Saying Goodbye To The Kojo Nnamdi Show

On this last episode, we look back on 23 years of joyous, difficult and always informative conversation.

Guest Host: Jen Golbeck

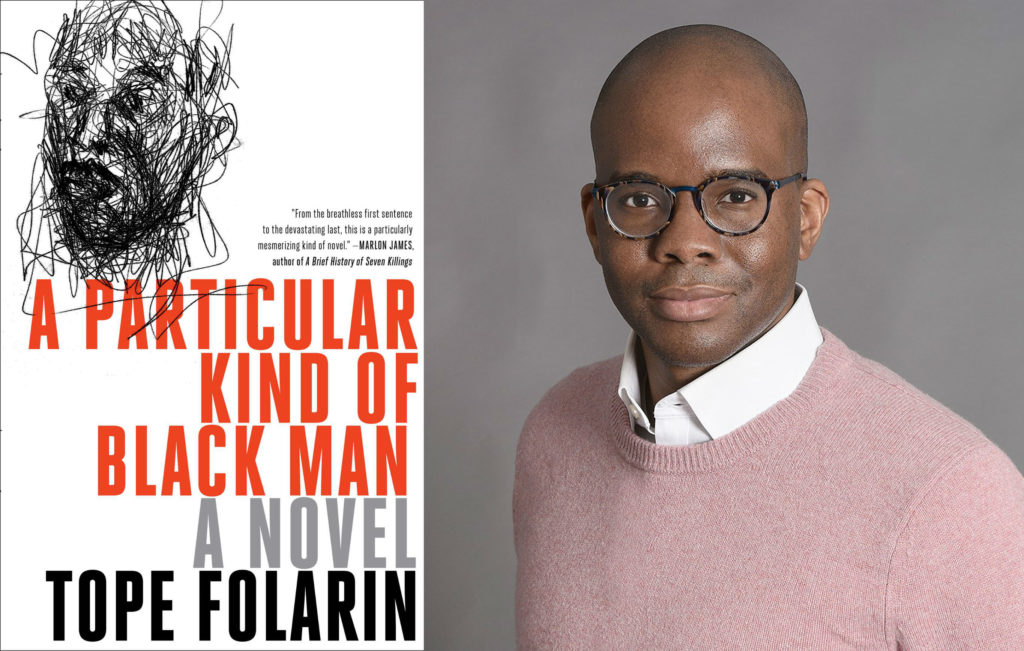

Tope Folarin's debut novel follows the early life of Tunde Akinola, a Nigerian American.

After finishing his academic career as a Rhodes scholar and starting a professional career at Google in London, Tope Folarin quit his job and moved to Washington, D.C. to become a writer. He was looking for a city amenable to artists: free museums, a strong theater scene and a manageable cost of living. Folarin spent his time attending readings and copying from books he couldn’t afford at Politics and Prose. He landed a fellowship at the Institute for Policy Studies, then a job at the Local Initiatives Support Corporation, all while keeping up his nightly writing practice.

In 2013, Folarin won the Caine Prize for African Writing for his short story “Miracle.” This month, Folarin released his debut novel. “A Particular Kind of Black Man” follows the coming-of-age of Tunde Akinola, a young Nigerian American, as he wrestles with his cultural identity.

Folarin sits down with Kojo to talk about Tunde’s journey, his own path as a writer and D.C.’s literary scene.

Produced by Cydney Grannan

JEN GOLBECKTope Folarin's debut novel is the coming-of-age-tale of a young Nigerian American, Tunde Akinola. Did I say it right? His home life is tumultuous. Poverty, mental illness and racism shake his family. Tunde's internal life is also chaotic, as he tries to navigate his identity. Is he Nigerian? American? Black? Some of these questions are ones that the author himself has had to wrestle with. Joining me now to talk about his book and his career is Tope Folarin. He is the author of 'A Particular King of Black Man,' which is out now. Tope, it's good to have you here.

TOPE FOLARINIt's so good to be here.

GOLBECKOkay. Tell me how to say your character's name the right way.

FOLARINTuned Akinola.

GOLBECKOkay. I'm going to work on it.

