Saying Goodbye To The Kojo Nnamdi Show

On this last episode, we look back on 23 years of joyous, difficult and always informative conversation.

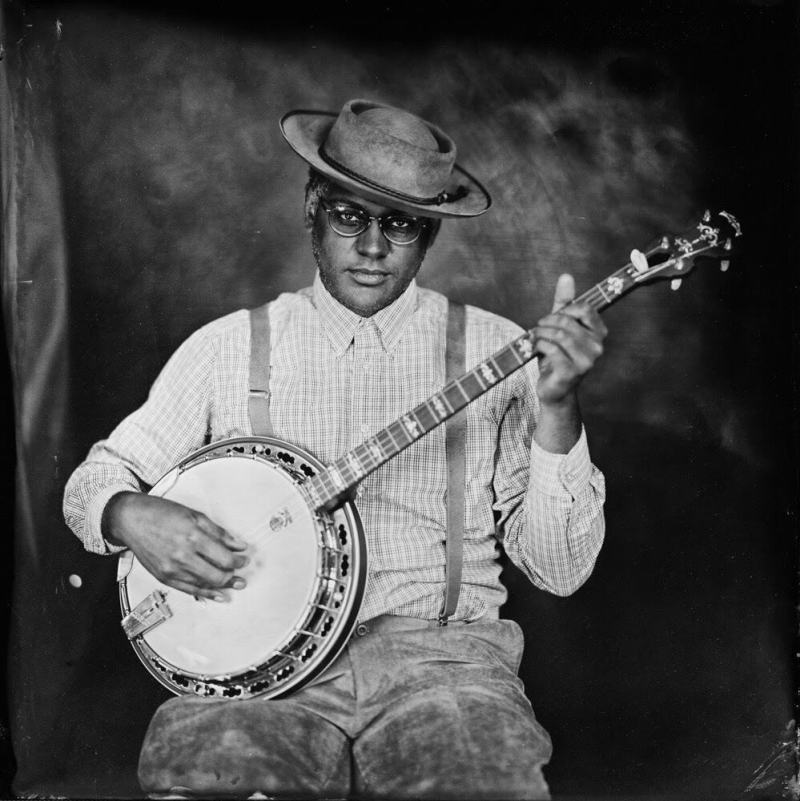

Dom Flemons

Popular depictions of the “wild, wild West” in the 19th century usually include images of tumbleweeds, horses, gun fights, and white cowboys depicted by actors like Gary Cooper or John Wayne. That picture, though, isn’t complete. Many historians believe that up to a quarter of cowboys were African-American, and many were formerly enslaved or the descendents of enslaved people.

One person pushing to re-write the historical record is Dom Flemons. He is a Grammy Award-winning music scholar, historian and multi-instrumentalist. His latest album — “Dom Flemons Presents Black Cowboys” — was released in 2018. He joins us to discuss that project, an upcoming concert, and the ongoing legacy of black country traditions.

Produced by Mark Gunnery

KOJO NNAMDIYou're tuned in to The Kojo Nnamdi Show on WAMU 88.5. Welcome. Later in the broadcast we'll discuss some programs for local youth refugees including soccer and photography camps. But first for many the images of the Wild West includes tumbleweeds, horses, gunfights, and John Wayne, but that picture isn't quite complete. The U.S. frontier of the 19th century was considerably blacker than old westerns would have you believe. Today we're exploring the contributions African Americans made to cowboy and cowgirl culture from cattle wrangling in the days after the Civil War to the country trap crossover song currently toping music charts.

NNAMDIJoining us to talk about this is Dom Flemons. Dom Flemons is a Grammy-award winning music scholar, historian, and multi-instrumentalist. Last year he released the album "Dom Flemons Presents Black Cowboys." Dom Flemons, good to see you. Welcome.

DOM FLEMONSIt's always such a pleasure to be here, Kojo. Thank you so much for having me.

NNAMDIThank you so much for joining us today. Last year you released the album that I mentioned earlier "Black Cowboys," which was nominated for a Grammy this year. Why did you choose the name "Black Cowboys" and what inspired you to delve into this back catalogue?

FLEMONSWell, the journey started about 10 years ago when I was going back home to visit Phoenix, Arizona where I'm originally from. And many years I've lived in North Carolina and as the project started to come together, I decided to move up to the Washington D.C. area to be near the Smithsonian. But going back that 10 years I was somewhere between the Painted Desert on the border of New Mexico and Arizona. And I found a book called "The Negro Cowboys," which was published in the mid-1960s and it mentioned that one in four cowboys, who helped settle the west were African American cowboys.

