Saying Goodbye To The Kojo Nnamdi Show

On this last episode, we look back on 23 years of joyous, difficult and always informative conversation.

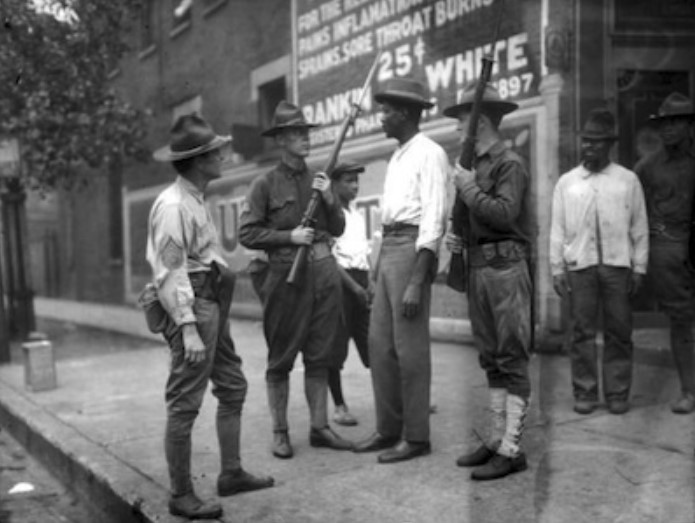

Three armed soldiers question an unidentified African American man in D.C. during the 1919 race riots.

Weeks of media hysteria. Hundreds of black men arrested. 500 guns sold in one day. A riot. As many as 39 people dead and 150 injured.

The race riot that took place in the District from July 19 to July 24, 1919 — one of a series of race riots that unfolded across the country in what came to be known as the Red Summer — is a chapter of the city’s history that is not taught in most history books. But some historians say that even though the riots did not lead to immediate change in D.C., the riots momentarily united the African American community in the District — a community that had long been divided by class and economic status. And the events of the Red Summer laid the foundation across the country for the integration of American troops during WWII.

We’ll learn more about the events that led to the race riots of 1919 in D.C., and the role that the military and the media played in heightening tensions during a summer of unrest.

Produced by Monna Kashfi

KOJO NNAMDIYou're tuned in to The Kojo Nnamdi Show on the WAMU 88.5. Welcome. Later in the broadcast a new program teaching entrepreneurship at Georgetown University seeks to provide former inmates with better employment opportunities. But first this week marks the 100 year anniversary of the 1919 Race Riots in Washington, D.C. The five days of violence that unfolded in the District from July 19 to July 24th 1919 were preceded by weeks of media hysteria.

KOJO NNAMDIOnce the dust had cleared as many as 39 people were dead and hundreds of black men had been arrested often without just cause. And it all came to an end because of a typical D.C. summer downpour. Joining me to discuss this little known chapter of the city's racial history is Alan Spears. He is the Cultural Resources Director at the National Parks Conversation Association. Alan Spears, thank you for joining us.

ALAN SPEARSIt's my pleasure, Kojo. Thank you for having me.

NNAMDIAlso with us is Rawn James Jr. He is an Attorney and Author of "The Double V: How Wars, Protest, and Harry Truman Desegregated America's Military." Rawn James, thank you for joining us.

RAWN JAMES JR.Thank you for having me, Kojo.

NNAMDIAlan Spears, what led to the riots 100 years ago?

SPEARSThere were a variety of threads that fed into the riots. Maybe one of the biggest ones was the rapid demobilization of American Armed Forces coming off of World War I. None of the American military leadership or the politicians thought that there was going to be an Armistice in November of 1918. In fact leaders were preparing for a final offense in the spring and summer of 1919 to crush the German forces. So you have the rapid mobilization of forces and then demobilization of forces.

SPEARSAnd when these men come back to the United States their communities are not prepared to receive them. There's housing shortages, shortages of jobs. So the military hits on the idea that they'll keep these men on the payroll. They'll keep them in uniform, but they've got very few duties to discharge. So they are based in barracks and camps around Washington, D.C. They wander into the city and loiter around with a lot of time on their hands and not much to do. The second thread is that Washington in 1919 had about four daily newspapers.

