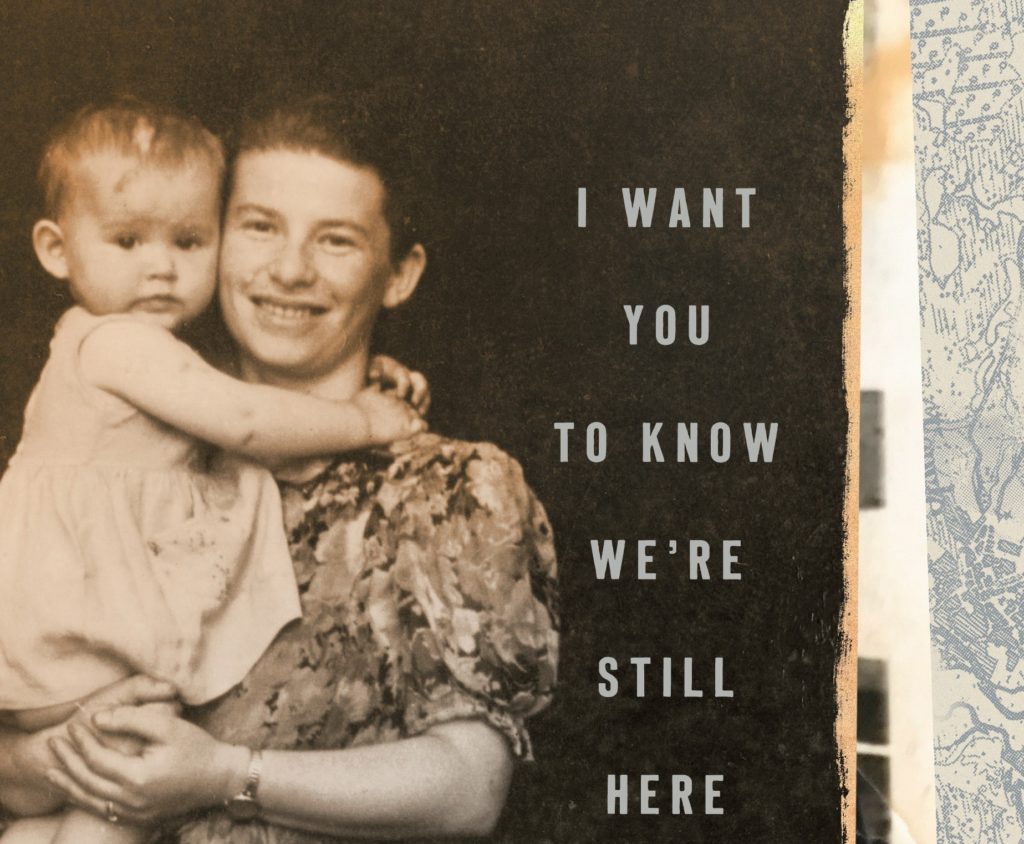

Esther Safran Foer held by her mother, Ethel Safran, in a displaced person camp in Germany after World War II.

The founding CEO of one of the region’s most vibrant religious and cultural institutions, Sixth & I, has helped many people share their stories. Now she shares her own.

Esther Safran Foer asks a jarring question in the introduction to her new memoir, “I Want You To Know We’re Still Here.”

“How do you remember someone who has left no trace?”

Safran Foer knew from an early age that her parents were the only members of their families who survived the Holocaust. But it wasn’t until she was in her early forties that her mother revealed that her father had been married before and had a little girl.

Safran Foer’s memoir is the story of her journey to discover all that could be known this half-sister and the many other leaves on her family tree’s branches buried in the Holocaust. It’s an immigrant’s story of horror, but also of hope — hope that found a home in Washington, D.C.

Produced by Lauren Markoe

KOJO NNAMDIYou may recognize the name Esther Safran Foer. Maybe you know that she was the founding executive director of Sixth & I, a vibrant cultural and entertainment center in the District that is also a synagogue. You may also know her as the mother of three rather famous literary sons, Frank, Joshua and Jonathan Safran Foer. But you may not know the story of her family in the old country, and that's because until not so long ago, she didn't know it, either.