FLEMONSSo that stuck with me because my father, who was African American, he always loved country western music as well as movies. And we shared that love of all that ephemera, but there weren't a lot of black cowboys in that. So once I learned about the history, I just started casually first delving into it, and then eventually made this project.

NNAMDIYour father was African American. Your mother Mexican American.

FLEMONSThat's correct.

NNAMDIAnd you moved to Washington to be close to the Smithsonian and then you discovered you had moved to a town with a whole lot of neighborhoods that people Don't know about. Didn't you?

FLEMONSAbsolutely. It's been quite eye-opening to see how many different types of people and different communities flow within the MVD area. It's pretty astounding.

NNAMDIThe word cowboy conjures up images of lassos, wide brim hats, leather chaps, but many people do not know what the cowboys of the 19th century actually did. What in your view makes a cowboy a cowboy?

FLEMONSWell, a cowboy is someone, who works on the ranch primarily working with cows and serving the functions of -- each part of a ranch has a bunch of different jobs. So a cowboy usually covers a lot of different ground where first they're herding the cattle and then in the original days of the cattle drives they would bring all this cattle from say Mexico up to Texas and they would take it all the way to Abilene, Kansas and then put them on the train. And then send them over to New York City. So this was quite a lot of very hard and many times dirty work to get these cows moving, but that's kind of the image that always stuck in my mind.

NNAMDIThe dominant images of cowboys are usually white men, think John Wayne, Gary Cooper, and the Marlboro man. Yet historians estimate that as you mentioned one in four cowboys were African American. How did African Americans get into the cattle wrangling in the 19th century?

FLEMONSThey start following the work, you know. After slavery and emancipation came in also reconstruction is happening at the same time. So the development of the West is developing right alongside of the reconstruction era. So many African American people decided to go outside of state lines and put out a land claim and try to build a brand new life for themselves. And a big variety of people different economic classes different occupations, it's quite astounding when you start looking at the big picture overall -- the overarching picture. It's just the idea of black pioneers of the West as a whole. Then the cowboys symbolize this bigger movement that was going on.

NNAMDIYou know, the country that I was born in Guyana, South America a lot of it is considered tropical rainforest, but a huge swath of the country is savannas and prairies. And when I was growing up I used to go there and see cowboys at work in those areas. And many of those were black cowboys, so all over the world. Tell us about your show at the end of the month at Hill Center. What can people expect to hear?

FLEMONSWell, in my shows I usually do an overview of American roots music and, of course, the "Black Cowboys" is a big feature of that since that's my background. And also I bring in some of the songs that I've picked up in my journeys going out to North Carolina learning about early African American string band music as well as Carolina Piedmont Blues, which is a special type of fingerpicking. I also bring in some of the early songsters, which were a type of musician that usually are considered on the fringes of blues music. But they're these performers, who recorded, that they showcase a broader black folk music than we generally tend to hear and see, you know. So I tend to swap between a lot of those different things throughout the show.

NNAMDIOne of the songs you perform "Going Down the Road Feeling Bad" was recorded by many artists including Woody Guthrie and The Grateful Dead. But it was also recorded by a pivotal black guitar player and singer who lived here in Washington D.C. Who was Elizabeth Cotten and what kind of impact did she have on folk music?

FLEMONSWell, Elizabeth Cotten is a woman, who came from Carrboro, North Carolina. And that's where I lived in North Carolina. I was in Carrboro in Chapel Hill. And she was a woman that grew up in the string band tradition learning first the banjo from her older brother. And she has a story where as a young girl she was learning to play and broke the string. And her brother never scolded her, but always encouraged her to play. Later she traded in for a guitar. And as she got married and became a church member she kind of went away from the guitar for a bit until she moved up to the Washington D.C. area.

FLEMONSAnd she helped a young girl in a grocery store find her mother and the young girl's name was Peggy Seeger and her mother was Ruth Crawford Seeger. And so Elizabeth Cotton, because she was so kind and generous, Ruth Crawford hired her on as the domestic for the Seegers. And so she worked with them for a couple of years. And then one day Peggy found Elizabeth playing one of the guitars they had.

FLEMONSAnd she was an amazing guitar player. And so they encouraged her to relearn the old song she knew from way back. Peggy's brother, Mike, recorded Elizabeth and put out an album through Folkways Recordings, Elizabeth Cotten, "Freight Train and other North Carolina Piedmont songs" and it became an international phenomenon. Over a 50 year period her song "Freight Train," for example, became -- it's like the pivotal song. It's like the first box sonata you learn as a pianist, but for Carolina piedmont fingerpicking guitar playing.

