Saying Goodbye To The Kojo Nnamdi Show

On this last episode, we look back on 23 years of joyous, difficult and always informative conversation.

Guest Host: Marc Fisher

SONY DSC

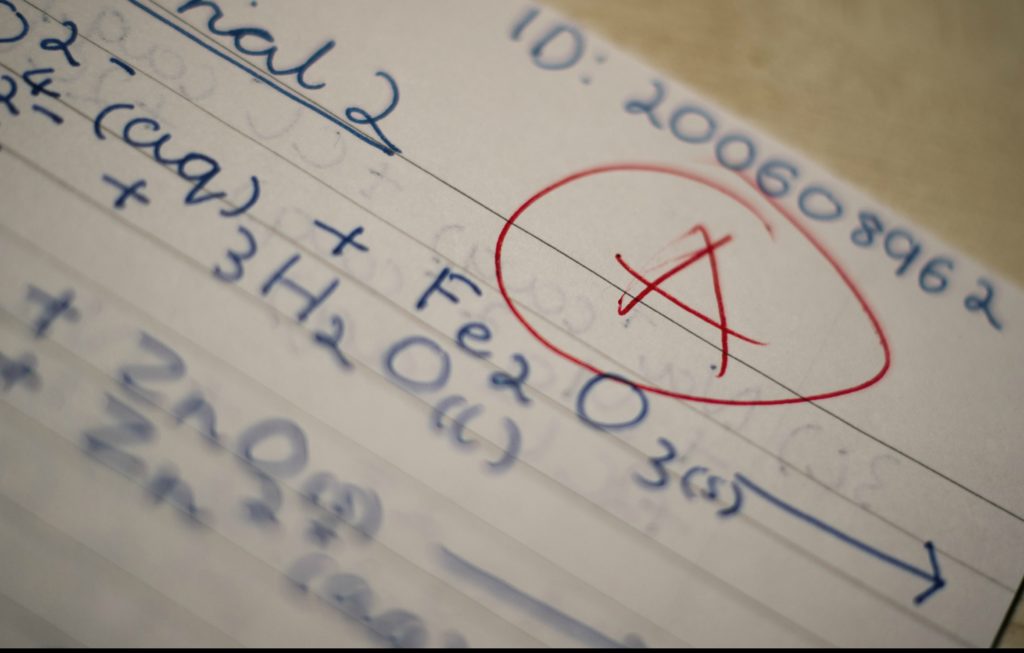

Either students are suddenly more studious, or a new grading system is making it much easier to get an “A” in Montgomery County high schools.

What’s behind this batch of glowing report cards? And what does it say about the value of a Montgomery County diploma?

Produced By Lauren Markoe

MARC FISHERWelcome back. I'm Marc Fisher, sitting in for Kojo Nnamdi. High school students are getting many more A grades and fewer low grades than they did just a few years ago in Montgomery County and elsewhere around the country. And many teachers, parents and even -- believe it or not -- some students are worried that new grading policies have made it too easy to get high marks. What are the consequences of this new grading system? Is there less incentive to work hard? Will college admissions officers notice the blizzard of A's? Joining us to discuss how students should be held accountable for what they learn are Maria Navarro, the Chief Academic Officer for the Montgomery County Public Schools. Welcome.

MARIA NAVARROHi.

FISHERAnd Patricia O'Neill is Vice President of the Montgomery County School Board. Welcome.

PATRICIA O'NEILLGood afternoon.

FISHERChristopher Lloyd is President of the Montgomery County Education Association Union that represents teachers in the county. Thanks for being here.

CHRISTOPHER LLOYD(overlapping) Thank you. Good to be with you.

FISHERSo, let's start, Christopher Lloyd, with you. Recently, the system reported that the percentage of A's in core math courses has nearly doubled in the last few years, and there were steep rises in English and social studies -- English and science courses, as well. Why is that happening?

LLOYDWell, three years ago, the District made a change to the grading policy. At that point, 70 percent of our members had said that that would result in increasing grades, and sure enough that prophecy has come true. We find the grading policy really did change how grades were computed, and we believe that plays a significant role in the increased number of A's.

FISHERAnd, Maria Navarro, what was the rationale for the change?

