Saying Goodbye To The Kojo Nnamdi Show

On this last episode, we look back on 23 years of joyous, difficult and always informative conversation.

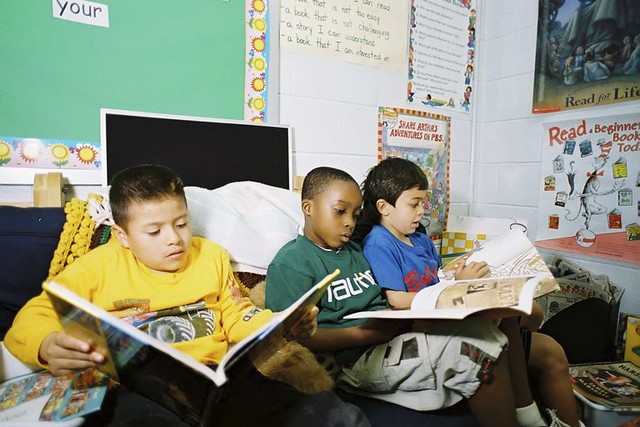

Teaching students to read is a big responsibility. So, what happens when students struggle? And what are local school districts doing to identify and support students with reading disabilities?

We’ll hear from WAMU’s Education Reporter Jenny Abamu, who’s been investigating classroom accommodations in Montgomery County.

Produced by Julie Depenbrock

Many School Districts Hesitate To Say Students Have Dyslexia. That Can Lead To Problems. | WAMU

Federal officials and researchers agree: Dyslexia is a disorder that needs to be screened for and treated. The problem is so widespread that now prisons are tasked with proactively treating dyslexia - something many schools still don't do.

KOJO NNAMDIYou're tuned in to The Kojo Nnamdi Show on WAMU 88.5. Welcome. Later in the broadcast, it's commencement speech season, we take a look at some of the best, the worst, and most memorable advice for local graduates. But first, teaching students to read is a big responsibility. So what happens when students struggle? And what are local school districts doing to identify and support students with reading disabilities like dyslexia? Joining us to discuss this is WAMU's Education Reporter, Jenny Abamu, who has been investigating classroom accommodations here in our region. Jenny, good to see you.

JENNY ABAMUHi, Kojo. Same.

NNAMDIYou've been working on this story it's my understanding for close to two months now and you focused on Montgomery County. What have you discovered in your reporting?

ABAMUSo since I've been here parents from multiple school districts have reached out for months about their struggle to get dyslexic students support in their public schools. And I specifically met one family in Montgomery County, Sarah Freedman. And while she was suing Montgomery County Public Schools after learning their fourth grade daughter was reading on a first grade reading level. She had severe dyslexia that went undiagnosed for some time. And it made me want to know why it was so hard for students to get identified and treated for dyslexia specifically in this district. And so I reported on the topic and tried to answer this question.

ABAMUI ran into some of the confusion that parents must run into all the time. Officials, who push back on the meaning of dyslexia. Sometimes they spoke about it as if it was it was a word that was made up or you could use interchangeably with other terms like struggling reader. And that was interesting to me, because dyslexia has tons of research, years of research supporting it. Their ways of supporting, screening it, identifying it, and also treating it. And I think one other thing that really blew my mind when I was researching this issue was the fact that last December President Trump signed a bipartisan crime reform bill that requires prisons to screen and treat dyslexia to reduce people coming back into the prison system. And so now prisons are required to do this while schools are not.

NNAMDIThat was the First Step Act, right?

ABAMUYes.

NNAMDIThis isn't just about Montgomery County obviously, but why did you look at that district specifically and what do you about others here in this region?

ABAMUSo Montgomery County has gone through a lot of changes in the last few years. And they're still doing a lot more things and I thought it was interesting to look at that and then also see if that got to the heart of the issue between parents and the school district. They're trying to identify and respond to reading disorders, but it's difficult especially for educators and families. And Montgomery County for me represented what a lot of school districts are experiencing and what a lot of parents are experiencing in other school districts where parents go in. They have these -- they know what dyslexia is, some of them. And they want the school district to recognize what their children are experiencing while the school district is still hesitant to do so.

NNAMDIHere is Taren in Montgomery County with a story along those lines. Taren, you're on the air. Go ahead, please.

TARENYeah. So I went to Seneca Valley High School and basically while I was there I had no idea. They didn't teach me spelling. I was struggling to read and write. I was cutting in class at least twice a week to release stress. I even was left in the classroom, because I was having an anxiety attack and the teachers left me in the classroom by myself. So there was a lot going on in that school and after, I think, four or five IP meetings now, they still want me to come back to that same school after I even attempted suicide in that school, because of all the stress that was going on. And I developed depression and anxiety from -- that stems from having dyslexia and never learning how to spell. I struggle -- have a seventh grade reading level and all this stuff that stems from having dyslexia.