FOLARINYou did pretty well. You did pretty well.

GOLBECKSo, like the main character of this novel, you're Nigerian American, and grew up in Utah and Texas.

FOLARINYeah.

GOLBECKTell us about your childhood and your career before you became a writer.

FOLARINSure. Like you said, I was born in Utah, in a place called Ogden. We lived in Utah for about 13 years, and then we moved to Texas. We moved around Texas for a bit, and I ended up going to high school in Arlington, Texas, which is where the Cowboys play. Maybe I shouldn't mention that in D.C., but it is what it is. Afterwards, I went to Morehouse College in Atlanta, Georgia. Spent a year at Bates College in Maine, and some time at the University of Cape Town in South Africa, as well. After that, I was at Oxford, where I was a Rhodes Scholar. I was there for two years. And then I started working with Google. And that's when my story kind of takes a turn, because it was -- at Google, for me, it seemed to be the kind of perfect job I'd always wanted. I was traveling around the world, doing really exciting work. But I couldn't shake this kind of desire, this impulse to write, to be creative. And it was infiltrating every part of my life. And so that's when, for me, the journey as an artist began.

GOLBECKSo, I'm a professor in my life when I'm not sitting in for Kojo. So, I'm always interested in people's academic journeys. Morehouse has always been fascinating to me. It's obviously not a university that I would have gone to. Tell me about your time there, a little bit.

FOLARINIt was -- I'm really, really glad I went to Morehouse. I went to Morehouse partly because I'm one of those kids who grew up -- so, when I was younger, my father used to watch this show called “I Spy,” which featured Bill Cosby and Robert Culp, and Bill Cosby played a Rhodes Scholar on that show. And my father was completely enamored with the show, and, too, with the notion that there was a black person who was, like, the smarter one of the duo. He just was fascinated by this. And he would often tell my siblings and me that we could, you know, too, achieve great things. And so, I became enamored with the show. And then we watched “The Cosby Show.” And then “A Different World” came on. And I remember when it premiered, because I just was so incredibly excited about this show. It's a show that featured, you know, people of color having all these incredible discussions about events of the day, and they were all very attractive. And I wanted to go to Hillman very badly. And so I did my research and discovered that the show was filmed on the campus of Spellman and Morehouse. And so when I was about seven or eight, I became fixated on the idea of going to Morehouse.

FOLARINLong way of saying that, by the time I got there, it didn't quite -- at least initially -- align with what I thought it would be. I wasn't fully prepared for for the class dimension of going to a place like Morehouse.

GOLBECKInteresting.

FOLARINYeah. There a number of people at Morehouse who emerge from sort of generations of black sort wealth, and I wasn't fully prepared for that. But on the other end of it, I had a tremendous experience. I always say that I met the brightest people I've ever met in my entire life at Morehouse. And that's including my entire academic career. And many of them are doing tremendous things in the city, around the country and around the world. And so it was just kind of liberating to be in a space where it wasn't about my identity or who I was or where I come from. It was really about sort of doing the best on the test. And I love -- I'm very competitive, and so I think I really thrived in that environment. So, it was wonderful for me.

GOLBECKThat's so interesting. I had exactly that same reaction to a show as a kid growing up. Obviously, like, I'm a white girl, right? So, it didn't have that same dimension for me. But growing up in a place where -- I would say academics weren't valued in the same way as I certainly value them in my life now. Like, there's this whole cool intellectual space that you can be in and be awesome. Like, I had that same feeling about it.

FOLARINSure.

GOLBECKOkay, so, I heard that Oprah Winfrey paid for your last year at Morehouse. You want to tell that story?

FOLARINWell, so, I was in a bad way financially during my last. I mentioned before that I spent some time traveling. And by the time I returned to Morehouse, even though I had filed all the necessary paperwork, for some reason, I had lost my scholarship. I was on a full scholarship to Morehouse. And so when I came back, I was kind of bereft. I was living on my friends' floors, and I was told that I wouldn't be able to finish my senior year. And I was just sort of really traumatized by that, because I was doing well, academically. And I had these dreams of sort of walking across the stage. You know, I'm the oldest kid in my family, and sort of making my parents proud, and all that came crashing down. And so I started this campaign. I just wrote a bunch really prominent African Americans and kind of laid out my story, not expecting that anything would happen. So, I write a letter to Oprah, and she's somebody I've admired for a very long time. Two weeks later, I was called into the kind of administrative building at Morehouse, and they said that Oprah had covered my entire senior year.

