Saying Goodbye To The Kojo Nnamdi Show

On this last episode, we look back on 23 years of joyous, difficult and always informative conversation.

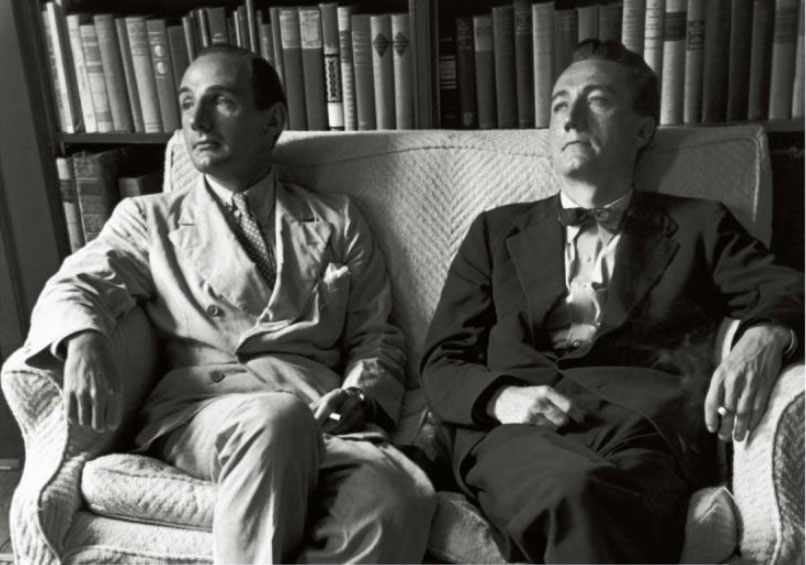

Cover image from "The Georgetown Set."

A generation of Georgetown’s influential elite impacted three White House administrations. Historian Gregg Herken explores the “Georgetown Set” that helped write history, including the Marshall Plan, Johnson’s nomination as vice president and the founding of the CIA. Legendary columnist Joseph Alsop was often the host, and guests included a sitting president – one of their own – John Kennedy, newspaper publishers, diplomats and CIA officers. Herken has studied the characters, their stories and their neighborhood’s rapid change.

Excerpted from “The Georgetown Set” by Gregg Herken, Random House 2014. All right reserved.

MS. REBECCA SHEIRFrom WAMU 88.5 at American University in Washington, welcome to "The Kojo Nnamdi Show," connecting your neighborhood with the world. I'm Rebecca Sheir, sitting in for Kojo. Coming up this hour, these days, many see Georgetown as a playground of sorts for the one percent, a hamlet in western Washington, D.C. with homes priced sky high and shops and stores where merchandise requires quite a pretty penny. But there was a time, in the 20th century, when Georgetown was the setting for the country's most serious political business.

MS. REBECCA SHEIRThe selection of a Vice-Presidential nominee, the early framework for what would become the Central Intelligence Agency. Such business unfolded over Sunday dinners, among influential people. Popular pundits, newspaper publishers, CIA officers, even a man who'd go on to become President of the United States. They were all part of the so-called Georgetown Set. Joining us to explore how Georgetown and the influential men and women who were part of it for so long helped to shape parts of America far beyond it is Gregg Herken.

MS. REBECCA SHEIRHe's the author of several books, the most recent of which is "The Georgetown Set: Friends and Rivals in Cold War Washington." He's also a Professor emeritus of American Diplomatic History at the University of California. Gregg, thanks for joining us today.

MR. GREGG HERKENI thank you. Good to be here.

SHEIRWhat images do you think of when you hear the word Georgetown? Do ideas like elite and blue blooded come to mind, or something else? And do you wish more bipartisan conversation existed today? You too can join the conversation. Give us a call at 800-433-8850. Email us at kojo@wamu.org. Find us on Facebook or send us a tweet. Our handle is @kojoshow. So Gregg, Georgetown still carries an elite kind of ring to it. I mean, the truth is, few people can afford to live there anymore.

SHEIRAnd not many businesses can afford the rent there either. But you set out in your book to tell the story of a different kind of elite class in Georgetown. People who had power and influence that went far beyond the neighborhood in the years after World War II and up through the Cold War. Who was this Georgetown Set? Paint a picture for us.

HERKENOkay, well, I'm actually, when I retired from the University of California, I wanted to write a history of The Cold War. And I did not want to write a policy history, based just upon documents. I had written a previous book about building the atomic weapons and I'd focused, in that book, upon the atomic scientists. And set upon policy issues. And I found that to be a rewarding approach. And so what I really wanted to do was a similar sort of approach with the Cold War.