NAVARROWell, I would start by saying that we've been looking at this issue of grading for a while. The board has engaged. You know, we have a history starting in early 2000s to look at really what a letter grade, what grading really means and tells us about what students are learning. Specifically, more recently, we moved to take a look at what constitutes a grade. What assessments do we put together in terms of the District? How are those assessments aligned to standards the students must meet and know? And we've also expanded opportunities and options for students to take certain classes. I mean, you mentioned the math, specifically the algebra one. We've expanded the number of students that now are taking algebra classes earlier in our school system.

FISHERPatricia O'Neill, there was a piece in the Walt Whitman High School newspaper a little while ago by a student named Tiger Björnlund, who wrote that the teachers had opposed the eliminating final exams, and yet the system went ahead and changed the grading system and eliminated the countywide final exams, anyway. He was upset and worried that the new system would cause grade inflation to skyrocket, making high grades less meaningful, and expressed the worry that colleges would assume that A's are no longer an indication of intelligence and hard work. Are this student's concerns valid?

O'NEILLWell, when the system looked at the issue of final exams, it was in the context of trying to allow more time for instruction. What were the components of a grade? We eliminated the final exam, which counted 25 percent of the semester grade. So, who would the report card be monitored? We went to a system of end-of-quarter assessments or check-ins, which count 10 percent of the grade. And it forced the system to change the grades. There was extensive input from the councils of teaching and learning, from middle school, high school, from principals, from students, from parents. This decision to change wasn't done in a vacuum.

O'NEILLHow the grade then is computed is problematic, because if you earn an A the first quarter and you earn a B the second quarter, they're calculated based on an A being four points, a B being three points. It averages out to a 3.5, which is reported as an A. I would argue that we need to have a more discreet, defined grading system of percents or pluses and minuses. But we do need to look at the issue, the issue of the final exams as one component and the issue of how we calculate grades.

FISHERChristopher Lloyd, this student who wrote this piece and others have drawn this connection between the decision to eliminate the final exams and the resulting -- what they see as the resulting grade inflation. Is that a fair connection to make?

LLOYDI think it's a fair connection to make, because when you eliminated the final, you went from three grades in the semester that computed the semester grade down to two. And as Pat just said, what you end up with then is the possibility that a student could get an 89.5 first quarter, a 79.5 second quarter. That would be computed as an A and a B. There's no rational reason if you actually average those two at an 84.5, um, that that student would have an A for the semester, but that's exactly what happens. Absent the final, you have that missing third grade, and so that, in essence, is where we are.

FISHERMaria Navarro, this focus on grades obviously extremely important for students, especially those heading to college. And yet we seem to have a country where things are going in two directions, two opposite directions at the same time. In some places, we have grade inflation, in other places we have much tougher grading systems being imposed. What is the reason why we're seeing this kind of reexamination of grading at this point?

NAVARROWell, I think going back to a point that Chris just made about the final exams and sort of having three grades, the marking period exams and then the final exams, part of what we need in education to go back to is: what does a grad mean? And it's one of multiple measures of looking at what we know students know. An assessment -- a one-time assessment tells us something about what a student knows at that one point in time. The grades should constitute cumulatively, both for the student -- I would argue also for the parents -- but also for teachers, to know how students are doing.

NAVARROSo, if we base it -- I know when I went to college and, you know, we had that one test in one of the classes, and that sort of made it or broke it for you. And then they had to deal with curving issues, because it was a one-time assessment. Really, if we want grades to be a measure of what kid know, are able to do, and then as educators, how we use that data to then impact what else we need to be doing to support students, then I think it comes to question around moving away from an exam, a final exam, a one point in time solely to assessments that are first and foremost standard aligned. And second, that they're given more often. And this is one of the things that we heard from our communities, also, around given more often, so that we could actually know how students are doing and not wait until the very end.

NAVARROWe heard from students saying, you know, I will average out my grades, and if I don't have to take that final or if I don't have to study as much because I'm going to pass my course, I mean, I'd do that. Or for students who are working really hard and are going to be impacted negatively by one assessment that has, you know, such a huge impact on their grades. So, part of it is we need to go back and really put a value system.

NAVARROTo your point around what does the higher education think about it, we researched that when we were looking at this. And we talked to higher education. We talked to University of Maryland system. We talked to professors, the higher education, looking at also moving towards multiple data points that tell them, not that one or two tests in their courses. And they frankly have shorter periods of time by which they give semester exams or have a cumulative one.