NNAMDISo what are you doing now?

TARENNow I'm in the IIS program, which is from NCPS online schooling. I meet with this in-person teacher. It's a four course schooling program. So I don't have any electives. I'm barely passing it and I don't know if I'm going to pass this year. I'm a second year sophomore.

NNAMDISo are you trying to transfer?

TARENI am trying to transfer. I've been trying to transfer for two years now, last year and this year. So I haven't been going to public schools for that amount of time.

NNAMDITaren, thank you very much for sharing your story with us. Jenny, how many stories like that have you heard?

ABAMUA lot. A lot of stories like that and to be fair it's not just in Montgomery County. There are other schools districts where I hear similar stories, but, yes, it is a lot of stories like this.

NNAMDIA new law on screening children for reading disabilities passed in Maryland during the last legislative session. What does that law do exactly?

ABAMUSo the new law is a little bit tricky. It was pushed through by a group of parents known as Decoding Dyslexia. They're pushing for this all over the United States -- pushing different laws on dyslexia all over the U.S. It requires local districts to screen all kindergarten students in Maryland to recognize those, who are at-risk of reading disorders. And so the idea is they screen them in kindergarten. Then those who are at-risk, they screen again in first grade and then again later on, but it does stop short of having schools actively identify disorders and it doesn't mention dyslexia at all. Parents hope that by screening these students for being at-risk that school districts will begin to identify dyslexic students. And they say it's a good first step.

NNAMDIWell, how effective could a law like this be? What have you heard from the education experts?

ABAMUSo there are mixed opinions on how effective it will be and it really does depend on how local districts interpret the law. It doesn't -- like I said before. It doesn't force districts to acknowledge kids, who are dyslexic which is one of the big issues or -- so that's kind of one of the big problems here. And there is a risk that school districts might adopt screeners and methods for teaching or mitigating with these that are not necessarily evidence based and also don't keep up with recent research.

NNAMDIHow is dyslexia currently defined within school systems in the Washington region and why is this so fraught?

ABAMUSo dyslexia is neuro-cognitive disorder that causes an unexpectedly difficulty in reading. An individual who you would expect to have a much higher intelligence and things like that. And so it's most commonly due to a difficulty with phonological processing and it can affect lots of things about how they speak, read, spell, and even how they learn a second language.

ABAMUWhen I spoke to officials in Montgomery County, they didn't appear to have settled on what they thought it meant. The Director of Education, Philip Lynch, he kind of used the term interchangeably with the word struggling reader, which is not what scientists or other researchers would say it means. And Montgomery County, what they do now is they identify what they call characteristics of dyslexia and they try to mitigate those, which are basically like symptoms and they try to like address the symptoms of what dyslexia is.

NNAMDILet's try with David in Montgomery County. David, you're on the air. Go ahead, please.

DAVIDThanks so much for taking the time on your show to talk about what is a really important issue. I'm a parent. I have a child, who's in the second grade who's on an IEP. And what you're hearing from this report and from the student, who called in is really so consistent with what probably hundreds if not thousands of families in Montgomery County, but then obviously, you know, across the region are encountering, because once the child's on an IEP does not ensure that they're actually getting the right support and services.

NNAMDIWhat's an IEP?

DAVIDSo thank you. That's an individualized educational plan.

NNAMDIThank you.

DAVIDAnd my daughter is on one. And she's been diagnosed with dyslexia and dysgraphia. And unfortunately, despite being on this legally mandated plan that should ensure that she's getting access to services to really address her dyslexia, it's not happening. And fundamentally the reason for it is just not adequate resources specifically we don't see the right staffing levels. We don't see training for staffing. Those special education staffing or general education staffing and at the end of the day if you're not providing evidence based interventions, you're not training with staff on those interventions, and you're not providing enough staffing to meet the needs of all the children with learning disabilities and IEPs for other needs, you're never going to meet the needs of these kids, and that's really what we're -- what as families everyone's experiencing.

NNAMDIDavid, thank you very much for sharing your story with us. Joining us now by phone is Niki Hazel, Associate Superintendent of Montgomery County Public Schools. Niki Hazel, thank you for joining us.

NIKI HAZELThank you for having me.

NNAMDII know you've been listening all along. What is the county's response both to Jenny Abamu's reporting and to the couple of stories we've heard so far?