GOLBECKWow.

FOLARINIt was as if I had stepped into some other dimension. It was just that fantastical.

GOLBECKIt is. Like, that's a miracle story.

FOLARINYeah. It was pretty incredible. And I was shocked by it. And then the story gets even better, because three months later, I had just won the Rhodes Scholarship, and Oprah was coming down to Morehouse, because they were celebrating her for the fact that she had done this for a number of students. And so I had, you know, they sat me at the same table as her. And we had this really wonderful conversation about my travels and about her life and everything else. And she was very gracious and warm. And then the day I graduated, I opened up my mailbox, and there was a handwritten note from Oprah, and she said, I enjoyed speaking -- and this was, you know, probably about three months later.

GOLBECKWow.

FOLARINAnd she said, you know, I enjoyed speaking with you. And I think you're great, and I'm excited about your future. And so I think even more than, you know, the fact that she paid for my senior year, I was so shocked by the fact that she continued and engaged with me after she had provided me with this wonderful gift. So, I'm incredibly blessed, and I recognize that.

GOLBECKThat's amazing. Did you send her a copy of your book?

FOLARINI have. She has a copy.

GOLBECKThat's great. We'd love for you to also join the conversation. Are you part of the local writing community here in D.C.? Tell us how the community has helped your writing. You can give us a call at 1-800-433-8850. You can send us a tweet to @kojoshow, or send us an email to kojo@wamu.org. Okay, so, you went all over the place.

FOLARINYeah.

GOLBECKAnd now you're here in D.C. How did you get here?

FOLARINYeah. The story about coming to D.C. So, I was in my second year at Google, and I was actually -- again, I was, at least ostensibly, having this great time. I was spending a lot of time in Israel and Turkey. And it was actually on a flight to Istanbul. Part of my responsibility was to talk with government officials about sort of tech policy, to kind of convince them that, you know, Google wasn't intrinsically bad, and that sort of open internet was a good thing. And so I was on one of these trips to Istanbul to speak with government officials, and I'd spent the night before the flight, like, writing, you know, something. And, on the plane, I was seized by this idea, so I was writing on the entire plane from London to Istanbul. And the person seated next to me kind of interrupted me at the end, and he said, whatever you're doing with that much passion is what you should be spending your life doing.

GOLBECKWow.

FOLARINAnd that, for me, was a profound moment, because I recognized he was right. And so, a couple of months later, I got a bonus, and I used that as an impetus to come. And I thought, I really wanted to move back to the States. But, for me, the question was where can I move in the States that would be in some ways similar to London? Which is to say a place that had free museums, you know, public lectures, the kind of place that could foster this kind of burgeoning artistic sensibility that I had. And, you know, I thought of a lot of cities. I thought about maybe Chicago or Los Angeles or New York. And, in the end, D.C. just made the most sense, because to the wonderful network of free museums here, public lectures...

GOLBECKSure, yeah.

FOLARIN...the robust writing community and sort of thriving independent bookshop scene, as well. And so, for me, D.C. made the most sense. And I came, in 2008, just about three months before the great recession. And so I was basically -- I didn't work for about a year and a half after I left Google. And I was very upset about that, at the time. But that also a time when I was able to do a lot of the kind of soul-searching and research that kind of led to me writing this book. So, I'm deeply grateful for that.

GOLBECKSo, what's the writing community like in D.C.? Who are some of the people that have guided you since you came here?