NAVARROSo, we looked at multiple those points to really assess what, at the end of the day, what is a grade for us? It's a measure of looking at what students know and are able to do. And, once again, it's not a one-time thing. It is a continual view of how it's supporting student learning.

FISHERAnd, of course, colleges are struggling with this issue themselves.

NAVARROAbsolutely.

FISHERHad a number of schools that have tried to push back against grade inflation with very limited success, if any. Let's hear from John in Lorton, Virginia. John, you're on the air.

JOHNHey, good afternoon. My daughter has just completed her time getting enrolled and accepted into colleges. It's a really, really big and involved -- I won't say conspiratorial, but very complicated game between colleges and high schools. I was going to ask the commentators, we have SAT, SACT testing which provides generally even-keeled and scaled way for colleges to measure students. But the 4.0, 5.0 AP-type grading system's clearly antiquated. What is the environment of the nationwide school systems and educational brain trust toward maybe evolving to something a little more, let's say, scalable, maybe a 10-point grade system, so that the A and the B don't just average out to be the 3.5 A?

FISHERPatricia O'Neill, should there be a nationwide standard in grading? Is the haphazard system we have sufficient?

O'NEILLWell, you know, as we embarked on our grading and reporting journey here in Montgomery County, which began about the year 2000, as there was a move toward high stakes testing in various states, we know, we looked across this country at various grading systems. And I have to say, there really is no universal grading system that seems to be perfect. There are those outside measures -- there should be a direct correlation. A child who receives an A in a course should be able to do well on outside measures such as SATs, IB, advanced placement exams, whatever the state accountability system are, you know, so that there is no surprise.

O'NEILLYou know, grades are intended to communicate information about how students are doing, actually doing. Not a reward, not a punishment, but communicate information to parents, to teachers, to students. And at the end of the day, there should be no surprise. All of them should correlate to how a student is being prepared.

FISHERBut--so this brings us back to the student's point, the Whitman student who wrote a critique of the current grading system, because his argument was an A at Walt Whitman, with its very high-achieving student body, should have a meaning that's perhaps different from an A at a struggling school, where there aren't as many high achievers.

O'NEILLWell, that's why we went to a high stakes -- I mean, to a standard space grading system in Montgomery County. And we had gone to a countywide system of final exams. MCPS had final exams prior to 2000, a system, but they were locally developed. We went to countywide final exams, and we discovered, at that point in time, prior to establishing a countywide system of grades, that, you know, an A wasn't the same at Whitman and Wheaton, and that there was curving of grades. There was extra credit. So, we have been working diligently since 2000 to have a standard space grading system so that an A is the same across our 25 high schools.

O'NEILLThat is vitally important that a student, wherever they are in Montgomery County, has a great teacher, high quality instruction, held to the same standards, and that we know how they're actually achieving.

FISHERWe have a Tweet from Charity, who says: tests aren't particularly accurate either. Perhaps a monthly grade would be a better measure of students' success. And, in fact, the system seems to be moving almost in the opposite direction in that there's some critique that if you work hard for a few weeks in a course, you get a grade that really sets your grade for that semester, and you can kind of slack off after that. Is that what's actually happening in the classroom, Christopher Lloyd?

LLOYDYeah, we see that -- the teachers see that it has an impact on both effort, as it has an impact on attendance. We see that posing a major problem. At the end of the day, having the number of A's double within a three-year span either says that we have one heck of a difference in the gene pool over that time, or as teachers, we have -- we are knocking it out of the park. We just turned the switch on. We just didn't -- we didn't want to do it prior to then, neither one of which makes sense.

LLOYDAn A has to mean an A to the community. And if these grades, as they stand, are okay with the community of Montgomery County, then that's one conversation. If Montgomery County says, listen, that's odd data. It doesn't seem to make sense to me, then we should have an audit of our grades, so that we can be able to determine what's going on and what the impact of the policy was.

FISHERMaria Navarro, what some students have been worried about and what, I guess, some teachers are concerned about is this idea that you can have an A in the first quarter, a B in the second, and end up with an A for the semester. Is that correct, and is that -- well, how is that justifiable?

NAVARROWell, so that's the calculation that Ms. O'Neill was talking about, because right now, our grading system is an A, B, C, D or E...

FISHER...with no pluses or minuses.

