Saying Goodbye To The Kojo Nnamdi Show

On this last episode, we look back on 23 years of joyous, difficult and always informative conversation.

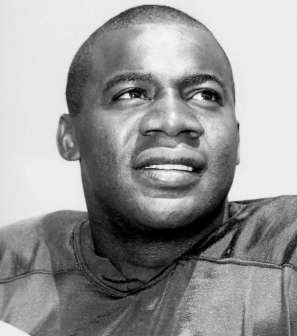

Willie Wood Sr. played with the Green Bay Packers from 1960 to 1971

D.C. native William Vernell Wood Sr. was passed over in the 1960 NFL draft, but he went on to forge a career as one of the greatest defensive backs in the history of professional football.

Before he retired, he won five NFL titles and two Super Bowl championships with the Green Bay Packers, where he played safety from 1960 to 1971.

He was named to the Associated Press All-Pro Team five times and played in the Pro Bowl eight times.

Wood was named to the NFL’s 1960s All-Decade Team and chosen for the Super Bowl Silver Anniversary Team in 1990.

He was inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1989. And went on to coach in the NFL, WFL and CFL.

Willie Wood Sr. passed away at an assisted living facility in Washington, D.C. on February 3, 2020. He was 83.

Produced by Monna Kashfi

KOJO NNAMDIWelcome back. NFL football legend and D.C. native, William Vernell Wood, Sr. was overlooking in the 1960 draft, but went on to forget a career as one of the greatest defensive backs in the history of professional football. In all, he won five NFL titles and two Super Bowl championships with the Green Bay Packers, where he played safety from 1960 to 1971. He was named to the Associated Press All-Pro Team five times, played in the Pro Bowl eight times.

KOJO NNAMDIWillie Wood was named to the NFL's 1960s All-Decade Team and chosen for the Super Bowl Silver Anniversary Team in 1990. He was inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1989, and went on to coach in both the NFL and the CFL. Willie Wood passed away at an assisted living facility here in Washington on February 3rd. He was 83. Joining me now to remember his legacy is his son, Willie Wood, Jr., himself a former arena football league player and coach and, as we said, the son of Willie Wood, Sr. Good to see you again.

WILLIAM WOODWell, thank you for having me. I appreciate it.

NNAMDIYour father was not selected in the 1960 NFL draft after playing college football for the University of Southern California. How did he end up as a central figure in Vince Lombardi's Packers dynasty?

WOODWell, the story he always told, and a lot of his teammates at the time kind of verified the story, he actually wrote letters to Vince Lombardi. Not just him, other teams, but Vince was the only one that kind of responded. And I think what people tend to forget is, at Southern Cal, he played both ways. So, you know, switching from quarterback to defensive back wasn't that big a deal for him. And he also kicked. People don't realize that he was one of the backup kickers for a few years with the Packers.

NNAMDIHe was an amazing man and an amazing player. As a matter of fact, somebody wrote that Lombardi made two wise decisions in a career full of them. He answered Willie Wood's letter, and he moved him to free safety. (laugh)

WOOD(laugh) Well, that's actually what Herb Adderley just told me last week, when I spoke with him. He said, you know, Willie saved me so many times. He said, I would look over at your dad and I would say, Willie, the next pass, I'm going to jump it, so you got my back. And he said dad would look at him and say, yeah, just don't miss. (laugh) So, yeah, we hear those stories all the time, straight from the horse's mouth.

NNAMDIYour father did not have the height or physique of many of his peers on the field, but he took down players who outweighed him by 40 pounds. What was his approach to the game? I know I saw one photo where he had such a high vertical leap, that I saw in this photo. A whole bunch of players were jumping, and he was, like, a foot-and-a-half above the rest of them, even though he was only, what, 5'10", 5'9"?

WOODYeah, he was about 5'10". I think he played at about 190, at his heaviest. But he was an amazing athlete, basketball, dunked the ball well into his 40s, which was embarrassing to me because, you know. (laugh) But when it came to tackling and toughness, it was inside of him. He wasn't afraid to mix it up with anybody, no matter how big, small. It didn't matter. He just had toughness.

NNAMDIMost importantly, during the off-season Willie Wood would return to D.C. and teach, where he taught junior high school, and asked the city government to allow him to mediate disputes between rival gangs. Why was he so caring and invested in the District's young people?

WOODWell, I mean, those who grew up with him or around his era know that the city itself was in his blood and in his DNA. So, the community and its survival was important to him. And so, naturally, that begins with the children. And, of course, number two, Boys Club was at the heart of all that for him. And, you know, what people of this era don't realize is that, you know, professional football players back then had the work other jobs during the off-season, because...

NNAMDIExactly right. That's why he taught high school.

WOOD...there was no signing bonuses and no huge contracts. So, he had to work. And that was close to his heart, you know, the kids, the children.

NNAMDISpeaking of which, what kind of father was he?

WOODHe was -- you know, friends would ask, wow, what's it like living with a Hall of Famer? And I would tell them, man, he makes me take out the trash, and (laugh) I was in trouble if my grades were bad which, you know, sometimes was often. You know, he was a hardcore dad with a lot of love. I mean, he wasn't an outward hugger and “I love you son” and those types of things, but you knew that he loved you. And my brother and sister said the same thing. You knew where he stood.

NNAMDII knew you loved him, too, because when I met him later in life, you used to be around him a lot (unintelligible) .

WOOD(overlapping) Yeah, as an adult, we became hanging buddies.

NNAMDIThat's right. Your father made history in his coaching career, as well. He was the first African American head coach in professional football in the modern era when he coached the Philadelphia Bell in the WFL in 1975. What did his coaching career mean to him?