HERKENAnd as a student of diplomatic history, it, I already knew that the people who lived in that six by eight block area of Georgetown, many of them had been very influential in making American foreign policy and advising the presidents and the rest of it. And this is a group of pundits, of publishers, as you said, of diplomats and spies. And in particular, there are three families that I decided to focus upon. The Alsops, the Wisners and the Grahams. The Alsops, Joe and Stewart Alsop, wrote a column that appeared in about 200 newspapers at their peak, in the mid to late 50s.

HERKENAnd this was a column that appeared four times a week, had a readership of about 25 million. And they were really among the premiere Cold War pundits. So that there was that. There was also the publisher, who lived basically around the corner, and that was Phil Graham. Phil and Katharine K. Graham. And the person who was not well known in the group was Frank Gardner Wisner. And Frank Wisner was head of covert operations, really for the very beginning, for American covert operations from the start.

HERKENIn something called the Office of Policy Coordination, that was run out of the State Department and later became the Plans Director of the CIA. And Frank is the guy, when you know about the coup in Iran in 1953 and the coup in Guatemala in 1954, that had Frank's fingerprints on it. He was head of the Plans Directorate for the agency. So, it was that group, mostly the Alsops, the Wisners, and the Grahams who were really the focus of the book. And as the book, as I continued my research, there's one figure who became really the dominant and the centerpiece of the book, and that's Joe Alsop.

SHEIRWhy don't we hear much about him today?

HERKENWell, he died in 1989, but he stopped writing his column in 1974. And he swore, after that, that he would not write about politics anymore. He didn't quite keep that promise, but, in fact, he was disillusioned with Washington, with politics. He had been a premiere hawk during the Vietnam War from the very beginning, starting in fact with Dien Bien Phu. And he had urged Eisenhower to send American aid to the French at that time. He became, he continued as a hawk, really, during the Kennedy administration.

HERKENHe urged Lyndon Johnson to send more American troops to Vietnam, as Johnson did. And Joe continued to be an advocate for expanded American involvement in Vietnam, even to the very end, even actually after the Tet Offensive in February, 1968. That he was urging that Nixon continue the battle, that he -- the phrase that was used in those days is there's light at the end of the tunnel. That is a phrase, actually, that Joe coined in a column of his in 1965.

SHEIRCan you talk about what he was like as a dinner host? He had quite the distinctive personality when he was hosting the Georgetown Set.

HERKENWell, he dominated the dinner scene, and he dominated the Georgetown salons that -- he, of course, he had a very modern house, actually, that he built at 2720 Dumbarton out of cinder block. He had designed it himself. He had it built in 1949. After it was built, the citizens of Georgetown, the Georgetown Citizens Association, lobbied Congress so that a cinder block house would not be built in Georgetown again. But he didn't care. He actually -- he wrote a column for the -- or, an article for the Saturday Evening Post called, "I'm Guilty, I Built a Modern House."

HERKENAnd in it, it was sort of a thumb in the eye of what he called Georgetown charm. He called it. He admitted that the house was a heinous offense against Georgetown charm and the neighbors agreed. And they lobbied Congress and they passed the Old Georgetown Act, which forbids cinder block houses in Georgetown. But that was the -- the house was the venue for his Sunday night suppers. And there, there'd typical, there'd be a dozen guests. Oftentimes, they would include his well-connected, so-called tribal friends. The Grahams and the Wisners.

HERKENBut also members of Congress, Senators and Congressmen. Supreme Court Justices, foreign diplomats, some rising young star in the new administration who had access to secrets of state and might spill them at the dinner table. Allen Dulles, who was later the head of the CIA. He and his wife Clover were oftentimes guests. They lived just around the corner at O Street. So, it was quite a heady group. Arthur Schlesinger Jr., as a matter of fact, talked about the power that one sensed at this dinner, to be at this dinner with all these movers and shakers.

HERKENWhen -- this was when Schlesinger was a young historian. So Joe would sit at the head of the table, and the guests said that the experience was either terrifying or exhilarating or some combination of the two. But that he would proceed with his opinion on something that -- the issue of the day. He called it the gencon, the general conversation. And he would go on at some length and then he would push -- he had horn rimmed glasses and I have a picture of this in the book, and he would put, pull, sort of pull the glasses down on his nose after he had gone at some length about some foreign policy issue or whatever.