FOLARINYeah. There are a number of people. And so one person who comes to mind is Marita Golden. She started this organization called the Hurston/Wright Foundation. And it's a wonderful organization that supports writers of color. And that was the first kind of institution that said that you are a writer. Maybe there's something that you're writing that is worthy of being published. And so, I went to my first workshop back in 2012 that was facilitated by a writer called Dolen Perkins-Valdez, who is also a local writer who has a great reputation. And it was really affirming to be in a space where there were other writers who were just trying to make it. And, you know, having an instructor who was accessible and who lived in D.C. who had published, was deeply meaningful. And Marita Golden has also been very accessible and a wonderful presence for me in my life. Ethelbert Miller is somebody else who comes to mind. He's a wonderful, wonderful human being and I'm sure many of your listeners know him really, really well.

GOLBECKYeah, an institution.

FOLARINYeah. He absolutely is. And I was somewhat nervous about meeting him, because I had read his poetry beforehand. And I was a fellow at the Institute for Policy Studies, which is a great think tank here in town. I currently chair the board, but back then, I was just a fellow. And I kind of approached him very kind of nervously, and, you know, said I was a writer, and he said he would evaluate some of my work. And he sent me back my work, and it was all marked up, and I didn't like him for a couple of days. But then I recognized that he was probably right. And so we had this back-and-forth. And then there was sort of other institutions. One writer I deeply admire is Edward P. Jones. I read “The Lost World” so many times, and his other books, as well. And so it was meaningful for me, too, to come to this city and kind of track down of the streets and the places that he talks about in that book, just because I read that book so many times. So, yeah, I just feel I've been embraced by this community of great writers in D.C., and they've been mentors.

FOLARINThey have picked up the phone late at night, you know, when I'm having some kind of crisis. They're all wonderful human beings, and I'm deeply grateful to them.

GOLBECKYou won the Caine Prize for African Writing in 2013, for your short story “Miracle,” which is a beautiful piece of writing.

FOLARINThank you so much.

GOLBECKAnd, notably, you were the first person outside Africa to win that prize. So, why was winning that a really pivotal moment for your writing career?

FOLARINYeah. It was for a couple of reasons. One, the Caine Prize has a kind of international reach, and so when I won, I had an opportunity to travel around Europe and Africa and the States, as well. And so I won it for the first story I had published, “Miracle.” And I published this story about maybe six or seven months before I won. And so it was really like going from zero to 100. I was like in some kind of sports car. And, you know, I went from being completely anonymous to fielding questions on stages with, you know, writers I had admired for years and years and years. So, that was really sort of fascinating. The other component of that, too, was that it was another opportunity to kind of have conversations about identity. As you mentioned, I was the first person born outside of Africa to win the Caine Prize. So, even when I was on the short list, people were asking, like, ehy is this person on the short list? One clause of the prize says that if one of your parents was born in Africa, that you're eligible for the prize. So, the prize has room for diasporic Africans, as we're often called. And so I fit -- I kind of qualified, under that clause. But it really kind of -- my presence on the short list, I think, prompted all these conversations about who is an African.

FOLARINAnd I think I was prepared for those conversations, because I've been grappling with these questions my entire life, and indeed, my novel is about these questions. And so it prepared me for this kind of -- my novel coming out and having to answer these questions now. And examining myself, as well, and determining where I fit, and who I actually am.

GOLBECKIt's interesting. I mean, to have those moments in your life, where it's, like, this is the day this thing happened, and it's a very clear separator of the life before and the life after.

FOLARINIt's a wonderful way of putting it. Yeah. And that's exactly what happened. You know, the other great thing about the Caine Prize is that I remember quite vividly the award ceremony in Oxford. And so you're sitting at a table -- it's a kind of miniature version what we're all accustomed to seeing on television, you know, when somebody wins a prize. And they announce the winner, and then, all of a sudden, there's a scrum of reporters that kind of accost me. You know, they're asking questions. And, you know, of course, the question on everyone's kind of lips is, you know, are you actually an African? Talk to us about your identity. And, yeah, that was a kind of dividing line, because before, I had been just kind of an anonymous, you know, writer, and now I was, you know, answering these questions about African and America and writing and being a creative person and all kinds of things. So, yeah, it was definitely a dividing line in my life.