HAZELMontgomery County is taking several measures to address this issue starting with the purchase of a new curriculum that we'll be implementing over the next three schools starting in the fall. And Benchmark Advance is the name of the literacy curriculum we are implementing, and that curriculum has very specific foundational skills -- lessons that address the phonics and some of the other decoding issues that you're hearing about from your guest. And so we will ensure that as our kindergarten first and second grade students enter those first several days of school that we are doing longer dedicated lessons around foundational skills and then as we move throughout the school year and students are assessed on an ongoing basis that they will have many lessons that specifically address their needs.

HAZELSo the curriculum is one area. We also have implemented the use of primary assessments at the kindergarten, first, and second grade level specifically to address those foundational skills. So we have the DIBELS Assessment, which we've used for years, but we've really brought back and made mandatory for all of our students. DIBEL stands for dynamic indicators of basic early learning literacy skills. And really again, focused on identifying the word recognition, blending of sounds, that fluency, letter naming. And, again, we want to make sure we are catching those students, who are not making the growth that we think is adequate at each of those grade levels.

NNAMDIThis all seems very good, but I notice also in your response, there seems to be an avoidance to use the word dyslexic. Why the hesitancy?

HAZELWell, I think particularly coming from the curriculum office, our goal is to ensure that students have those skills that we are working to provide the resources necessary and the training for our teachers. Not just our special education teachers, but our general education teachers to ensure they know what to do. We have to give students time with the instruction and time with interventions before we can begin to move towards a process where we are labeling students with any type of learning disability. So we are --

NNAMDIWhat you seem to be suggesting is that at this point Montgomery County Public Schools is neither prepared nor qualified to label students as dyslexic.

HAZELWell, I can't say that. I'm only speaking from the curriculum perspective. The Special Education Office is really where you get into the assessment of students for identification. We are really talking about building our teachers capacity to identify, when there's a concern. And how we will address it with instruction. Those next steps, we call them Piers of Instruction. And so when we have a reteaching moment and that's still not working then we move into intervention. And over a period of weeks if we find that the intervention is not working still then we would move them on to having our special educators take a look at them. So from my perspective in the curriculum office, we know that we have a lot of work to do to ensure our teachers are providing that good first instruction and intervention before we move on.

ABAMUNiki, one thing that I wanted to follow-up with you on that is, I did hear from parents. They call this strategy the way to fail method, quote on quote because you have to wait for students to perform poorly before you can respond to them. And they say, "Why do this method that can take weeks or even years to have a student identified?" As opposed to proactively identifying them for dyslexia.

HAZELAnd yes, I certainly understand that frustration that has been expressed by the parents around waiting. But, again, we need to ensure that we have equipped our teachers with the right instructional strategies, because it may simply be that there's another instructional approach that's needed. And once implemented that approach that students show the progress. And so we just want to make sure that we have done everything we can before we move students into an identification process.

NNAMDIThank you very much for joining us. Our time here unfortunately is limited. Niki Hazel is Associate Superintendent of Montgomery County Public Schools. Thank you for joining us.

HAZELThank you.

NNAMDILet's move on to Prince George's County. Here's Kimberly. Kimberly, you're on the air. Go ahead, please.

KIMBERLYYes. Hi, thank you, Kojo, for having me on your show today. I just want to just be really brief. My daughter was a student within Prince George's County. And it's really nice to see Montgomery County is taking some steps. Unfortunately, Prince George's County is not taking steps. My daughter was diagnosed with dyslexia in about third grade, and we, as her parents, had to take her to an outside psychologist to get diagnosed for the dyslexia.

KIMBERLYThe school was very unsupportive in helping us even though her parents, my daughter's parents, us, we were really trying to help and work with the school. Dyslexia has been around for a long time, and I think it's a failure for the schools to not provide the assistance that they need to provide to these students, who want to learn, and it's also a disservice to the teachers who want to help the students who are struggling. Some of the teachers want to help and some do not.

KIMBERLYAnd I just want to end by saying I challenge Alsobrooks to take a look at her school system and to do something about it. And I'll even also extend a conversation. I would be more than happy to sit down with her and speak with her and also offer my help. I don't want to complain. I want to be an active parent to change Prince George's County School System, because my daughter had a horrific experience.

NNAMDIKimberly, thank you for sharing your experience with us. Angela Alsobrooks is the Prince George's County Executive. Jenny, what do we know about the process for identifying and supporting students with reading disorders in neighboring counties like Prince George's County?

ABAMUWell, the thing about knowing the process is that they vary from student to student, because a lot -- and a lot of these students who go through these identification processes usually a private experience for a lot of them. And so you'll see students like Niki, who mentions that they go an interaction process and however long that takes that varies from kid to kid. And so it's really hard to tell exactly what parents here, what parents get in response, but we do know that this is -- it seems to be like it's a very difficult thing for a lot of families. And like caller just said, and all the callers have said, even parents who are proactive who know what dyslexia is and who know what they're children have still have a hard time getting districts on board with them.