HERKENAnd fix a particular guest with his stare. And say, so what do you think of that? And usually, they didn't know what to say, but, and if they paused at all, Joe would just continue. And he would hold on to the conversation, or the monologue, really, by a kind of droning, a hum, a hum, a hum between sentences, so that you couldn't break in anyway. So that was, that was Joe Alsop. He was a -- he was quite a figure, even though he would offend many of his guests, and actually that -- these were not, the salons were not quiet affairs. They were raucous affairs.

HERKENAnd Joe said that it was not considered an argument in the Alsop household until somebody had gotten up and stormed out of the dining room area for at least twice.

SHEIRDid that happen often?

HERKENIt happened all the time, and Joe was usually the one to do it. That he, he did not suffer fools or critics and did not distinguish between the two, I think.

SHEIRSomething you wrote in your book. It was said that the devil himself would be welcome at Joe Alsop's dinner parties, so long as Beelzebub wore patent leather shoes and kept his tail discreetly hidden under the table.

HERKENRight. There were rules that one had to obey. There was actually a book that dated from the 1930s. It was called "Social Washington." And it had a, sort of, list of etiquette. It was the -- it was de rigueur before the second World War that you followed all these rules, that you left a calling card with the hostess afterward and told her how much you'd enjoyed the dinner. And things of that sort. Joe didn't have the patience for that. He'd simply told the hostess that he was covering the Senate. He didn't have time for this sort of thing.

HERKENBut he did -- there was a certain decorum that had to be observed in the post-war dinners as well. For example, if you had to cancel out, if you were invited to one of the salons and you had to cancel out of the dinner, you didn't have someone else call. Or you didn't, obviously there was no email. You didn't text someone. You would call upon the person yourself and issue your apologies, that, your regret. And on one occasion, Henry Kissinger, when he was Secretary of State, violated that rule. He was invited, actually, to dinner at the Grahams, to K. Graham's house.

HERKENAnd Kissinger had his secretary call Kay and say he's sorry. He couldn't make it. And the next thing that Kissinger knew was the phone rang and it was Joe Alsop. And Joe Alsop upgrading Kissinger, the Secretary of State, for violating the rules, that you didn't do that sort of thing. That you needed to call yourself and not have somebody else deputized to do it.

SHEIRWe're talking post-war Georgetown now. I want to go back to when Alsop arrived in Washington in the 1930s. What was Georgetown like back then?

HERKENWell, it was a lot quieter city. A lot smaller. It was possible to find a parking place in Georgetown, I'm sure. We had the experience of looking for one yesterday, without much luck. There was not any particular journalist who was distinguished at that time. And in fact, it was probably fair to say it was a sort of pre-pundit era. That, and I have this quotation in the book about how basically the Washington journalists are a bunch of hacks who run around collecting mimeograph statements from Congress.

HERKENAnd simply file them unedited. And have no particular intelligence, no particular point of view. That was the -- at least that's the way it was portrayed. And actually, that quote is from a book that Katharine Graham had published or was writing. It was an anthology she was putting together at the time of her death. But it was about Washington pre-war, in the 30s. And Joe arrived there mid-30s, right at the height of the Depression.

SHEIRHis rent was only 125 dollars a month?

HERKENRight. And actually, it was -- Georgetown was an area where the new members of the new administration, the Roosevelt administration, Roosevelt's first term, would be able to find housing. That it was an area that had sort of fallen into neglect, and the housing was cheap at that time. And they were then, arguably, walking distance of their new jobs and the Washington bureaucracy. So it was really -- because these were people who didn't have a lot of money, they were, for the most part, young.

HERKENAnd so it was a young crowd from the start, back in those days, and I think it's fair to say that they sort of, as they, they, they stayed where they were and they became Joe Alsop's friends.

SHEIRWe're talking with Gregg Herken, author of "The Georgetown Set: Friends and Rivals in Cold War Washington." He's also Professor emeritus of American Diplomatic History at the University of California. And he has a couple of appearances scheduled during his time in Washington this week. You can check him out tonight, that's Monday, November 3rd at Politics and Prose at 7 o'clock. And tomorrow, election day, at Kramerbooks at 12:30 p.m. We're going to -- we're going to go to a break now. But do wish bipartisan conversation existed today?

SHEIRAnd do you think politicians and official Washington would be more productive if they socialized more? Join our conversation, call us at 1-800-433-8850, kojo@wamu.org or send us a tweet @kojoshow. We'll continue our discussion after a short break. I'm Rebecca Sheir, in for Kojo. Stay tuned.