GOLBECKSo, let me see if I can formulate this question off the top of my head. I have also had one of those moments, which is not with writing, but with something else that I do, where it's, like, okay, like this day, all of a sudden, the doors all opened. And there's this real moment. And what I found since then, for myself, is that I have all these opportunities, and it's great. But also, I was that person who was just able to say yes to everything before that. And now I can't, and it feels a little bit weird, because I want to be that person who's connected to all the people around me. Like, yes, of course, I can help you. I can talk to you about this. And now there's so many of those people, that I have to pick and choose, and it feels a little bad. And I'm wondering, you know, as someone who's like -- you immersed yourself in this community, but yet you also had these high profile mentors helping you. How do you navigate what probably has been a really changing role for you, too, as your profile has suddenly skyrocketed?

FOLARINThat's a really great question, and something I was just sort of thinking about last night, actually. Because it's important for me to kind of serve as a mentor and to help people who are trying to find their way, I'm really, really sort of pleased that I live in D.C. and that I have access to, you know, sort of emerging writers and established writers. And I want to be a good literary citizen. But it is difficult, especially during this moment. I have a few emails in my inbox that I haven't responded to that are important to me, and I do want to respond to. But, you know, I'm in the midst of a book tour, and I have a very rambunctious two-year-old who kept me up last night. And, you know, life is really sort of fascinating right now. So, I'm committed to it, especially because I'm still smarting from a couple of those people I reached out to who didn't have -- you know, didn't reach back out to me. And so, you know, I don't want to be in that position, as well. And so, yeah, it's something I'm still grappling with, and I hope that I figure out some way of doing it well.

GOLBECKIf it makes you feel any better, I also have a lot of those emails. I feel like the important ones are the ones that always linger the longest, because you really want to take the time to answer them. Right?

FOLARINThat's exactly it. Yeah, yeah.

GOLBECKWe're going to take a quick break. And then we'll be back with more conversation. Stay tuned.

GOLBECKWelcome back to The Kojo Nnamdi Show. This is Jen Golbeck, sitting in for Kojo, and I'm talking with Tope Folarin about his new novel, “A Particular Kind of Black Man.” So, Tope, tell us about your new novel. When did you start writing it, and what has your process been?

FOLARINYeah. I started writing it probably, I'd say, 2010. And I started writing it when I was a fellow at the Institute for Policy Studies. And, at the beginning, I didn't quite know what I was writing. I just had this impulse to write, and so I just started writing. And, at the beginning, I was writing a story that was more explicitly autobiographical. And so that's the way it began. And as I continued, I discovered -- you know, I used to be one of these people who rolled my eyes whenever writers spoke about, like, characters speaking to them. I'd say, okay, here we go, the mystical mumbo-jumbo nonsense. But about three months into writing this, that began to happen to me. And I had this kind of deep sense that the character I was writing about wasn't me, that it was somebody else who had his own path and his own story to tell. And so I began to follow that line, and ended up with this novel today.

GOLBECKSo, I'd like you to talk a little bit more about what of your own experience did you draw on for that character. And if it's easy to talk about, like, where did you really see that divergence?

FOLARINYeah. So, I drew -- anybody who reads the book and a sense of my biography will see that there are certainly some similarities. We've already pointed out some of them. I was born in Utah. Tunde, as well. Tunde goes to Morehouse. I did, as well. That kind of thing. But I think the difference is in some of the decisions that Tunde makes that are quite different. In actuality, Tunde comes to a sense of who he is much quicker than I did. He comes to that sense when he's in college. I didn't get there till I was in grad school. And so a lot of his pathway to self-discovery is accelerated for that reason. I think, in some ways, he's more kind of aware of the world than I was when I was coming up. And so I think the divergence occurred, again, when I revising. And just, you know, I was trying to kind of insert more and more of my life into the text, and the text wouldn't take it. The prose wasn't working out. And so, once I allowed the character to kind of go in his own direction, I noticed the novel began to sing a little bit.

GOLBECKWe'd like you to join the conversation, as well. Do you balance multiple cultural identities, and did you do that growing up? And how do you manage them now? You can give us a call at 1-800-433-8850. So, adolescence is a time when everybody is struggling to figure out who they are and how they fit in the world. As Tunde is growing up, he's being pulled in different directions. He worries he's not black enough or American enough or Nigerian enough. How does he navigate those identities?