NNAMDII was about to ask you about the media landscape in the District at the time and the role that newspapers played leading up to the riots and then once violence was unfolding on the streets.

SPEARSAbsolutely they were a major catalyst to the disturbance. So you had the Washington Herald, the Evening Star, the Washington Times, and the Washington Post. We're going to get back to the Washington Post momentarily.

NNAMDIWhich at the time was the smallest of those newspapers, right?

SPEARSWell, and probably one of the worst run at that point in time, which is something that the Post and their own historians have admitted after the fact. But they were competing for market share and readers. And one of the things that happened in that competition is how do you sell newspapers? Well, you have salacious headlines that get people to pick up your newspapers. And so there were lots of stories about dispossessed heiresses, lovelorn movie stars, but also about crime, and in particular African American crime.

SPEARSAnd news coming in from the spring and the summer in June and July in particular about a serial African American rapist who was targeting white women in the area. And that last thread, which is also important and involves the Post is in 1919 Raymond Pullman, the Chief of the Metropolitan Police Department, received encouraged from President Woodrow Wilson to begin really fully enforcing the anti-liquor laws, Prohibition in the District of Columbia. And that ran him a fowl of Ned McLean, who was at that point in time the publisher of the Washington Post and a substantial imbiber of alcohol. He had several well stocked liquor cabinets hidden throughout the District of Columbia.

SPEARSAnd when the MPD begin to enforce the liquor laws in 1919, he began to use the Post as a way to cudgel the reputation of the Metropolitan Police Department including by running stories about black crime, a serial black rapist. All to prove the point that the Metropolitan Police Department was incompetently run and that the officers were not up to the task of keeping people safe.

NNAMDIBut there was one headline in particular by the Washington Post that is seen by many historians as directly causing the violence to escalate. Can you tell us about that headline?

SPEARSI think what you're talking about is the --

NNAMDIMobilization.

SPEARSThe mobilization headline that broke on Monday the 21st of July.

NNAMDIThe headline was mobilization for tonight.

SPEARSMobilization for tonight. The context in that, Kojo, is that there had been disturbances on Saturday night and Sunday night. And Washington, D.C., the leaders and the African American community, the white leadership, the military, the police force, spent most of Sunday and most of Monday morning running around holding a series of meetings trying to put the riot genie back in the bottle. And they had succeeded. People were going to stay home. The soldiers, sailors, and marines, who had been involved in the first two nights rioting, their passes had been revoked. They were confined to barracks. The military was patrolling the streets.

SPEARSIt seemed like maybe by Monday July 21st everything would be back to normal in Washington, D.C., until the Washington Post published that mobilization headline, which essentially said that, tonight there will be a mobilization of white men essentially that will make the events of the last two night pale by comparison." So basically as everybody else in the city was trying to calm things down and end the riot, the Washington Post named the place and the time for a white mob to gather to go wipe out the African American communities in Washington, D.C.

NNAMDIAnd if fact there was no such planned mobilization, was there?

SPEARSThere was no such plan mobilization. And one of the interesting things about the way that newspapers ran in that day is that you could run an article or an opt-ed with no byline. So there wasn't anyone -- you can't say that it was Alan who wrote it or Kojo who wrote it and then blame us after the fact. It was just the Washington Post. And in that regard it is the responsibility of the editor, the paper in this case, Edward Beale "Ned" McLean, who allowed this to happen.

NNAMDIRawn James, as Alan has already mentioned there were many soldiers. And he explained how they happened to be in the city at that time. So tell us about the tensions that were brewing amongst the service men and between white soldiers returning from war and black civilians. What role did that play in the events that led to the riots?

JR.Well, the African American veterans, who were returning to war expected that they would be treated as veterans. They understood the city was segregated and as was much of the country at the time. And the tension brewed in that they were allowed as Alan mentioned earlier, they were allowed to wear their uniforms for three months after returning home. But the sight of an African American man in uniform incited both white veterans and white civilians.

NNAMDIWhich absolutely amazed me, because these were men who had been returning from fighting for their country and yet the right residents of Washington were incensed simply to see them wearing their uniforms on the street.

JR.Absolutely it was enough for an individual to be attacked for wearing his uniform not just arriving at Union Station, but arriving at train depots throughout the south. And this was actively encouraged on the record by members of Congress who said they believe many of these soldiers had been quote ruined by French women and we have to let them know that they are under surveillance.