SHEIRWelcome back. I'm Rebecca Sheir, sitting in for Kojo Nnamdi. We're talking with Gregg Herken about his book, "The Georgetown Set: Friends and Rivals in Cold War Washington." You can join the conversation at 1-800-433-8850, on our Facebook page, on Twitter, our handle is @kojoshow or through email, our address is kojo@wamu.org. Before the break, we were talking about Joe Alsop, who hosted much of the Georgetown set at his famous Sunday night parties.

SHEIRSo he had this big reputation around town, but few people at the time knew the truth about his sexuality. Joe Alsop was gay. What do you make of how he had this very public life, but he kept such a big part of it so very private?

HERKENWell, it's one of the -- you're asking about Washington back when. One of the sort of curious things now it seems is that a secret of that sort -- and Joe had a particular secret -- could have been kept as long as it was from the public. It's fair to say that the -- that higher circles in Washington knew that Joe was gay. But it -- that was not publicly known until after he -- actually after his death.

HERKENBut in 1961, Joe married Susan Mary Alsop who had been Susan Mary Patten and before that Susan Mary Jay. She was actually related to the first chief justice of the United States. And she was the widow of Joe's Harvard roommate, Bill Patten, who was stationed at the Paris embassy. Bill Patten died of chronic emphysema in 1916. By 1960 -- late '60 or early '61, Susan Mary was being courted by Joe Alsop.

HERKENIt was actually a campaign that took some time, but he enlisted the aid of various friends, including Arthur Schlesinger Jr. in that campaign. But she finally, in his first a sort of overture was written on airline stationery, she reminded him, and she rejected that outright. But she finally said yes, and Joe was delighted. And, Joe, at some point, told Susan Mary if she didn't know already that his sexual preference was elsewhere, so that theirs would be a platonic relationship and a partnership.

HERKENBut it was an ideal partnership, because Susan Mary was an ideal hostess to join Joe as the host of these -- the Georgetown saloons or the Sunday night suppers. And it's speculated by Bill Patten, Jr. in his own book, and I think this makes some sense, that one reason Joe married when he did is that by 1961, he was viewed as a Kennedy insider. He was a close friend, of course, of John Kennedy going back well before the election.

HERKENAnd you probably know this -- most people know the story that John Kennedy on inaugural night when he left the inaugural ball that Jackie went back to the White House, but that John went to -- President Kennedy went to Joe's house and drank champagne there until 3:40 in the morning before he went back to the White House. So he was -- he was a good friend. So Joe was known as a Kennedy insider at that point.

HERKENAnd I think he felt vulnerable to this particular secret coming out, which is the fact that he had had -- he had gone to Moscow back in 1957, his only trip to the Soviet Union. And while there, he had been ensnared in a KGB hunting trap. And basically he had been seduced by a KGB agent at the Grand Hotel. The -- in sort of classic grand dream fashion that -- and right after the Soviet agent's cowardly act that the two men burst into Joe's room, confronted him Boris and showed him pictures of the two of them together naked.

HERKENAnd immediately told Joe that he needed to cooperate with them. Joe, at that point, later wrote that he thought about the only out was really going to be suicide. But he -- instead he thought he would, as you said, play it out and to see where the game would lead. So he contacted his good friend and Georgetown neighbor who was then the American ambassador to the Soviet Union, Chip Bohlen.

HERKENAnd basically, Bohlen contacted their other good friend, Frank Wisner, who was head of the planes director at CIA. And Wisner said the only way to deal with this is for Joe to write a detailed account of exactly what happened and where it happened and to send that to -- send that to Chip, and Chip will send it to me and I will give it to Allen Dulles, the director of CIA. And that then we will -- this will pull the sting from the KGB blackmail threat.

HERKENSo effectively that's what Joe did. And the -- in fact, I have the eyes only top secret document that I got through the Freedom of Information Act from the CIA where Allen Dulles forwarded what he called Joe's confession, which ran to eight and a half pages, single spaced, of the account of what had happened in Moscow. That Allen Dulles sent that on to J. Edgar Hoover.

HERKENAnd Hoover despise both Alsops, but he hated Joe particularly because Joe, as early as -- actually both Alsops -- as early as 1946 were criticizing the FBI and were advocates of a civilian central intelligence agency to take power away from -- to make sure that Hoover would not be in charge of both domestic intelligence and foreign intelligence. So -- and, of course, the CIA was created in 1947.

HERKENSo Hoover hated the Alsops. He hated Joe in particular. Joe was always a thorn under his saddle. So he -- he -- Hoover spread word of Joe's confession. In fact, literally sent it around Washington to the highest circles. And it's fascinating that the secret did not come out until so many years later, until after Joe had died. There's a postscript to the story -- if we have time for that. And that is the pictures didn't appear publicly or it never appeared publicly.