FLEMONSSo Elizabeth Cotten, she played at the Newport Folk Festival and was a great hit on the festival circuit. One of the things I've been doing recently is doing a small medley of Carolina piedmont numbers here that includes "Freight Train." So I'll start off with "Freight Train" and then I'll do a little bit of "Railroad Bill" from Etta Barker, who is another wonderful piedmont picker.

FLEMONSAnd then another one from Lesley Riddle who was from Burnsville, North Carolina, and he was good friends with Brownie McGhee, but he was also really good friends with Alvin Pleasant Carter, AP Carter. And he traveled with him collecting songs for AP's group, The Carter Family. And so he's kind of another pioneer of country music even though he has not been truly acknowledged until recently. But here's a little bit of those numbers here.

NNAMDIThat's Dom Flemons, the Grammy-award winning music scholar, historian and multi-instrumentalist. He's performing on Sunday June 30th at the Hill Center in D.C. Got to take a brief break, but Don't go away. When we come back we'll hear more from Dom Flemons and hear his thoughts on the surprise trap country crossover hit "Old Town Road."

NNAMDIWelcome back. We're talking with Dom Flemons. He's a Grammy-award winning music scholar, historian, and multi-instrumentalist. His latest record is called "Dom Flemons Presents Black Cowboys" and is out now from Smithsonian Folkways Recordings. You can see Dom Flemons on Sunday June 30th at the Hill Center in D.C. "Old Town Road" by Lil Nas X, which is a fusion of trap and country music styles has been at the top of the billboard hot 100 and hot R&B and Hip Hop charts for 10 weeks. It was at the top of the country chart too until it was removed. Why was it removed?

FLEMONSWell, I think that one of the things that's really interesting about "Old Town Road" is that it has opened up a big conversation with the definitions of genres and especially in country music. Just like with different types of blues and whatnot. There are definitions that they've set in place to dictate the genre. And this song happens to have coincided with enough different elements, because it's going through an app where everybody makes memes and all these things. And it's created such a ground swell with that that I think at first there was a clerical error where they thought, "Oh, this isn't really a country song" and took it off. But the audience got so -- I mean, it was such an overwhelming backlash to this decision that the audiences demanded, you know, this is country enough for at least for what we're hearing on our side.

FLEMONSAnd so it's become this very interesting song symbolically as well as being a song about black cowboys, which I've been very deep in the subject. So to see a manifestation in popular culture less than a year after I've put out my own record that was meant to be a comprehensive overview, I think it's the most exciting thing I've seen in a long time.

NNAMDIWhat does this all say about the state of country music today?

FLEMONSI think it says -- because, again, this is coming from the audience. You know, an audience that hasn't necessarily said that they're looking for black country artists per say. And so for them to demand a black country artist like Lil Nas X. Again, there are other people as well. Kane Brown is around and Darius Rucker. There are other black country artists around. So it's not like there's nobody around. But there's a want for a paradigm shift, and I'm interested to see what happens, because to me once you realize that country music is a genre title and the black country people are a culture, those are two different conversations being had at the same with just a minute and a half song, you know.

FLEMONSSo I'm interested to see what the outcome is, because to me I've always tried to wrap D. Ford Bailey and Lesley Riddle as I played a little bit of his music in the piedmont medley. I've always tried to speak of the early African American influence on country music. Even Bill Monroe with Arnold Schultz, he was the guy who taught Merle Travis and Chet Atkins how to play the guitar. And so their style of playing is influenced by this African American performer, who didn't record. You know, because there wasn't necessarily money in records way back. But he was an influence on the community, and that influence spread out to these other people, who really innovated country music in their own way.

NNAMDIWell, I'm interested in hearing you play some more right now.

FLEMONSOf course.

NNAMDIWhat do you want to do next?

FLEMONSWell, I should do one from the "Black Cowboys" record. This is one here that features a little bit of piedmont picking. And this is one that I wrote after reading the autobiography of Nat Love, one of the famous black cowboys. This is one called "Steel Pony Blues."

NNAMDIYeah, they call him Mr. Flemons, because he's Dom Flemons, Grammy-award winning music scholar, historian, and multi-instrumentalist. Last year he released the album "Dom Flemons Presents the Black Cowboys." He is our guest. One of the 20th century's most well-known country blues singer, Leadbelly, was not from this region, but he wrote a scathing song after visiting D.C. in the 1930s. What's the story behind "Bourgeois Blues?"

