Saying Goodbye To The Kojo Nnamdi Show

On this last episode, we look back on 23 years of joyous, difficult and always informative conversation.

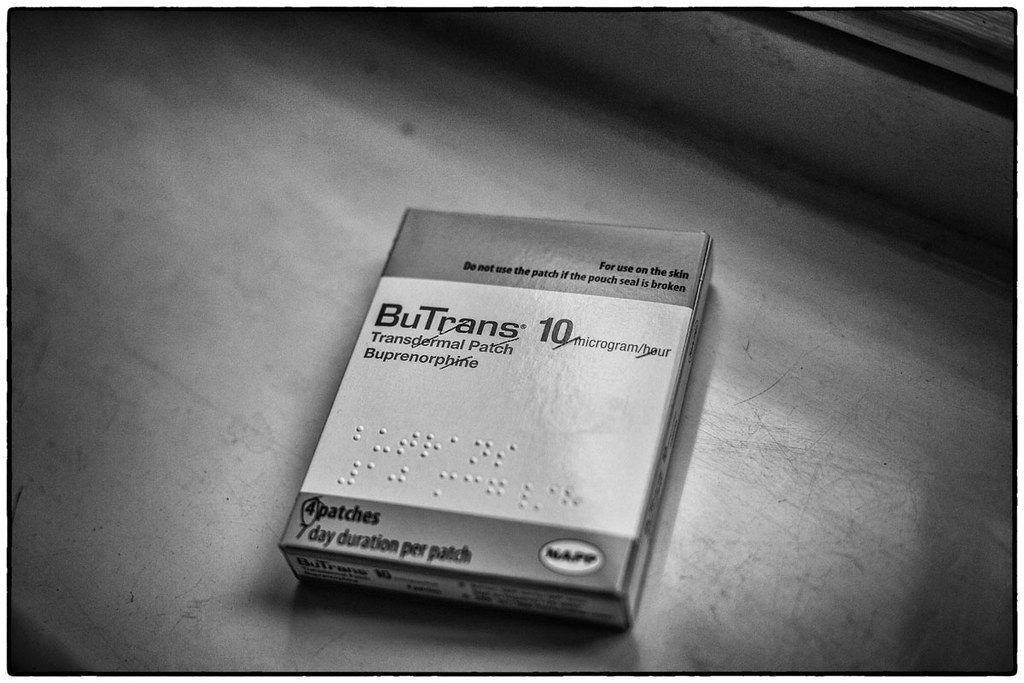

A buprenorphine patch.

Three D.C. hospitals now have programs providing medicated addiction treatment to overdose victims in emergency rooms.

D.C. saw 192 fatal opioid-related overdoses last year and up until recently, had no hospital program to transition emergency room patients to opioid addiction treatment. The District’s new program, which is running out of Howard University Hospital, MedStar Washington Hospital Center and United Medical Center, will offer the drug buprenorphine, which treats cravings for addictive opioids.

We learn more about the program, and how it fits into the District’s plan to address opioid addiction at large.

Produced by Ruth Tam

KOJO NNAMDIYou're tuned in to The Kojo Nnamdi Show on WAMU 88.5. Welcome. Later in the broadcast we'll be hearing from a collective of 10 Maryland musicians as part of our look at local bands who entered NPR Music's Tiny Desk Contest. But first, three D.C. hospitals now have a program designed to transition emergency room patients, who have overdosed from opioids to medicated addiction treatment. In recent years, the District has seen big increases in fatal opioid overdoses. Last year, over 200 were recorded. Here to help us understand the new program and where it fits in to the District's overall plans to address the opioid crisis is Peter Jamison. He is a reporter at The Washington Post. Peter, good to see you again.

PETER JAMISONHappy to join you.

NNAMDIAnd joining us by phone is Edwin Chapman. Edwin Chapman is an Internal Medicine Specialist and the Medical Director at Medical Home Development Group. Dr. Chapman, thank you for joining us. Peter, what hospitals are now offering addiction treatment and why these locations?

JAMISONSo the three hospitals that are participating in the new program are Howard University Hospital, MedStar Washington, and United Medical Center. UMC, for those of your listeners who don't know, is the public hospital owned by the District of Columbia, the only full service hospital in southeast Washington. It's also the hospital that routinely sees the highest number of overdose victims in its emergency room. So those are the three hospitals sort of spread out across the city that are involved in this program.