HERKENThe pictures didn't appear in the mailboxes of Joe's friends and enemies until 1970. And suddenly in 1970 they're sent to Art Buchwald. And Buchwald was not exactly a friend, but not exactly an enemy, but he had written a play, a Broadway play about Joe Alsop called, "Sheep on the Runway." The main character is Joe Mayflower, who is clearly Joe Alsop. And Joe hated the play. It was a satire and a spoof exactly on him.

HERKENBut -- so the question was really basically, who had sent the pictures? And part of my research was to find out who had -- who had sent the pictures and who had they been sent to? And I knew that Richard Helms, who later -- at that time actually was director of the CIA, had received them and that Art Buchwald had gone to Phil Geyelin who was then the editor of the editorial -- the editor of the editorial page of the Washington Post.

HERKENAnd I'd heard from one source that they had also gone to Ben Bradlee. And actually I had interviewed Ben Bradlee in 2009 and went back to him in 2011, but I didn't find out about this that Bradlee -- the allegation that Bradlee had received the pictures as well until 2012. And by then it was too late to get an answer. So -- but I think I did find out actually who sent the photographs. It's in the book.

SHEIRWe shouldn't give that away. It is pretty amazing. I mean, this story is real-life of "House of Cards" playing out. And you are the first one to authoritatively tell it. So in terms of researching it, you were breaking new ground.

HERKENWell, there was -- from the previous book I read about it a dozen years ago about Oppenheimer, Teller and Lawrence that I realized that my favorite kind of history is biography. And the best -- and I think, frankly, the best way to tell history is biography. So I enjoyed researching that book -- the previous book so much that it took 10 years for me to finish it. It was -- I decided this one would not take that long. It took six altogether.

HERKENBut the research was just fascinating. And, of course, unfortunately, the central figures, the primary figures of the book, the Alsop -- Joe and Stewart Alsop are gone, as Frank Wisner and both Grahams actually. But the children are still around, and I was able to interview most of the children. And the Alsop family was especially nice to me, if I can put a plug in for them that they invited me to the premiere of the play, "The Columnist" and to the party afterwards that they called the Alsop Fest.

SHEIRThat's the most recent Broadway play about the Joe Alsop.

HERKENThat's the most recent -- yes, "The Columnist," which -- April 2012 with John Lithgow in the -- in the role. So the -- so I was able to interview a number of the people of the -- really, the children of the Grahams, the Alsops, the Wisners and others. And that they also provided documents that are not in Joe's papers at the Library of Congress. And I used those papers in the book as well.

SHEIRI'm talking with Gregg Herken, the author of "The Georgetown Set: Friends and Rivals in Cold War Washington." Join our conversation at 1-800-433-8850 or kojo@wamu.org. And indeed we got an email from Karen in Bethesda who writes, "How would you compare the ruling class of the Georgetown Set to the clans that are so much a part of today's politics? It may not be the Georgetown class anymore, but it seems way too much about political scene today is about small tribes of people like the folks who hang around the Bushes and Clintons, for example." Gregg, how would you respond to that?

HERKENWell, I guess, first off, the major difference I would say between Washington and Georgetown back then and Georgetown now is that people back then, even on opposite sides of the political spectrum would talk to each other and even party together. And that -- that seems, you know, that kind of division into other groups, which are special interest groups I think more often than not, that's one major change.

HERKENAnd, of course, the other change that's part of that is that the Georgetown Salon just went away, that there was an article written some few years back by Sally Quinn who talked about how power has been supplanted by money in Georgetown and in Washington and basically you don't have the political salon anymore, you have the fundraiser. The fundraiser has one purpose and one purpose only.

HERKENAnd typically, the people who are going to be going to that fundraiser are going to be from one end of political spectrum or the other. So I think altogether Washington and Georgetown in particular is certainly worst off because the salon that had been the case back in the '50s, '60s and actually Susan Mary carried them into the '70s. But that's all over. And you don't have the kind of spectrum of views that in a political party or in a social gathering, I should say, that you had back then.

SHEIRWell, the final chapter in your book is titled, "We're All So Old or Dead: The End of the Georgetown Set" and you've been talking about how it came to an end. Who's quote is that, we're all so old or dead?

HERKENThat was actually Susan Mary Alsop. And Susan -- I can't imagine anybody being married to Joe Alsop for very long, frankly. But she was for such -- she stuck it out for some length. And it must have been a really interesting dinnertime conversation between the two of them. But she finally left, moved out and divorced Joe, even though they remained friends. And they used to walk around Georgetown together as a matter of fact, and look at where everybody had lived back then.