NNAMDIWow. That's an amazing story. Alan, the violence began on the evening of July 19th when a white mob attacked a black couple out for a walk near 9th and D Street southwest and then a black man, who was walking home with groceries, but it escalated quickly on the second night. How did the police respond to the violence?

SPEARSOn the first night, Kojo, the Metropolitan Police Department showed up in southwest D.C. where white service members had been beating up and random blacks, just anybody that they could catch. And they promptly arrested eight or nine African Americans in that community. But the second night the police were -- they were more, I think, understanding of the fact that they were facing a real true disturbance. They began to police the situation in a way that was largely positive trying to disperse the crowds, trying to keep people safe. Although what happened in the Washington, D.C. riot to make it such a signal event it was the active participation in their own defense of the African American community here in Washington, D.C. And that helped to keep the riot on a smaller scale. It actually helped to lessen the loss of life.

NNAMDIHow did the African American community respond?

SPEARSThey responded in a variety of ways. So first there were just battles on the street with people in fisticuffs and fighting. But there were also unusual circumstances where on Pennsylvania Avenue on Sunday evening there were some African Americans, who piled into a very expensive touring car and went up and down Pennsylvania Avenue shooting at any white person in army uniform or military uniform.

SPEARSThis was not expected. If you've ever seen the episode of "In the Heat of the Night" where Sidney Poitier's character, Virgil Tibbs is questioning the older gentleman. Rod Steiger is there. And he says something the older gentleman doesn't like and he slaps him. And Sidney Poitier slaps him right back. And he has this look of -- you know, "I don't know what to do with this. I hadn't expected that to happen." And so one of the things that happened in the race riot is that white people in Washington, D.C., who were inclined towards mob activities were actually taken aback by the fact that black people wanted to defend themselves.

SPEARSOne of the things about this is the precursor to all this is the riot that took place on east St. Louis on July 1st and 2nd 1917 where -- with all due respect to African Americans, who were there and any of their descendants listening to this program. There was not an organized African American defense. And so one by one white mobs were able to go from one community to another community and they set areas on fire. Burned out at least two African American neighborhoods and are thought to have killed perhaps as many as 100 African Americans in what essentially a pogrom. It wasn't a race riot. It was a pogrom. And the course that you heard emanating from African Americans in July of 1919 was no more east St. Louis, never again.

NNAMDIThat's not going to happen here in Washington, D.C. But 39 people died. More than 100 were injured. Can you describe what unfolded over those five days?

SPEARSIt is -- well, it was a scene of intense chaos. But it's also interesting, because Washington, D.C. -- and I'm a hometown kid. This is my hometown. Has always been kind of a practical and slow moving place. And so we had a practical and slow moving race riot to some extent. You have to understand that a lot of the violence was taking place late in the afternoons or in the evenings. And, you know, Sunday people were looking forward to going to work or whatever they had to do when the week started, so not everybody in Washington, D.C. was involved in this affair.

SPEARSBut the handful of people that were you had a number of white servicemen who formed squads and they went around Washington, D.C. and they were looking for any black person singly or in groups that they could attack and beat. The soldiers had a tendency to wrap rocks or bricks in bandanas and then sling them at people's heads. That was a very effective way of knocking someone down, knocking someone unconscious. And there we battles all along Pennsylvania Avenue, Pennsylvania and 7th, Pennsylvania and 9th and then over by the White House, where a young African American man was beaten by a white mob so severely and it was within baseball throwing distance of the gates of the White House.

SPEARSSo there were intermittent skirmishes all throughout the city. The Metropolitan Police Department began responding to these. The military by Monday had canceled all leaves and had soldiers return or confined to barracks. And they also played a role in helping to disrupt the mobs. So we do have to give some credit to the Metropolitan Police Department and the military. But also to African Americans, who hung out the second floor windows in their houses that you could still see up on 7th Avenue and 9th Avenue heading towards Howard University. They fired pistols. They fired guns, rifles at the mobs, who were trying to move north and burn down Shaw.

NNAMDIWhat were race relations like between black and white residents in the District in the months leading up to the riots?