FOLARINIt's very very difficult for him to do so. I think the thing that is most difficult for Tunde is that he is -- his parents are from Nigeria. He's growing up in a predominantly white environment. And so people assume that he's an African American, but he doesn't have sense of the African American experience. And so that is very difficult for him, and his parents are pulling him in one direction. They're saying to him, hey, you're Nigerian. And when he's at home they treat him like he's a Nigerian. He listens to Nigerian music. He eats Nigerian food. But outside, he's treated as someone else. And so he has no sense. And I think the thing that's most difficult in adolescence is that you're just trying to fit in. The question becomes where do you fit in if none of these identities quite fit? The book is really about trying to come up with a sense of self that makes sense, constructing identity, which is something that I think that we're all doing in the 21st century. We're all engaging the act of constructing an identity, whether it's an online profile, or you're online presence, in general. We're all kind of actively participating in the act of constructing identities. And two, outside, in the kind of real world, if you will, we're all sort of consciously saying, you know, even if we were born with a particular identity or, you know, we're born with a particular gender, we're saying, you know, this is who I actually am, and claiming that. And so I think the book, in many ways, embraces that path and says that is something that all human beings, perhaps, have to do.

GOLBECKSome of the most captivating moments in the book are when Tunde is around black people outside of this family. And, at first, it's something he craves, he looks forward to. But by the time he gets to college, he seems to have a more critical view of the black friend group that he makes. So, what's his experience like with black friendships?

FOLARINIt's a really great question. I think that Tunde, again, doesn't know much about African Americans, and he's -- much of his perspective about the African American experience comes from his parents, who, like African immigrants, are somewhat critical of African Americans. I grew up in a household in which one of the storylines about African Americans was that they weren't working hard enough. And I've since come to discover that actually not a really good narrative. But for many Africans, that was their kind of relationship with African Americans. It was this kind of contentious relationship between both groups. And so I think Tunde inherits that. Part of it, too, is that he is not -- because there's all this stuff that's happening within him, and he's struggling to figure out who he is, that he's kind of externalizing some of that. If he meets somebody who is proud of who they are and celebrates their music and culture, there's a part of him that's deeply jealous of that experience. And so part of what -- he's also projecting, as well. And he's doing that. I'm sure if you could corner him, he would very much like to be a kind of accepted member of this community. But he knows that there's something about him that's different, and he's grappling with that.

GOLBECKSo, let me seize on the music thing...

FOLARINYeah, of course.

GOLBECK...that you just brought up, because the novel is full of musical references, and we've been grabbing onto some of them for the music in the show today. But the novel has both Nigerian artists and American ones. And when Tunde and his family move to Texas, his father gives his a clock radio, so that he can get up for school on his own. And that was such an interesting thing to read in the book about him listening to and discovering that music. So, I'd like you to read a passage from this section, which you should have in front of you. Where we're starting, Tunde is hearing the song “Thank you,” from Boyz II Men, for the first time. Is there anything you want to add before I ask you to read?

FOLARINNo. Well, I guess one thing I'd add is that this is him kind of being exposed to art in a visceral way for the first time. So, this is why this is such a deeply meaningful experience for him. The passage goes: The song startled you. Excited you. Overwhelmed you. You couldn't recognize the various elements of it. The doo-wop, New Jack swing, the soul. And yet it was, without a doubt, the most beautiful you had ever heard. During your first few days in Texas, you fell Boyz II Men, Mariah Carey, Erin Hall, Whitney Houston and Michael Jackson. Every night, after you and your brothers prayed, you would flick on the clock radio, close your eyes and listen. You studied the tunes that emerged from that cheap clock radio harder than anything you were supposed to studying in school. Soon, you had many melodies to accompany your dreams. You no longer needed to create your own personal lullabies. Sometimes, when you were listening, time seemed to stop and accelerate, simultaneously. Sometimes, the music embraced you and caused you to forget where you were, who you were. Sometimes, you felt the music had created you, so you could acknowledge its exist.