HERKENJoe lived -- died in 1989. I don't quite remember now when Susan Mary passed away. But she was sort of the last -- last of the old guard of the Georgetown Set. And she was actually giving parties and sort of hosting salons until pretty much the very end. She was -- she also wrote her -- several books, including one about diplomatic and court life in Europe at the turn of the century, and published her letters that she and Marietta Peabody, who was another Georgetowner and friend of Joe's, wrote to each other in the 1940s and up to the 1960s.

HERKENAnd finally, she was an editor for Architectural Digest and contributed -- was contributing to the digest articles about Georgetown actually, including the Wisner's house when it was purchased and remade, remodeled that would be back in the late '70s.

SHEIRYou mentioned how part of demise of the Georgetown Set was the shift and emphasis from power to money. What role, though, did Watergate and Vietnam play in the breakup of that group?

HERKENWell, Joe would actually say that -- tell another reporter that Vietnam ruined his health and his career and his finances that he, as I think I mentioned earlier, he had been an early hawk on Vietnam. And he was anomalous in continuing to be a hawk on Vietnam among journalist. I think Harrod K. Smith was the only other journalist who continue to be so hawkish and to urge and create -- and continued at the war. So that -- that I think was what -- really ruined Joe's career was his position on Vietnam.

HERKENAnd, in fact, that he -- it was -- he sort of became a one-note Johnny on that issue. His columns continued to be we can win in Vietnam, victory is possible. There's light at the end of the tunnel. And the country just didn't believe it and the country was moving on. There were other soulful currents going on, including issues about gender equality and race relations. And Joe didn't really address those.

HERKENSo his column became less and less popular. I remember actually coming to Washington in 1971 when he was still writing the column and being upset of what he was writing. But they became less and less popular, more and more newspapers actually dropped the column. Stewart had died of leukemia back in 1974. Joe -- it was interesting on Watergate that Joe kept on urging or telling Katherine Graham that you're following a story to a dead end with Watergate.

HERKENThat there really isn't anything there. It was a third rate burglary. And the reason was that Joe's sources were basically people within at the top level of the Nixon administration. Henry Kissinger, Nixon himself, and they were not telling him the truth. So this -- I use that in the book as an example of the problem with access -- so-called access or elite journalism is if you're only talking to the people you're reporting on, you're not going to get the true story.

HERKENSo he was very late in -- he'd later admitted -- very late in recognizing the seriousness of Watergate and later apologized to Kay Graham and said in his last column that Woodward and Bernstein had performed a vital service and have done something that I wish I had -- I had done.

SHEIRWow. The fact that he was so opinionated in his columns, especially in the later years, early on in your book you mentioned that Joe and Stewart wrote, "Being a newspaper columnist is a little like being a Greek chorus," which to me means you'd be sort of more neutral commenting on something. But no? what did he mean by that?

HERKENNo, well, I -- well, I think he was thinking of the Greek tragedies where the choruses and back sort of moaning and saying, look out, trying to warn the protagonist that the end is coming, you know, don't do that because it's not going to end well. And that was the -- that was another part of -- I guess their initial appeal is that from very early on they warned about the danger of Soviet expansionism. And they had some very prophetic articles.

HERKENThey wrote about, you know, the coming nuclear arms race with the Soviet Union. They wrote one -- an article for Saturday Evening Post called, "Your Flesh Should Creep About What A Nuclear War Might Be Like." That was really spot on. So -- so there's that.

SHEIRThere's the Greek chorus, and then there's Cassandra where they've looked at as being not welcome with their prophecies?

HERKENThere -- well, they were nicknamed all Doom and Gloom, you know, the brand -- I think the Brothers Cassandra, as a matter of fact. Joe, I think, was called Ole Black Joe because his view was so dark about what was coming, about how things were going to work out with the Russians, and then the Cold War. That one critic said that their column, which was called Matter of Fact, should actually be called, For Whom the Bell Tolls, because it -- it was so predictive of how things were going to fall apart.

HERKENAnd in -- as I say, Joe's negativism. Susan Mary even wrote one of her letters to Marietta Peabody about this, you know, just come back from visiting Joe. This was before they were married. And, you know, you're so negative, it just, you know, just depresses the hell out of me and, you know, how can anybody read this stuff. You want to go slit your wrist. And Joe was kind of consistently negative on that and felt -- well, his real trend, I think at the end he becomes a tragic figure, frankly, because of Vietnam.