SPEARSWell, you had pointed out already that there were stories of a serial rapist -- African American rapist. And the newspapers again trying to compete for readership had really capitalized on that idea. And so you had a situation where in the District at that point in time probably about 75 percent of the people were white, about 24 percent of the population was African American. The two didn't really mix. Having interracial relationships or friendships was not something that happened on a common basis. And so when these stories about a serial rapist came out there were white people mostly didn't have any black people that they could turn to say, "Is this true? What's going on?"

SPEARSThey just simply began to believe what the newspapers were printing. And there was mass hysteria especially in June. You've got a story in a white woman in Tacoma. She's in her house by her kitchen window. She hears some rustling in the bushes outside. She screams. Her white neighbors come. They investigate the situation and determine it was just the wind rustling the leaves. But the Washington Post reports that as another attack on a white woman. And you've got to read all the way down and then turn the page to find out that in fact there was nobody there.

NNAMDIFascinating stories. We're talking with Alan Spears. He is the Cultural Resources Director at the National Park Conservation Association. And Rawn James Jr. is an Attorney and Author of "The Double V: How Wars, Protest, and Harry Truman Desegregated America's Military." Before we go to break, Rawn James, you have said that the riots here in D.C. were part of what became known as Red Summer. Tell us about the events of Red Summer.

JR.Yes. The Red Summer of 1919, so the race riots or actually small race war that took place in Washington, D.C. was part of something that unfortunately took place nationwide. It took place in Chicago as well as other cities, and, as Alan mentioned, that Americans were surprised. Both white and black Americans were surprised that African Americans fought back. And if you look back to the east St. Louis -- the terrible events that happened there that was before the war and before black men had served in the military. And when these soldiers came back many of them had -- tens of thousands of them had been trained in arms. More importantly they fully believed that they had earned the right to be treated as American citizens.

JR.And another point is that many of these African American soldiers attended training camps in the Deep South. So you had African Americans from Chicago, New York City, even Washington, D.C. -- which was segregated, but it was not Georgia -- were sent to the Deep South for these training camps. And when they came back after the war and were being attacked by white men they had seen how bad it could get having trained in the Deep South and there was a strong impetus of thinking that's not going to happen here.

NNAMDISo that in fact fueled the movement for desegregation?

JR.The movement for desegregation began with the Second World War, but what we call the Civil Rights Movement began with the effort to desegregate American's military. Military service had changed African Americans after World War I. And in going into World War II African Americans decided that they would change military service.

NNAMDIGot to take a short break. When we come back we'll continue this conversation. I'm Kojo Nnamdi.

NNAMDIWelcome back. We're about the race riots that occurred here in Washington, D.C. 100 years ago in the month of July in 1919. We're talking with Rawn James Jr. He is an Attorney and Author of "The Double V: How Wars, Protest, and Harry Truman Desegregated America's Military." Also joining us in studio is Alan Spears. He is the Cultural Resources Director at the National Parks Conservation Association. Alan, another factor at play here apparently was the early days of prohibition. D.C. had already gone dry by the summer of 1919. You mentioned that. Preceding the rest of the country in prohibition. What role did that and the fact that alcohol could still be found in the southwest neighborhood called Bloodfield, how did that play in the tensions that were building up?

SPEARSYeah. There was a tendency to refer to bootleg liquor as looking for shorty. In other words people would have small bottles of liquor that they would carry and sell to people, who were willing to try to buy bootleg liquor. Again, we go back to Ned McLean, who was the editor of the Washington Post after his father passed away in 1916. He loved liquor. He had a couple of well-stocked liquor cabinets. And it was rumored even that he had his right arm placed in a sling to steady his drinking hand. And so when the Metropolitan Police Department begins to enforce the liquor laws, the Washington Post begins to use the paper and editorials and stories to cudgel their reputation.

SPEARSAnd the idea become this. If the Metropolitan Police Department would pay less attention to enforcing prohibition laws they could catch all these criminals. They could stop the rapist from raping. And so it becomes about efficiency and it becomes a way for the Washington Post, all papers were commenting on some of this stuff, but the Washington Post was really leading the way. When prohibition began was a way to one talk about black crime, because a lot of the people, who were running bootleg liquor were African Americans, but also to talk about the ineffectiveness of the Metropolitan Police Department.