WOODWell, you know, the biggest thing for him was, you know, what was -- he was a door-opener. And how many of us can say that we were the first to do one thing? He was the first to do, I don't know, four different things. So, being the first black head coach in modern football was important to him, just so the world could see that it didn't matter. It didn't matter, you know. And when he got fired, later on in Canada, he joked about how, well, now they know they can also fire black head coaches, too. (laugh) You know, it's not the end of the world, you know. We can do both. We're just coaches.

NNAMDIHow did his playing and coaching career inspire your own playing and coaching career?

WOODYou know, the cool thing was, is that with my brother and I, in terms of football, he never pushed us. He never said, hey, this is what the family does. This is what you're going to do. But when you grow up with it kind of in your blood and you see it every day, it's like, what else are you going to do?

WOODMy brother and I never worried about trying to match his accomplishments, because Hall of Fame is unmatchable. You know, nobody's going to do that. And we obviously played in different eras, but it just inspired me to enjoy the game, because he loved it. You know, he loved it.

NNAMDILived it and loved it.

WOODYes.

NNAMDIHere's Marcus in Silver Spring, Maryland. Marcus, you're on the air. Go ahead, please.

MARCUSHello, Kojo, and hello Mr. Wood. How are you both today?

NNAMDIWe're both well.

WOODFine. Thank you, Marcus.

MARCUSGood. Sir, I just wanted to say, I went to the University of Southern California, as well. And I was lucky enough to walk onto the football program there. I'm from Maryland, but I went to school out in California. And I've got to say, Willie Wood was sort of an inspiration for us (unintelligible), myself being undersized, as well. And I remember constantly thinking about him and how prolific he was as a football player.

MARCUSAnd being an African American, I mean, just realize what he would've had to go through at the time, in Los Angeles, in the '50s, of being USC's first black quarterback. That's not really talked about much. He was the first black quarterback at USC, so he was a trailblazer, in many ways. And, you know, I'm sorry I didn't get to meet him. I really would've liked to meet him. But, you know, he is remembered. He is well-remembered.

NNAMDIWell, thank you very much for your call.

WOODThank you. Great words. Great words.

NNAMDIBefore the end of this broadcast, we'll tell you how, even though you didn't meet him, you can still be in his company. (laugh) We'll talk about that.

WOODYou know, can I speak to what he was talking about?

NNAMDIYes.

WOODWhen he first went to California he went to Coalinga, which is now called West Hills College. It was a junior college. He had to play there for a year. And you talk about how they treated blacks. Well, they had a main street where he wasn't allowed to go to any of the restaurants, the stores or the hotels or anything. So, he took that junior college to their first-ever national championship. And then do you know they had a parade for him down that same street, (laugh) where he couldn't use any of the stores or anything?

NNAMDIHe was a pioneer.

WOODYeah, absolutely.

NNAMDIWillie Wood played 166 consecutive games for the Packers, but he was plagued by injuries during his career, many quite serious. And, in retirement, he underwent several major surgeries. He once told a reporter that, quoting here, "like a lot of other players, I was dealt a bad hand." He also developed some dementia and Alzheimer's in his final years. Did his physical pain and the cognitive repercussions of being a professional football player, did those things weigh heavily on him in his later years?

WOODIt did, you know, because he was looking forward to being fully retired and actually traveling the country being a celebrity and a Hall of Famer and playing golf. And the physical ailments prevented him from doing that way before -- or just before the dementia kind of took over. He had a hip replacement. He had two knee replacements, on the same knee. And while he was rehabilitating, that is when the dementia stepped in. So, he never got a chance to enjoy that. And he was always disappointed about that.

NNAMDII got to know him in his later years and considered him a friend, but there have been dozens of remembrances written about your father in the past week and statements across the NFL. How would you like him to be remembered?

WOODThe accomplishments he did as an African American, I think, stand out to me. Being the first black quarterback, not just at USC, but in the Pac-10 Conference, the first black head coach in modern American football and the first black head coach in the CFL. That's four times he was the first man through the door. I mean, if anybody needs to think about what it takes to have that kind of courage, to do it over and over again through your entire adult life, those are the things that stand out. I mean, I think that any great athlete could maybe accomplish half of the things he did, but it takes a special kind of man to be the first one through the door.

NNAMDIIt certainly does. Will there be a public memorial service here in D.C.? Tell us when and where.

WOODYes. Well, his funeral service, the viewing will be on Wednesday, February 19th at Bible Way. The viewing is from 9:00 a.m. to 11:00. The funeral services will be at 11:00 a.m.

NNAMDIThat's October 19th...

WOODNo, no, February 19th.

NNAMDIFebruary 19th. Why was I thinking October? (laugh) February 19th at Bible Way Church, which is, of course, at the intersection of New Jersey and New York Avenues here in Washington, D.C. Willie Wood, Jr., thank you so much for joining us.

WOODWell, thank you for having me. It's my favorite topic.

NNAMDIWillie Wood, Jr.'s a former arena football league player and a coach and the son of NFL Hall of Famer Willie Wood, Sr. We're going to take a short break. When we come back, you'll meet some young people who are pushing D.C. to have a state mammal. I'm Kojo Nnamdi.

On this last episode, we look back on 23 years of joyous, difficult and always informative conversation.

Kojo talks with author Briana Thomas about her book “Black Broadway In Washington D.C.,” and the District’s rich Black history.

Poet, essayist and editor Kevin Young is the second director of the Smithsonian's National Museum of African American History and Culture. He joins Kojo to talk about his vision for the museum and how it can help us make sense of this moment in history.

Ms. Woodruff joins us to talk about her successful career in broadcasting, how the field of journalism has changed over the decades and why she chose to make D.C. home.