HERKENThat the world and the country sort of passes him by while he's still sort of on the soapbox. And that's -- that's reflected actually in "The Columnist," the last scene...

SHEIRThe Broadway show.

HERKENThe Broadway show, you know, "The Columnist," the last scene, John Lithgow as Joe was seated after the Kennedy assassination and Joe was seated at his typewriter, past deadline without any idea of what to write. And the lights go down.

SHEIRWow.

HERKENKind of sad.

SHEIRVery sad.

HERKENYeah.

SHEIRWe're going to head to the phones now. We have Dan calling. Dan, go ahead please.

DANHi. Yeah, so fascinated by this. I came across a book by Joseph Alsop which was a very odd martini diet cookbook, which apparently was sort of a bestseller. It was called, "Drink, Eat and Be Thin." And apparently, you know, was a bestseller of some sort. And was just kind of, I mean, it -- I guess it said something about sort of that era. It purported that it was possible to eat, you know, a dry martini, asparagus, hollandaise sauce, sirloin steak, Roquefort cheese, kirsch and a half bottle of claret. You could eat that dinner and lose weight.

HERKENThat was early protein diet, I guess.

DANYes, yes. Yeah, in 1965, that's when it came out.

HERKENWell, Joe, that's a good point. The -- Joe had been, I think weighed 250 pounds when he was a Cub reporter for the Herald Tribune. And he ballooned up. And he would periodically go on a binge diet and lose weight. And finally, it worked. And he became reasonably thin, but -- and it must have been the martinis because he certainly drank a lot of them.

DANRight.

HERKENI remember just -- I've interviewed some of the children who remember being taught by Joe how to mix the right martini. And he would -- and they were teenagers at the time. I'm sure they were underage, but he would mix the martini and it was not -- and he'd taste it. No, that's not quite right. So he would finish it off and then he would mix another one. And the amount of alcohol -- they -- another -- actually a daughter of Stewart Alsop said that Stew would come home from Newsweek -- he was writing a column then.

HERKENAnd he would -- he would come in the door and he'd have, you know, one drink. Sort of, you know, just after he changed. And then he'd have a drink before he read to the children. And then there would be wine with dinner. And then, you know, something after dinner. And then there would be a nightcap. And then sometimes he would write his column. So how -- I have no idea how people functioned on that amount of alcohol. And I haven't tried it, but…

DANAnd that it was for a dietary health, of course.

HERKENWell, it apparently worked because both Joe and Stew were pretty trim.

SHEIRWell, Dan, thanks for calling.

DANSure.

SHEIRAll right. We're going to head to a break now. We're talking with Gregg Herken, author of several books. The most recent being, "The Georgetown Set: Friends and Rivals in Cold War Washington." How do you think the nature of power in D.C. has changed since the days influential politicians, journalists and activists would socialize regularly in Georgetown salons? Join our discussion at 1-800-433-8850. Or send us an email, kojo@wamu.org. We'll continue our conversation in just a minute. I'm Rebecca Sheir sitting in for Kojo. Stay with us.

SHEIRWelcome back. I'm Rebecca Sheir sitting in for Kojo Nnamdi. We're talking with Gregg Herken about his new book, "The Georgetown Set: Friends and Rivals in Cold War Washington." If you would like to join us, give us a call at 1-800-433-8850, send an email to kojo@wamu.org or send us a tweet. Our handle is @kojoshow.

SHEIRAnd we did get this email from Ian, in Washington. "Joe and Mary Alsop sound like the real-life Frank and Clare Underwood, in "House of Cards." Just substitute a journalist for a congressman. What do you think of that, Gregg? You watch the show, right?

HERKENYeah, I do, yeah. Well, actually that's an interesting comment. I think it probably -- the difference between Joe and Susan Mary's life in Georgetown in the '50s and early '60s and -- and I can't remember the name of the characters now, but the characters in the more recent show is that -- is sort of indicative of the difference between the ethics, I think, of the time. That you don't have -- back in Joe and Susan Mary's day you don't have people pushing other people in front of trains.

SHEIRThat was a spoiler alert for Season Two by the way, if no one has seen it.

HERKENOh.

SHEIRGo on.

HERKENOh, I thought that happened in Season One. But anyway, well, I think, more than one. Well, anyway, so yeah, so that there's that. And Frank…

SHEIRFrank Underwood, yeah.

HERKEN…Underwood, yes, is certainly a dark figure, obviously. And there is no such dark figure I can think of that is all -- at all equivalent with the -- in Joe's circle of friends or even enemies, for that matter, with the possible exception of Lewis Strauss, who was the A.C. -- the chairman of the Atomic Energy Commission back then. And who was an inveterate enemy, along with J. Edgar Hoover, of Joe Alsop.