NAVARRO...with no pluses or minuses. And so I think Ms. O'Neill calls for maybe more specifics within that A, B -- but I would like to go back to this question of yes, there have been some changes that we have made. For example, the class of 2018, we used to have in place policies that if you're a student and you take a class and you fail it and you take it again. And let's say you failed the first class, and then the second one you get a B, then the question is, we used to average those two out, the F and the B. And we moved to change the policy to say if a student actually gets a B and retakes the class, that should be the grade that moves forward in their transcript. So, that has implications for it.

NAVARROI do think that moving away from sort of a trend grading scale to a mathematical one that says it averages out to a 3.5, 3.5 rounds up to an A, it's an A, is the mathematical correct way to get specifics on the grades. But I think Ms. O'Neill also calls for more specifics within those details of an A or a B. I just want to quickly go back to the comment around a student that gets an A at Whitman versus maybe at Springbrook that gets an A. We have amazing teachers in every single one of our high schools. And we have amazing potential in our students, across all 25 of our high schools.

NAVARROWhat we are working towards is we actually have more assessments that are standards-aligned by having them on a quarterly basis, rather than one time or two times a year. And those assessments that are standards-aligned help everyone understand: what are the standards that students are held accountable to? And those quarterly assessments that we have count for 10 percent of the student's grade. So, those are checking points where you can assess how well students are doing, and we, as a district, can assess how all students are doing across the board in the school system.

FISHERWell, let's hear from Karen, in Bethesda. Karen has a daughter in eighth grade. You're on the air.

KARENHi, there. Yes, I have a daughter at Cabin John Middle School in Potomac, Maryland, and just around the idea of A's are not easy, at Cabin John Middle School she works very hard for A's and B's and a couple C's she's gotten. And we just look at that as a lesson learned. What do you need to do, you know, before you get to high school, so that we don't see C's in high school? But she works -- I just wanted to say she works really hard for the A's and B's that she gets.

FISHERAnd does she have the sense that other students are working equally hard for their A's, or is that a factor at all in the way she thinks about grades?

KARENYeah, I think she has some friends who are quite bright, and their parents tell them, B's aren't acceptable. We only expect you to get A's. But I think she has friends that, you know, also work hard, as well, for their grades. We also tell her -- and the principal has even said this -- middle school and high school will be the hardest education because Montgomery County is so great with education. And once you get to college, it's going to be a breeze. And he says this and I agree with it, because I went to Whitman myself. And when I got to college I was so, I don't want to say well-educated, but I had such a good foundation, that college was not easy, but I had that foundation. So, I tell that to my daughter, as well, is that high school is going to be hard, but when you get to college, you're going to be so well prepared that it won't seem as much of a struggle as maybe high school will be.

FISHERThank you, Karen. We had a teacher from Montgomery County who called in and couldn't stay on the line, because she has to teach, so she has the right priorities. But she said that the grade inflation is ridiculous. Kids don't work hard, because they game the system. We also have a 50 percent rule. If the kids do the bare minimum of work, I have to give them 50 percent of the grade. Christopher Lloyd, is that something you hear from teachers? Is that a larger problem?

LLOYDAbsolutely. We hear that from our high school folks a lot. So, you start with 50 percent. A child turns in some work, made some effort. And so, obviously, at that point, that has an impact on the grading scale. We know that kids -- there are many, many kids in Montgomery County that work very hard and work very hard with their teachers. Our goal is that we want the grades to mean something when they go to college. We want the Montgomery County that we know and have lived in for a long time to be the same Montgomery County standard today, tomorrow, next year. And our fear is that once this starts to take hold and you have this grade inflation, that the meaning of an A in Montgomery County will be lessened for those in college, in like.

FISHERChristopher Lloyd is President of the Montgomery County Education Association, the union that represents teachers in the county. We're also speaking with Patricia O'Neill, Vice President of the County School Board, and Maria Navarro, the chief academic officer for the county. And we'll continue our conversation about grade inflation after a short break. I'm Marc Fisher.

FISHERWelcome back. I'm Marc Fisher from the Washington Post, sitting in for Kojo Nnamdi. And we are talking about grade inflation, about the idea that many people are getting A's, which they're probably happy, about but some of the other folks who are in their classes are not. And some teachers and parents are also not, in part because they're worried about what happens at the other end of high school, and particularly when college admissions officers are trying to discern what an A in one student's record means compared to an A in another student's.