SPEARSThere was a story that I love about the Metropolitan Police Department had set up kind of a bootleg liquor check point at the D.C. Maryland line. And one officer went to hop on the sideboard of one of the cars to look in to see if there was any bootleg liquor in there. And the driver turned around and sped off and carried him into Maryland for 20, 30, 40 miles. And the story was is that finally when the car slowed down the officer hopped off and walked back to Washington, D.C. And when he was questioned, "Why didn't you arrest the people? Why didn't you pull your revolver? Why didn't you shoot?" He is claimed to have said that, "I didn't think I had jurisdiction in Maryland."

SPEARSSo the stories like that were being reported often in the Washington Post to make the Metropolitan Police Department officers seem incompetent and to question the ability of their leaders to effectively enforce the laws and keep citizens safe.

NNAMDIDidn't think he had jurisdiction in Maryland. Either that or he was having a drink with the gentleman in the car. You never know. Here is Shaka in Washington, D.C. Shaka, you're on the air. Go ahead, please.

SHAKAHey, Kojo, how are you doing?

NNAMDIDoing well.

SHAKAI was listening to one of the gentlemen. He said something earlier about the difference between the way blacks reacted in St. Louis and the way they reacted in Washington, D.C. And right away it brought to mind the difference and the philosophies between Dr. King with the non-violence and Malcolm X saying, "Well, if you bring violence then, yeah, we'll bring it back to you because then we'll be speaking the same language." I wonder if your presenter made that connection or -- that's one thing. The second thing is --

NNAMDIWell, this may have been a precursor to that debate, but go ahead.

SHAKARight. The second thing is, you know, we've got all of these military veterans today. I'm talking about today, right? And we've got the black community around the country all the siege unarmed people being shot down by the police and why are these veterans, who would -- random violence on somebody else in another country not defend their communities here from police violence?

NNAMDIThat's really complicated. But in terms of the first point that Shaka made about the responses in east St. Louis versus the responses in Washington, D.C., care to comment?

JR.Yes. Shaka makes a point that actually is made by a Christian Bishop here in Washington before -- as African American soldiers were being deployed. And the African American Bishop actually spoke to the fears of the segregationist congressmen and senators at the time. The Bishop said that, our men will go and fight for democracy abroad and then they will come home and they will fight for democracy here in Tennessee and in Georgia and we will defeat Jim Crow.

NNAMDISo there you go. All of this violence was taking place basically Alan Spears in the White House's backyard. Woodrow Wilson was president. How did he respond?

SPEARSHe didn't necessarily respond. I think it would be fair to say that President Wilson had his eyes set elsewhere. We had just concluded the First World War. We were concluding the peace for the First World War in the Armistice. Wilson would begin to really stump for the League for Nations. And I think he felt that World War I was the portal through, which the United States would go through to emerge as a world power. And so having a race riot on the steps of the White House was an embarrassment and it was something that I don't think he wanted people to pay much attention to. There is no smoking gun. No memo from the White House or from Woodrow Wilson or from anyone indicating that people shouldn't talk about the race riot in Washington or investigate it. And certainly a week later the events in Washington, D.C. are eclipsed by the events in Chicago a much larger race riot with larger loss of life.

SPEARSAnd then in September and October by the events in Elaine, Arkansas, which was another racial pogrom. But basically I think what happened is it was easy for folks in Washington, D.C. to just let the event go. And you would find that until we had people like Rawn writing on stuff like this that even some very senior historians -- African American historians, if you look for their descriptions of Red Summer, you would not find Washington, D.C. listed there. And that's because the events were surpassed and eclipsed and it faded from public memory very quickly. And I think part of that is due to the desire of the president at that time to focus on international issues and not domestic issues.

NNAMDIThe Washington Post reported in 1999 that finally President Wilson mobilized about 2,000 troops to stop the rioting, cavalry from Fort Myer, Marines from Quantico, Army troops from Camp Meade, sailors from ships in the Potomac. City officials and businessmen closed the saloons. Movie houses and billiard rooms in the neighborhoods where the violence erupted, but ultimately it was not federal troops or the D.C. police that put an end to the riots? What finally restored calm to the city?