KOJO NNAMDIIt's the story of how her parents survived the Holocaust, of her father's death and what lived on after the destruction of Jewish life in Europe, and it's all chronicled in her new memoir called "I Want You To Know We're Still Here." Esther Safran Foer, welcome to the broadcast. Thank you so much for joining us.

ESTHER SAFRAN FOEROh, thank you for having me. I'm delighted.

NNAMDICan you give our listeners an idea of what your memoir is about? Would you read the first few paragraphs for us?

FOERSure, I'd be delighted. My birth certificate says that I was born on September 8th, 1946 in Ziegenhain, Germany. It's the wrong date, the wrong city, the wrong country. It would take me years to understand why my father created this fabrication, and why, each year, my mother tiptoed into my room on March 17th and gave me a kiss and whispered, “Happy birthday.”

FOERPiercing together the fragments of my family story has been a lifelong pursuit. I'm the offspring of Holocaust survivors, which, by definition, means there is a tragic and complicated history. My childhood was filled with silences that were punctuated by occasional shocking disclosures. I understood there was a lot that I didn't know besides the secret of my invented birthday.

FOERMy parents were reluctant to speak of the past, and I learned to maneuver around difficult subjects. When I was in my early 40s, preparing to give a talk at a local synagogue, I decided this might be a good opportunity to fill in a few of the gaps of our family's story. I sat down with my mother in the pink kitchen of her 1950s suburban tract house, on a street where most of the other houses were occupied by families of Holocaust survivors.

FOERSitting at her faux-marble laminate kitchen table, I started with a few questions about my father and his experience during the war. He had been an enigma, a mercurial figure that all conversation danced around, even in my own head. My mother took a sip of the instant coffee that she loved, and casually mentioned my father had been in a ghetto with his wife and daughter. He'd been on a work detail when they were both murdered by the Nazis.

FOERAbsolutely stunned, I blurted out, he had a wife and daughter? Why haven't you told me this before? How can you be telling me this now, for the first time? I'd grown up surrounded by ghosts, haunted by relatives who were rarely talked about, and by stories that no one would share.

NNAMDIEsther Safran Foer, reading from her new book, called, "I Want Them to Know We're Still Here." It is her personal search into her family history. Well, your birth certificate had the wrong date, wrong time, wrong country. What are the actual circumstances of your birth? When and where, and to whom were you born?

FOERSo, that's really interesting. Well, my parents, the name of my parents was right. I was born in Lodz, Poland a few months earlier, March 17th. And why would this be created? It's kind of interesting to talk about this right now, in this time. We came to the United States -- well, let me start with -- there were 6 million or more Jews murdered in the Holocaust. And there were somewhere between 250,000 and 300,000 Jewish refugees, refugees who had nowhere to go. Nowhere to get out of the graveyard of Europe.

FOERAnd we were in Poland. My parents were making their way west. They had been in eastern Poland and my mother in Russia and even in Asia, escaping from the Nazis. Like these other refugees, they were making their way west, trying to figure out what to do with the rest of their lives. Lodz became a natural gathering place, because Warsaw, the capital, had been totally leveled. So, suddenly, there were -- Lodz had had a big ghetto. It was wiped out, but suddenly there were over 50,000 Jews who were making their way west in Lodz, like our family.

FOERBut it became increasingly clear that there were pogroms continuing, that the people who lived in these homes and cities didn't expect Jews to come back. And we were visited -- my father had opened a business with some partners, and we were visited by someone, I think, from an Israeli organization or a Jewish organization -- this was shortly after I was born -- who said, it's time to get out. You've got to get out of Poland. Not only were there pogroms, but the Iron Curtain was coming down.

FOERAnd so, sometime when I was a few months old my family snuck across the border, actually, in a false-bottom truck where my mother had to gag me for part of the trip, so that I wouldn't give away our location. And we made it into Germany where Jewish refugees and other refugees were gathering. Germany was going to be the stopping off point to try to go somewhere west, but nobody wanted these Jewish refugees.

NNAMDISo, you spent your toddler years in a DP camp. What is that and how...