NNAMDIDr. Chapman, you're there?

EDWIN CHAPMANYes. I'm here. Thank you.

NNAMDIDr. Chapman, before this program, what would happen if someone wound up in the hospital after an overdose?

CHAPMANWell, they would be given Narcan generally, which would reverse the overdose and prior to that time discharge hopefully with a referral to a treatment center. So these are typically done by paper. So the patient would be given some kind of direction once they've awaken, but the problem is that most often across the country patients, who have had their overdose reversed would likely go back to the same habits that they had before. So they would feel very bad and then seek the same drug that they took initially.

NNAMDIThe program now running at Howard University Hospital, MedStar Washington, and United Medical Center is a medicated treatment program. What drug are they using and how does it work?

CHAPMANWell, the idea is to immediately give that patient buprenorphine, which is one of the three medications used for opioid treatment. The other medications are methadone and vivitrol. But under these circumstances vivitrol would not be effective and methadone would generally not be given, because of the complexity in giving it. So a first dose of buprenorphine would be the appropriate way to go.

NNAMDIWho -- Peter Jamison, first you. Who is this program for and do we know how the process of entering treatment will work?

JAMISONYeah. So the program is designed to reach out to overdose victims, who show up in the emergency room. And all these efforts are based on a study that came out of Yale University in 2015 that showed -- sort of demonstrated empirically something that doctors had long observed, which is that the immediate aftermath of an overdose is often the best time to sort of catch a chronic drug user and get them into treatment.

JAMISONSo what they started doing in 2015 at Yale New Haven Hospital and the strategy has now spread to many other hospitals across the country is they'll begin treating overdose victims with buprenorphine almost immediately after they come in. And buprenorphine is a medication that diminishes opioid cravings. Buprenorphine is itself an opioid as Dr. Chapman could explain to you. But, you know, the idea is that there's no reason to delay putting people on this medication.

JAMISONYou know, you don't need to be detoxed to begin it. So what they found is that if patients begin taking it, that's initial step into the recovery process that gives them better long term success. So what will be happening at these three hospitals is patients, who come in who've recently overdosed will -- you know, contact will be made with them by an outreach worker in the hospital. And they'll be offered the option of beginning buprenorphine treatment with the hope that this is something that they'll continue doing in the long term and continue a long term recovery process from using heroin or whatever other opioid that they were addicted to.

NNAMDIDr. Chapman, Peter Jamison's just said that buprenorphine is itself an opioid. So how does it differ from methadone and why is it not itself addictive?

CHAPMANSo buprenorphine is what we call a partial agonist. Methadone on the other hand is what we call a full agonist. So methadone does everything that heroin, morphine, and other opioids in that class would do in that they have a propensity potential to cause respiratory depression or even patients can get high if they get too much. On the other hand buprenorphine is a much safer and easier way to initiate treatment as a partial agonist. So it does not have the tendency to cause the kind of respiratory depression. And you would actually have to misuse the medication or be opioid naïve in order to obtain a high with this medication.

CHAPMANSo it is an opioid. It's what we call a replacement therapy. And it does not mean that once you start this medication that it will necessarily be easy to come off the medication. But, again, it's much safer.

NNAMDIHere's Meredith in Annapolis, Maryland. Meredith, you're on the air. Go ahead, please.

MEREDITHHi. Can you hear me?

NNAMDIYes. We can.

MEREDITHOh, this is so exciting. Okay. Yeah, my name is Meredith. I'm the buprenorphine expansion coordinator for the local health department and I live in Annapolis. So I'm really excited to hear that there are similar initiatives going on in the emergency department around D.C. But my question is what is the community capacity in D.C. for physicians, who have their waiver to continue prescribing suboxone after the initial dose is given in the ED? Because that's a big challenge, in our county, is that, you know, while we can provide -- like administer the medication, it's difficult to find follow-up care for people.

NNAMDII'm glad you raised that question because -- Peter Jamison, I'll ask you first. What happens to patients after receiving a dose of buprenorphine? What organizations are the District partnering with to continue treatment?

JAMISONSo there are various local community organizations that the District and the D.C. Hospital Association are partnering with to have people continue their treatment after they leave the hospital to address the question that was just raised about the capacity of buprenorphine that would be providers in D.C. and suboxone, which the caller mentioned is simply the brand name of buprenorphine. D.C. is in the situation that it's very different from some other parts of the country where there are acute shortages of doctors or health care providers who can prescribe buprenorphine.