FISHERAnd, Maria Navarro, the Chief Academic Officer for Montgomery County Schools, one of the things that seems to drive this debate around the country is this longstanding debate about whether we are being tough enough with students, whether we're dumbing-down courses. And, obviously, this is a debate that's gone on forever, but it seems to dovetail with the discussion about grades. And so, how do you respond when parents or teachers come to you and say, hey, this is all eliminating final exams, having less distinctions among grades? This is a part of a dumbing-down process.

NAVARROWell, what I would say is when you're thinking about higher education, higher education looks at multiple measures in terms of access to the universities. It looks at, you know, the well-roundedness of a student, as well. I'll give you an example around another data point about how students are doing. We've been strategically working from the superintendent, Dr. Jack Smith, about all means all, which means that one of the data points that universities look at is SATs or ACT scores.

NAVARROAnd so we've been working around making sure that all of our students are better prepared and have more access to take these assessments that are also an important measure for getting into colleges. And what we've seen with opening the access and opportunities for students to take and prepare for these assessments is that we've seen an increase in participation of students taking the SAT, for example, as well as an overall increase in the scores that students have gotten.

NAVARROSo, I think, as educators, the goal that we want to get to is for sure making sure that a very imperfect process, which is grading, right -- as a classroom teacher, I held the majority of the control of the grade that I gave my students. And that is still the case today. And I do think that we all, as educators, have to look at this very imperfect subjective process and try to get as much information, which is what we want, about what the students know and are able to do, because we want to prepare them for their future. And I think the best method to look at that is continue to look at the performance of our students in the structures that we have provided. And we've changed quite a few rules in the last couple of years, much faster than in previous years.

NAVARROSo, we need to continue to look at what that means for students, but at the same time we need to look at multiple measures that give us multiple perspectives on how students do so that we can accurately say, yes, students understand and know these concepts of mathematics or know how to write or know how to speak or know how to digest information that they're getting effectively. Because we've looked at it a couple of different times, not just the one time sitting aspect of it. And I think higher education is starting to grapple with that, as well, as it produced graduates.

FISHERAnd we've a number of callers who are concerned about the connection between grades and effort, and the role that grades play in providing an incentive for students to work hard. Here's Jill in Montgomery County. Jill, you're on the air.

JILLHi. Yes, this is -- I used to be on the Board of Education, and I actually asked for this data in June, because I was hearing from teachers that students were slacking off in the second and fourth quarters because they calculated out how the final score would turn out. And just as they were doing with final exams and calculating out the performance they needed to get, they were doing the same in second and fourth quarters. So, the teachers were consistently teaching at their high levels across the board, but the students were not putting in the same level of effort and engagement.

JILLAnd when I asked for this data, in the memo that came back to me, it said, through the stakeholder input, the reason they supported this trend way of grading was because of the stress on students, that it would lower the stress on students. But the way you deal with the stress on students -- which is actual and real -- is through mental health supports, through better course selection and balancing your course selection, through looking at homework policies. It's not through this sort of grade approach. Because what we have, as has been pointed out, Mr. Lloyd pointed out that you have a 79.5 and an 89.5 coming out to an A, just like a student who had done a 99 and a 99 in first and second quarters.

FISHER(overlapping) Okay. Let's give Patricia O'Neill a chance to jump in here. I mean, this gets back to that question about dumbing-down, and are grades being used for that purpose?

O'NEILLCertainly, we need to make sure that grades are a pure and honest reflection of student achievement, and they're not intended as reward, nor are they punishment. But students need to know how they're doing. Teachers need to know how they're doing. Parents, administrators, and we need to give them multiple options, multiple ways of demonstrating that achievement throughout the marking period. You know, if there is a flaw in the grading system -- and I know, as a parent, my children, and we hear children, know how to game the system. Whatever system we've ever had, students figured it out. And that's -- I think it's sort of human nature.

O'NEILLBut, you know, we have a responsibility to make sure that our high school diplomas, our student achievement demonstrate and prepare kids for college, career or life, whatever it is that they choose to go on to. We need a pure and accurate representation, so that we can adjust instruction, if it's not working, to meet those kids' needs. But we all need to be on the same page.

FISHERLet's hear from Stephanie in Bethesda, who is concerned that her son has figured out a way to game the system. Stephanie, you're on the air.