GOLBECKTalk more about the role that music plays in Tunde's life. That gives us a good kind of discovery moment. But beyond that.

FOLARINIt's a space where -- you know, maybe it's the one space where he can be fully himself, because when he's listening to music, it's really a matter of the way he's responding emotionally to that music. And I think that becomes very, very important for him, because it's this space where, one, he's discovering what makes him excited, what makes him happy, what makes him joyful. And there isn't any kind of critic of that. It's just him having this kind of really deep connection with art. And I think that's, in many ways, if we're going to talk about sort of the autobiographical content of this novel, I had a similar experience in terms of my kind of interaction with art. And so, for Tunde, this is space where he begins to discover who he is via this kind of his listening to music.

GOLBECKHow does Tunde learn about and deal with racism in the book?

FOLARINYeah. I think many, many, many ways. My novel is called “A Particular Kind of Black Man,” and I think he comes up with the sense that he inherits from his father that he has to be a kind of particular kind of black man, in order to be successful. His father cites people like Sidney Poitier as, you know, the kind of sort of standard that he live up to. And his father's sense is that in order to be successful as a black person in this country, your entire kind of being and identity has to be about placating others, making others accept you. And so that's the kind of identity he constructs for himself, and that is a vast stage of racism, this notion that you can't be fully who you are, but you have to construct a self to satisfy others, because that's what Tunde does. And the reason why he has a crisis later on in the novel is because he gets to a point where he says: who am I, actually? Not, you know, not this person I've constructed to satisfy and please everyone else. Who am I? And that's, I think, a journey that many people in this country who are of color, or women, and other marginalized communities have experienced in their own lives.

GOLBECKYeah. I mean, as you were saying that, I was like, well, that sounds very familiar. Even though, you know, I have not dealt on it on the race side, I obviously have as a woman. And that core experience is, I think, so universal. But interesting to see it expanded beyond our own lives.

FOLARINYeah.

GOLBECKSo, partway through the book, you change how Tunde's narrating. Can you explain how the narration changes, and why you decided to change it?

FOLARINAbsolutely. So, part of what happens in the novel is that, as I said before, Tunde is writing this because he's at a crisis point. Part of the reason he's writing this is because he has a sense that his memories maybe are betraying him in some way, that he can't trust his own personal history. And there's a point in the novel where he kind of confronts that. And he gets to this point where he says, you know, I can trust my memories. So, that's something that literally happens in the novel. But I also was trying to -- kind of reaching for a metaphor, which is if you have constructed this identity that is about placating others and making sure that others accept you, the question becomes: how much of your past can you truly accept? How much of your past is real? And that's something that he confronts in the book. His memories have all been geared towards constructing this persona that can satisfy others. And so when he questions himself, he also questions his past. And it provides him with a platform to begin to build a future for himself that isn't predicated on some of these things we've just discussed.

GOLBECKTope Folarin's new book is “A Particular Kind of Black Man.” The Institute for Policy Studies and Busboys and Poets are hosting a book release party for Tope Folarin Tuesday, September 3rd, at the Busboys's K Street location. Ethelbert Miller will be hosting the Q&A. So, we'll post more information about that. And that's it for the show today. Our conversation with Tope Folarin was produced by Cydney Grannan, and our segment about ICE check-ins was produced by Mark Gunnery. Coming up tomorrow, congratulations Arlington and Alexandria, you now have the most competitive housing markets in the country. We'll talk about what that means for affordability in the region. Plus, are you ready for a new fall wardrobe? Have you thought about thrifting? You'll want to tune in for tomorrow's show before you shop till you drop. That's tomorrow, at noon. Thanks for listening.

On this last episode, we look back on 23 years of joyous, difficult and always informative conversation.

Kojo talks with author Briana Thomas about her book “Black Broadway In Washington D.C.,” and the District’s rich Black history.

Poet, essayist and editor Kevin Young is the second director of the Smithsonian's National Museum of African American History and Culture. He joins Kojo to talk about his vision for the museum and how it can help us make sense of this moment in history.

Ms. Woodruff joins us to talk about her successful career in broadcasting, how the field of journalism has changed over the decades and why she chose to make D.C. home.