JAMISONYou know, you read about people especially in rural parts of the country, you have to drive hundreds of miles for an appointment with a doctor to get their buprenorphine. That's not the case here. The city has actually been very successful in expanding the number of buprenorphine providers, the number of doctors who are licensed to provide this type of treatment to patients.

JAMISONWhat we've seen here is that there's been a gap in terms of connecting with patients, who would actually take advantage of those therapies. So the hope with this program is that, you know, the city now has this fairly large stock of doctors, who are prepared to treat patients with buprenorphine. They just need to start seeing more patients. And, you know, this will be one way to make contact with those patients and steer them towards treatment.

NNAMDIAn anonymous listener emailed, "I work on a daily basis at the one and only facility in the District of Columbia that offers medical detox for people addicted to opioids, who have Medicaid or no insurance. We are woefully underfunded. We're able to send about 30 percent of our patients to in-patient treatment. For the remainder there is absolutely no funding for community based support. We need help. We see people die all the time." In your reporting, is there something that you've found?

JAMISONYeah.

NNAMDIAbout Medicaid patients?

JAMISONWell, and this is an issue that people have raised repeatedly is that when it comes to detox, which is the period -- and, again, for buprenorphine -- and Dr. Chapman could speak to this more extensive. But you do not need to actually be detoxed before you begin taking it. And that's a key point about this medication. But for those who do choose to go through supervised detoxification, who have been addicted to drugs or alcohol in the long term, we have heard repeatedly that those facilities, you know, are not adequate to what the need is in D.C. right now.

NNAMDIGot to take a short break. When we come back, we will continue this conversation. I'm Kojo Nnamdi.

NNAMDIWelcome back. We're discussing D.C.'s opioid epidemic and measures taken to address it with Peter Jamison. He's a Reporter at The Washington Post. Dr. Edwin Chapman is Internal Medicine Specialist and the Medical Director at Medical Home Development Group. Dr. Chapman, we heard our last caller indicate that she was calling from Annapolis, Maryland. So we know that programs exist in Maryland. But where else do programs like this exist and what do we know about their effectiveness?

CHAPMANWell, these programs are now being ramped up hopefully around the country and we're very fortunate to be one of those programs. But we think that perhaps based on the last caller's comments that because of our population -- 40 percent of our population is technically homeless in that they are either homeless on the street. About 16 percent are in a shelter. And the compliment, our homeless in that they live with relatives or friends. The other problem with this population is there's a very high incident of mental health problems.

CHAPMANSo that at least half the patients suffer from anxiety and depression and the other patients have higher mental health needs. So if you could imagine giving a patient a dose of buprenorphine in the emergency room, but yet they are returning to the community with mental health problems and housing difficulties that we may have not so good an outcome.

CHAPMANSo we really need to look at that aspect of it. And I think what has been suggested as recently as Tuesday at a meeting at the Association of American Medical Colleges, we had a rather extensive symposium on this issue. And it was suggested that perhaps our patients be given some respite in that they perhaps should be admitted for several days so that we can get a handle on these mental health and housing problems. So that we don't have this revolving door phenomenon. So that was something that we might be able to uniquely implement here in Washington that could be used around the country. So these are works in progress.

NNAMDIPeter, the District has a deadline to meet when it came to this program, April 30th. There was concern from local hospitals about meeting that deadline, why?

JAMISONIt's unclear why the concern existed. These programs have been a long time coming. And, you know, Dr. Chapman was actually involved in an earlier iteration of one of these programs. It was initially planned for United Medical Center that was supposed to have gotten underway almost two years ago that was not carried out because of various bureaucratic issues at the D.C. Department of Health. But -- I'm sorry Department of Behavioral Health. But the -- you know, when we started reporting on -- these issues are part of a broad effort to address the opioid epidemic in D.C. that Mayor Bowser announced in December.

JAMISONAnd, you know, as we began reporting on how these various initiatives were going to roll out, there was some question about whether all the hospitals would be able to get these programs up and running in a timely way. Specifically Howard University Hospital had initially said that they were going to get their program started in July. After some pushback from the mayor's office, they said that, in fact, they would be able to meet the April 30th deadline. And from what we've been told all the hospitals did in fact meet the April 30th deadline.