STEPHANIEYes, hi. I was calling, because I recently had a conversation with my son about the way he was -- or the amount of effort that he was putting in versus his first quarter, versus his second quarter. And it appeared to me that he was not putting in as much effort. And then he went on the system to check his grades, and explained to me that as long as he got some minimal amount, he would still get an A in the class for his semester grade, and that, together with the Montgomery County retake policy.

STEPHANIEI felt like my conversation with him was, you're not going to be prepared for college if you are depending on being able to take these -- not put in as much effort in the second quarter and still get an A for the semester, because that's not how college grading is done. And I just wonder if we really are preparing our students, because the students figure all of this out. And if we actually are preparing our students, if they're not actually putting in the same amount of effort throughout the course.

FISHERThank you. We have a similar perspective from Shulamete, who writes in, saying, it isn't just about grade inflation. In college, they will have heavily weighted finals. Are these kids not being taught this important college skill if the finals have too much weight? So, make a lower percentage, but don't lose the finals. Christopher Lloyd.

LLOYDRelated to the first caller, she's absolutely right. That's what we hear from teachers around the county, is this notion that the second quarter comes around, and the effort starts to decline. We know that in finals, maybe, maybe the final weight should be changed, but there is an understanding that the final exam captures the entire course. So, regardless of whether it's first quarter or second quarter, that information is all part of that final exam.

LLOYDAnd just getting back briefly to what Dr. Navarro said earlier, grading from a teacher, you are absolutely relying upon a teacher's professional judgment. And I stake my life on that. I think the teacher's professional judgment each and every day is what drives student learning and student success. And I know that Maria would agree with me that the first and foremost data point there is the teacher. And that teacher's grade is a really valid data point. And what we want is we want a system that the teachers operate in that allows for an accurate representation of learning in that way.

FISHERLet's hear from Mary in Montgomery College for sort of the -- in Montgomery County from the college perspective on this matter. Mary, you're on the air.

MARYThank you. I just want to say that when I listened earlier to someone who said that in some cases, the high school students, if they do 50 percent of the work, you know, get passed. And it was a revelation to me, because I've noticed that pretty much no matter what I say in my syllabus, I have quite a number of students who somehow feel just that, that if they do about half, that they'll be fine. And it's a rude awakening for them.

FISHER(overlapping) And you teach at Montgomery College.

MARYI teach at Montgomery College. Yes, I do. So, it does not prepare them. That does not give them an idea of what's actually going to happen when they come into a college class.

FISHERPatricia O'Neill.

O'NEILLWell, the policy is that a student receiving a 50 percent, it is still failing. That's a pretty deep hole still to climb out of within a marking period, if you have multiple fifties. It's not about effort. I'm not sure exactly how teachers calc -- you know, but instead of being a zero, it's a 50 percent, but that is still a failing mark. I also want to point out about the final exams. You know, a college semester is basically about 12 weeks, and our marking periods are nine weeks each. So, the semester is 18 weeks, here in Montgomery County.

FISHERWe'll have to leave it there. Patrician O'Neill's Vice President of Montgomery County School Board. Maria Navarro is the Chief Academic Officer for the system, and Christopher Lloyd is President of the Montgomery County Education Association. Thanks to all of you for being here. Today's conversation on grade inflation was produced by Lauren Markoe. Our conversation on the federal shutdown was produced by Monna Kashfi.

FISHERLater this week, we'll be focusing on the opioid epidemic in the District. Has it affected you? Record a voice memo on your phone and send it to Kojo at wamu.org with the subject line: Opioids. And coming up tomorrow, we will discuss a Virginia law that would clear the way for teachers to strike. Plus, cigarette use has decreased among young people in recent years. Has vaping taken its place? We'll explore its appeal among the region's young people. Thanks for joining us. I'm Marc Fisher from the Washington Post, sitting in for Kojo Nnamdi.

On this last episode, we look back on 23 years of joyous, difficult and always informative conversation.

Kojo talks with author Briana Thomas about her book “Black Broadway In Washington D.C.,” and the District’s rich Black history.

Poet, essayist and editor Kevin Young is the second director of the Smithsonian's National Museum of African American History and Culture. He joins Kojo to talk about his vision for the museum and how it can help us make sense of this moment in history.

Ms. Woodruff joins us to talk about her successful career in broadcasting, how the field of journalism has changed over the decades and why she chose to make D.C. home.