FLEMONSWell, the "Bourgeois Blues" is a funny one because it matters who's telling it. See now the story that Alan Lomax and Leadbelly and their wives were traveling through D.C. And so they go into a hotel. And the Lomaxs check in because they're white. And when they show up with their friends Huddie and Martha the landlord insists that they can't stay there if there are going to be blacks.

NNAMDIYou said Huddie because Lead Belly's real name was Huddie Ledbetter.

FLEMONSAnd so it was -- the landlord insisted that they can't stay, because they Don't want any blacks there. But see based on the story you would only hear that one side of it. But the other side of it is that they then went to the black section of town and because Huddie and Martha had Alan and I believe it was his with Elizabeth with them, they couldn't get into the black hotel either. So they turned them away for having white people while the whites had turned them away for having blacks. And so Leadbelly wrote this song the "Bourgeois Blues" to talk a little bit about the hypocrisy of Washington D.C. at that time.

NNAMDIYour record "Black Cowboys" was released by Smithsonian Folkways Recordings, a label with its own rich history. What role has the Smithsonian Folkways had in documenting American folk country and blues music alive?

FLEMONSWell, the founder, Moses Asch, built the company -- actually the story goes after having met Albert Einstein. And so Moses Asch had a dream of being able to present the world's music, all the sounds of the world and be able to present them in a format that would be educational for people, because at the time LPs and Long playing Records where a new technology. And Moses Asch found there was a lot of power in being able to just put that stuff out there. Especially stuff no one wanted. And so he went out of his way to start finding -- first he went to the ethno music college conferences. And he started finding professors that had interesting field recording research that they had done in different parts of the world and started cutting them a deal to have them use their dissertations along with LP Records.

FLEMONSAnd so then, again, being a businessman he then found out a way to distribute it. And so like things like Spoken Word Records and Historical Records were inadvertently created by Moses Asch. But then over time he started recording different musical acts. Everything from at first it was Marylou Williams and Pee Wee Russell. People who had been blacklisted, but Moses Asch wanted to make sure their music was out there. So Big Bill Broonzy also recorded for him, Leadbelly as well. After Leadbelly had worked with the Lomaxs and needed another outlet outside of that particular part of academia.

FLEMONSSo Moses Asch created the space for a lot of different artists. And I believe they have, I want to say 70,000 tracks in their catalogue. They've been ahead of the game in their 70th Anniversary digitizing everything and having it available to people, because the Smithsonian basically took on the thing that Moses Asch said, which is and it all needs to stay in print always.

FLEMONSAnd so that's part of the reason I put it on "Black Cowboys." At least it will stay in print, you know. That's the one thing I can hope for. Well, I'll get one more from the "Black Cowboys."

NNAMDISure.

FLEMONSAnd this is one of a fellow who was a first deputy U.S. Marshall of the United States, who was African American, Bass Reeves. And he was said to be the historical basis for the fictional character, The Lone Ranger. And so that was something that just knocked my head off. And so I had to start searching it out and this guy is so dynamic, I write about him in the song here. But I need to take my queues from one of the great black cowboys as well the blues singer, Lightnin' Hopkins. And so here's a little bit of "He's a Lone Ranger."

NNAMDIDom Flemons, he's a Grammy-award winning music scholar, historian, and multi-instrumentalist. Last year he released the album "Dom Flemons Presents Black Cowboys." Thank you so much for spending time with us.

FLEMONSYeah, Kojo, it was such a pleasure, man. Thank you so much for having me and hopefully we get a chance to sit down and talk again sometime.

NNAMDIYou can see Dom Flemons on Sunday June 30th at the Hill Center in D.C. We've got to take a brief break. But Don't go away. When we come back we'll discuss two programs bringing sports and the arts to local youth refugees.

On this last episode, we look back on 23 years of joyous, difficult and always informative conversation.

Kojo talks with author Briana Thomas about her book “Black Broadway In Washington D.C.,” and the District’s rich Black history.

Poet, essayist and editor Kevin Young is the second director of the Smithsonian's National Museum of African American History and Culture. He joins Kojo to talk about his vision for the museum and how it can help us make sense of this moment in history.

Ms. Woodruff joins us to talk about her successful career in broadcasting, how the field of journalism has changed over the decades and why she chose to make D.C. home.