NNAMDIHow do local districts like Montgomery, Prince George's, Fairfax, and Washington D.C. rate when it comes to reading proficiency?

ABAMUSo about 50 percent of students in Montgomery County are testing proficient in reading. Now I say testing because, you know, they might be good in other places and not good at tests, so we should also just keep that in mind. When we look at testing in Washington D.C., of course, they use about the same exam, which is PARK and on that exam about one third of students are testing proficient in reading. And nationwide, about 40 percent of students test proficient in reading. So we're looking at a real issue. Reading is a big thing. It's a science. It's not easy to teach, like some of the parents noted before and it gets even harder to teach when you don't know what students need.

NNAMDIYou talk about the effects of falling behind in reading like the school to prison pipeline. What do we know about students who don't learn to read by third grade?

ABAMUSo up until third grade you're learning to read and usually after that districts are at basically reading to learn. And so if you don't learn to read you will fall behind in school in all different kinds of classes, because there's word problems in math and all things like that. So you have to be able to read at a certain point to do well in school. And the prison population is high. It has a lot of students, who have dyslexia.

ABAMUThe Marshall Project did some great reporting on this where they looked at how certain prison populations had such numbers of people who have reading disabilities and one of the greatest numbers was dyslexia. And so that study in Texas found that 50 percent of the inmates were dyslexic. And the fact that so many of these children are growing up and not being able to read and losing options and ending in poverty and, you know, it's a bad cycle. And so that's something that I think is really fascinating to think about, because if schools don't treat and identify students they might not get that until they're behind bars.

NNAMDIPBS did a story about the Arkansas School System, changes they made to their reading curriculum when school officials saw too many students falling behind. What did Arkansas do?

ABAMUSo I was fascinated by that series too, because Arkansas is making some big investments to change their reading curriculum. And they're basically doing it across the board as a state. And so they're looking at curriculum that supports dyslexic students specifically and then using that to teach all students. Of course, they'll vary it depending on students' needs, etcetera. But they're definitely taking a whole revamp approach, because if you're thinking about, for example, if the numbers are one in five like some researchers project that's a really high number of students. And so some districts have said, you know, this would be very very expensive to do on a one to one level. We need to look at our entire curriculum. Everything that we're using and revamp that and use it, make sure that we're using things that help dyslexic students. And so that's what Arkansas was doing. It's a lot of money. It's very expensive and it's a lot of work.

NNAMDIFinally, we've got a comment from MCG on our website who says, "Testing to identify reading challenges is only the first step, with properly trained teachers, dyslexic students can excel." And to add to that, here is Sarah Freedman with whom you spoke in Chevy Chase. Sarah Freedman, you're on the air. Go ahead, please.

SARAH FREEDMANYes. I was calling in. I'm Sarah Freedman. I spoke with Jenny Abamu about my daughter and her experience in Montgomery County Public School system. Having very severe dyslexia and essentially was just continually pushed through until the end of third grade when we pulled her. My question was and I know that the Assistant Superintendent is no longer on the phone, but we haven't heard anything by way of how do they plan to -- or what do they plan to do with the children, who they are screening for, you know, reading struggles and potentially dyslexia. And how are they preparing the classroom teachers?

NNAMDIOkay. We don't have any more time. I'll have to have Jenny respond to that and then we've got to take a break.

ABAMUWell, Montgomery County is doing quite a few things. They're trying to start at least. They've requested federal funds to start training some teachers in the Orton-Gillingham method, which is a method that uses -- a multisensory approach to teaching reading that's specifically designed for dyslexic students and so that is an evidence based approach. And they're trying to adopt that for some teachers. Of course, some families say, you know, a lot more teachers will need this training than what Montgomery County is currently doing, but it is a first step that they are taking.

NNAMDIA lot more people wanted to join this conversation too. It's one we'll have to continue at a later date. Jenny Abamu, thank you so much for joining us.

ABAMUThank you for having me.

NNAMDIJenny is WAMU's Education Reporter. When we come back it's commencement speech season. We'll take a look at some of the best, the worst, and most memorable advice for local graduates. I'm Kojo Nnamdi.

On this last episode, we look back on 23 years of joyous, difficult and always informative conversation.

Kojo talks with author Briana Thomas about her book “Black Broadway In Washington D.C.,” and the District’s rich Black history.

Poet, essayist and editor Kevin Young is the second director of the Smithsonian's National Museum of African American History and Culture. He joins Kojo to talk about his vision for the museum and how it can help us make sense of this moment in history.

Ms. Woodruff joins us to talk about her successful career in broadcasting, how the field of journalism has changed over the decades and why she chose to make D.C. home.