FOERIn a DP camp, a displaced person's camp. And, you know, for me, I have so many pictures of my life during that time. Pictures in this white, furry rabbit coat, pictures on a tricycle. The DP camps had the largest birth rate of anyplace in the world. These were people trying desperately to rebuild their lives and to create new life. And, in my mind, these were happy times, because this is all I knew.

FOERBut, in retrospect, looking at pictures, reading about this period, we lived in an army barracks -- in our case, one that had just been converted from a prisoner of war camp. It was dirty. There weren't any facilities. There was no place to cook. They weren't heated. And we had no place to go. The refugees cleaned up these camps and were waiting, were waiting for a way out of Europe.

NNAMDIBut you had parents with you who loved you, and maybe that's why you remember it in a more pleasant manner. So, how and when did you wind up in Washington, D.C.?

FOERWell, we wanted out. My mother kept placing ads, and I guess my father did, too, looking for relatives who could sponsor us. You couldn't just -- nobody in the world wanted us. And you couldn't just come to America. You had to have somebody sponsor you, guarantee that you wouldn't be a burden to the system, that you had a job and a place to live and weren't displacing somebody else. This may all sound kind of familiar right now, in this time of refugees. And I have to say I so identify with these people.

FOERFinally, the 1948 DP Immigration Act was going to be our ticket out of Europe. The U.S. Congress passed an immigration act that was going to allow 200,000 displaced persons into the United States. But it was blatantly anti-Semitic. It was so anti-Semitic, Truman didn't even want to sign it. It specified that, in order to come to the United States, you had to have been in a DP camp in Germany, or you had to have been in Germany by December of 1945. Well, I was born March of '46. If my parents had admitted that, it would've been clear that they weren't in Germany, and that we wouldn't have qualified.

FOERSo, with a lot of falsification of documents, including my birth certificate, we snuck into the U.S. under the 1948 DP Immigration Act, an act that admitted about 80,000 Jews. And I have since learned that there were about 10,000 Nazis that were able to get into the U.S. under that act. That was later changed by Congress in the '50s, but in '48, it was blatantly anti-Semitic. It worked against the Jewish refugees. We got to Washington, because we had family here.

NNAMDIRight, had an uncle here who had a house, I think, on 3rd Street Northwest. What did your parents...

FOERExactly, you read the book. Yes.

NNAMDIYes. What did your parents do after they settled here?

FOERWell, we stayed with my aunt and uncle for a very short time. My mother remembers the first meal was a tuna fish sandwich. And she had no idea what tuna fish meant. They weren't serving tuna fish in eastern Europe. We lived with them for a couple of weeks. We got our own apartment. My father got a job, and our family thrived here. It took years. There were additional tragedies, but we found hope in Washington, and we're still here.

NNAMDIWell, you mentioned additional tragedies. Your memoir is, in large part, the story of your journey to demystify your father's death. When and how did he die?

FOERSo, my father died in 1954, which was just a few years after we came to the United States. And he committed suicide, something that we never talked about, never. I mean, I was eight years old. In addition to all the tragedies of the Holocaust, we couldn't talk about this new tragedy in our lives. I will probably never really understand why he did that, but, at least in my mind, having survived the Holocaust, having lived in a ghetto, having had all of his family killed, including his wife and a young daughter, I've got to believe contributed to how difficult it was to continue to live.

NNAMDIBy the way, how did your mother survive the war?

FOERSo, my mother's the ultimate survivor. And even in this time of this pandemic, I'm taking lessons from her. She was always prepared for everything. Even in the United States there was always a pantry filled with anything you would need to survive for several months. She was always somebody -- she survived by going east. As the Nazis were approaching her village, she and several of her friends instinctively just picked up and ran, and followed the retreating Russians.

FOERAnd, in her case, what's really interesting, and is indicative of the kind of person she was, it was in June. She went back to her house, she got her winter coat. You know, and this is a beautiful day in June. And she took a pair of scissors and a change of clothes. And, ultimately, that winter coat saved her during the years that she was in Russia, deep into Asia, escaping the Nazis. And the scissors enabled her to cut up the coat and to patch it up.