SPEARSWell, it was a little bit of both. Again, you had the resistance of the African Americans that are taking people by surprise. They're organizing. They're setting up barricades along 7th and 9th Streets to keep mobs from going north towards Howard University and Shaw and attacking those neighborhoods. But you do have to give the Metropolitan Police Department credit. You do have to give the military forces credit. What they did by heavy presence especially on Monday July 21st and Tuesday July 22nd was to send the sense that if you were going to get together with 300 of your best friends to try to attack black people and to attack the portions of the black community that you were going to be dispersed by the authorities.

SPEARSNow what happened is you had some very intense trouble makers. Maybe now instead of 300 people there were 50 people. They would move on to a side street. And still try to continue north and find people to beat up or places to attack. But the military and the law enforcement did do a good job of helping to disperse those crowds. But what ended it -- you had mentioned the rainstorm on Tuesday, which came through and got everybody indoors.

SPEARSBut it was also the work of civilians. The civilian leadership, organizations like the Parents League, an African American organization in Washington, D.C. in 1918 and 1919 that had been working on school reform issues related to African Americans. And they were meeting with legislators and officials. And also advising people and communities, just stay home, don't go out at night, don't get involved in this stuff, stay away."

NNAMDIThis question for both of you. Most people know about the 1968 riots here in Washington, D.C. Why are the 1919 riots not well documented and not as well known? First you, Rawn James.

JR.It's a very good question. I've given some good amount of thought to. I think there are a couple of things. First that the 1968 riots now are often referred to as by some people as an uprising. It was in direct response to the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King. Whereas the 1919 race riot or small race war in the Red Summer did not have a distinct cause where one could point and say, this happened, this person was killed and immediately the city was set on fire. Secondly, because I think part of it is the fact that African Americans did shot back from atop the Howard Theater. It's less of a clean story frankly, and so that's why. And lastly I think a lot of us could do better in learning more about a lot of events related to World War I.

NNAMDIAlan Spears, same question.

SPEARSI think it also speaks to the non-linear fashion of American history, because you have -- after east St. Louis in 1917, you have this very robust defense of the African American community in the face of overwhelming odds at least on those first two nights. But then again you get Chicago and then you get Elaine, Arkansas. And then in 1921 you get Tulsa, Oklahoma, another pogrom against the African American community. And so it's hard to sort of stitch together a story that talks about things being bad and then getting better and that they're being some sort of a conclusion or a turning point in 1919. It's not that clean as Rawn said.

NNAMDIAnd then trying to track down the NAACP documents of the time, trying to track down some of the other writings of the time, apparently has been very difficult.

SPEARSSome of the documents are missing or at least I wasn't able to find them in the course of my research. The NAACP and James Weldon Johnson were in Washington, D.C. as early July 22nd. And these men were taking affidavits from witnesses, who had been a part of either the fighting or victims of the violence. They were visiting with the editors of newspapers like the Washington Times and the Washington Post, and pointing a very heavy finger at those editors and saying, you people caused this. So there is a lot of historical evidence, fact finding documents other things like that that are no longer with us or no longer available to the public that makes it a little bit harder to fill in the story.

NNAMDIAlan Spears is the Cultural Resources Director at the National Parks Conservation Association. Thank you for joining us.

SPEARSThank you, Kojo. It's been a pleasure.

NNAMDIRawn James Jr. is an Attorney. He is the Author of "The Double V: How Wars, Protest, and Harry Truman Desegregated America's Military." Rawn James, thank you for joining us.

JR.Thank you, Kojo.

NNAMDIGot to take a short break. When we come back a new program teaching entrepreneurship at Georgetown University seeks to provide former inmates with better employment opportunities. I'm Kojo Nnamdi.

On this last episode, we look back on 23 years of joyous, difficult and always informative conversation.

Kojo talks with author Briana Thomas about her book “Black Broadway In Washington D.C.,” and the District’s rich Black history.

Poet, essayist and editor Kevin Young is the second director of the Smithsonian's National Museum of African American History and Culture. He joins Kojo to talk about his vision for the museum and how it can help us make sense of this moment in history.

Ms. Woodruff joins us to talk about her successful career in broadcasting, how the field of journalism has changed over the decades and why she chose to make D.C. home.