NNAMDICan you remind us compared to other similar cities -- because we see comparisons to states, but compared to other similar cities, where did the District stand when it comes to opioid overdose deaths?

JAMISONSo the District has an extremely severe opioid epidemic, the rate of death, just to give your listeners some sense, especially when you look at the rate of death among African Americans is higher than the rate of fatal opioid overdose for whites in states like West Virginia or New Hampshire or Ohio that are much more typically associated with the opioid epidemic. And the population that's being affected is mainly older African American men, who have used heroin in some cases for 30 or 40 years with relative safety. Over the past several years as their heroin supply has become tainted with fentanyl, a synthetic opioid that's extremely potent can cause death in very very small amounts. Overdoses in D.C. have just skyrocketed.

JAMISONSo in 2017, the number of fatal overdoses in D.C. peaked at 279 deaths, four out of five of those victims were African American. The numbers leveled off somewhat in 2018, last year, went down to 213. Still a number higher than the number of homicides in the District and it's not clear exactly what's driving the decline. This is a decline that has been witnessed nationwide. You know, some people speculate users are adapting somewhat to the presence of fentanyl in heroin and be more careful in how they dose themselves.

JAMISONAnother theory is simply that there is a limited number of people in this cohort that was most affected by the opioid epidemic in D.C. You know, there's only so many long term heroin users in the city and that they may simply have begun dying out. So there a few of them to die of fatal opioid overdoses.

NNAMDIDr. Chapman, does this program put the District where it needs to be to effectively address the local opioid crisis. What does it need to do to meet its goal of having fatal opioid overdoses end next year or to have -- not end, cut in half?

CHAPMANYeah. There's several things. One is this program and we really need to look very closely at the early outcomes. The second is that we need to treat opioid addiction as a medical problem, so that we really need to merge this effort with the criminal justice system so that people are not incarcerated for treatment and then discharged back into the community. So another national problem is that most of the jails do not use the three medications that we talked about earlier. And if you're on a medication they would actually take you off of that medication in many circumstances, which is really a moral problem from our standpoint, from the medical standpoint, because you would not do that with a diabetic, who is on insulin or hypertensive who was on medication.

CHAPMANThe third issue are patients, who are chronically using opioid pain medications from a physician. What do they do when the physician can no longer fill that medication? So we have this conundrum where doctors are now really scared to continue treatment and have stopped treatment in many instances, which forces that population into the street market for medication, which of course ends up frequently being fatal.

NNAMDIWe only have about a minute left. But we got a note from an anonymous emailer who says, "Buprenorphine is only available to patients with active insurance, Medicaid included. We need funding for patients not covered with insurance." Know anything about that, Peter Jamison?

JAMISONBuprenorphine is actually -- I'm sorry. I was about to speak about naloxone. I don't know about the expense of buprenorphine when it's not covered by insurance. Dr. Chapman might know more about that.

NNAMDIDr. Chapman, you got about 30 seconds.

CHAPMANYes. You have to have insurance for all three modalities of treatment. The District does cover methadone if a patient goes to a methadone clinic, but that also can be a barrier. So the caller is absolutely right. All of these patients, once they're diagnosed should immediately be able to get insurance. So we need to have a mechanism to speed up insurance coverage.

NNAMDIEdwin Chapman is an Internal Medicine Specialist and the Medical Director at Medical Home Development Group. Dr. Chapman, thank you for joining us.

CHAPMANThank you.

NNAMDIPeter Jamison is a Reporter at The Washington Post. Peter, thank you for joining us.

JAMISONHappy to be here.

NNAMDIGoing to take a short break. When we come back, we'll hear from a collective of 10 Maryland musicians as part of our look at local bands who entered NPR Music's Tiny Desk Contest. I'm Kojo Nnamdi.

On this last episode, we look back on 23 years of joyous, difficult and always informative conversation.

Kojo talks with author Briana Thomas about her book “Black Broadway In Washington D.C.,” and the District’s rich Black history.

Poet, essayist and editor Kevin Young is the second director of the Smithsonian's National Museum of African American History and Culture. He joins Kojo to talk about his vision for the museum and how it can help us make sense of this moment in history.

Ms. Woodruff joins us to talk about her successful career in broadcasting, how the field of journalism has changed over the decades and why she chose to make D.C. home.