FOERShe was, in so many way, the ultimate survivor, and I think that's what she taught me, and I hope it's what she's taught my children and our grandchildren, that you can go on. That you have to believe in the future and have hope and find the resilience. And it's certainly a message for our time, isn't it?

NNAMDIIt certainly is. You have a photograph of your father with three other people, people you understood to have hidden him for part of the war. You were curious about your father, his family and the people in the photo. But it was your son, Jonathan, who was the first to try to figure out who had posed for that photo. What did he discover?

FOERExactly. One of my sons likes to say that I used child labor, that before I was ready to ask the difficult questions and do this search myself, I found ways for them to do the work for me. Our oldest son, Frank, who lives in Washington, I encouraged him, for his high school senior project, to interview my mother. And, hence, we have hours and hours of taped interviews. He would take her shopping to all the stores where she was going to find bargains and sit with a tape recorder between the two of them.

FOERAnd then, when Jonathan was in college, I think his majors were philosophy and creative writing, and he had to do a senior project, but wanted to spend the summer in Europe. And I suggested that what he might do is go into Ukraine, once he was already in Prague, and try to find these people. And, of course, he didn't find them. He didn't find anything. (laugh)

NNAMDIBut his search ended up in a burst of creativity. What did he do after that trip?

FOERWell, it was a tremendous burst of creativity, and we were so lucky. It turned into an international bestseller and a movie. And, as a result of that, people started to come to me and they said, oh, my God, he got it all wrong. This wasn't the place and these weren't the people. And, let me tell you, I know the real story.

FOERAnd I ended up talking to people, literally, in different parts of the world, in Brazil and in Israel. People would find me, or I would find them, and they would each give me a little bit of the truth. And that's what I was able to piece together, when I was able to go back about 11 years after Jonathan did, and find the descendents of this wonderful family that hid my father.

NNAMDIWithout giving away the answer to one of your family's most shrouded mysteries, how were you able to find the answers to questions about your half-sister and your father's family that had eluded your son?

FOERI'm sorry, what was the last thing you said?

NNAMDIHow were you able to find out the answers to the questions about your half-sister and your father's family, the questions that had eluded Jonathan? Are those conversations you referred to that you had with people afterwards, who said, I know the story?

FOERWell, a couple of things. First of all, he didn't actually go to the right place. I didn't have all the information. And based on what I had learned after his trip, I started working databases. I hired somebody in Ukraine who could do advanced work. I even hired an FBI forensics photographic expert -- yeah, that was really one of the most fun parts of the journey -- who could analyze the photograph that I had and compare it to photographs that were being sent to me by this researcher in Ukraine.

FOERAnd, ultimately, without giving it all away, he looked at them. We studied them for an hour -- a very expensive hour, by the way -- and he said, “I can't tell you it's them.” And then he looked at me and said, “But I can't tell you it's not them.” And he started to give me clues, for when I went to Ukraine, what I should be looking for, how I should be measuring the distance of features between ears and earlobes and nose, and also to look at the clothes people wear. These were not people with large wardrobes.

NNAMDIWow. Well, I'm afraid we're just about out of time. This was your first book. Do you have another one in you?

FOER(laugh) Oh, I would love to, but for right now, I hope everybody will enjoy this one.

NNAMDIEsther Safran Foer is the former executive director of Sixth & I Cultural Center and Synagogue, and the author of "I Want Them to Know We're Still Here." Esther Safran Foer, thank you so much for joining us. Good luck to you.

FOERThank you so much. Have a good day.

NNAMDIYou, too.

On this last episode, we look back on 23 years of joyous, difficult and always informative conversation.

Kojo talks with author Briana Thomas about her book “Black Broadway In Washington D.C.,” and the District’s rich Black history.

Poet, essayist and editor Kevin Young is the second director of the Smithsonian's National Museum of African American History and Culture. He joins Kojo to talk about his vision for the museum and how it can help us make sense of this moment in history.

Ms. Woodruff joins us to talk about her successful career in broadcasting, how the field of journalism has changed over the decades and why she chose to make D.C. home.