SHEIRSo they were power players like the Underwoods, but with the Underwoods it seems like everything is much more underhanded. At these salons things are out in the open.

HERKENThe salons were out in the open, but -- well, not entirely. I mean, there was Joe's secret sex life. There was the -- it was assumed -- actually it's been written as speculation that because Joe was a good friend of John Kennedy, that John Kennedy had gone to Joe's house in Dumbarton. Actually, he would go there typically about every fortnight, Joe said. Either with Jackie or without. But that oftentimes he would go without Jackie.

HERKENAnd it's thought that that was used -- Joe's house was used as sort of the site for his -- for Kennedy's assignations, his affairs. And I personally don't think that's true because Joe was a good friend, actually, of Jackie Kennedy, as well. And in Joe's papers at the Library of Congress you have Jackie's notes, handwritten notes on her light blue stationery to Joe, thanking him for the advice that she is getting him on various issues, including actually on the whether -- on the issue of whether or not her husband should run for the presidency.

HERKENAnd she writes in one note, "Joe, I owe you so much. I thank you so much for giving me that advice. You had told me that it's the only game worth the candle." And this is when -- this is written from the White House now. "And I realize that's the case." And Joe would give advice like when Jackie was pregnant that he would -- he wrote to her and said, "I think that you need to sort of show a bit of the common touch, that you should get your maternity dresses not from Givenchy, but from Bloomingdales."

SHEIRFashion and shopping advice.

HERKENYeah, that Joe oftentimes gave.

SHEIRBefore the break we mentioned Ben Bradlee, a former executive editor of the Post, who oversaw the paper's prizewinning coverage of the Watergate scandal. Can you talk more about his involvement with the Georgetown set?

HERKENWell, of course he was just a few doors down from John Kennedy's house on N Street. That's when Ben and Tony lived there, Tony Pinchot. And they -- of course he had an in with Kennedy, and he was, at that time, working for -- was the bureau chief for Newsweek. And was able, I think, to have -- to get certain scoops, as matter -- even though I think Ben denied that in his memoirs -- that I think that he was able to get certain information from Kennedy that Kennedy didn't give to other journalists.

HERKENHe was actually included in those salons at Joe Alsop's house. And Bradlee told me that he was flattered and surprised because he was a junior reporter, basically, at that time. He was not in the same circle. And this was when he was married to his first wife. He was not in the same circle, but he was still invited to the salons. And he thought that that was awfully nice of Joe. So Joe became a friend of his. And Bradlee even went -- 1956, Joe would have these what he called polling expeditions, where he would go out into the field and sort of see the temper of the electorate.

HERKENAnd Bradlee went with him on one occasion. They went to farms. It was a cold fall. And they went to farms in Minnesota. And Bradlee told me that Joe was dressed in a Bespoke suit, basically, with hand-lasted shoes from Fields of London. And they would walk into the fields or whatever and Joe would have his walking stick with him. And he would prod one of the farmers with his stick and say, "So what do you make of it, old boy?"

HERKENSo -- and the farmers didn't know what to think. So Bradlee was certainly fond of Joe, but not in -- and not really in the inner circle in the same way as with the -- in terms of the Alsops, the Wisners and the Grahams.

SHEIRLet's go back to the phones now. We have Alex calling. Alex, you're on the air. Go ahead, please.

ALEXWell, I was just calling to give you a little experience I had with Joe Alsop when I was driving a taxicab in Washington, D.C. in the '70s. I was the resident taxi driver at a bar called The Class Reunion, which is on 1726 H Street, around the corner from the White House. And the bartender waved me over to a client he had to go home and it was Joe Alsop. And he was in his cups, as it were. And on the way to his house he saw the 101st patch on my right shoulder and we started talking about Vietnam.

ALEXAnd I told him why -- I told him of the experience that I had in August of 1968, which convinced me not to reenlist and stay in the Army and stay in Vietnam. And so we had a good talk about that. I explained to him that -- you got time for this?

HERKENYeah, I was just curious, actually, if -- Joe never changed opinion on Vietnam. He basically argued that he had been right and that we should have stayed in the war. It was a tragedy for Vietnam and for America to have gotten out and to have lost the war. And I'm curious if he -- and you say this was in the '70s sometime?

ALEX'72 or '73, I think.

HERKENYeah, well, he doesn't stop writing the column until '74. And he never really admits that -- he doesn't admit that he was wrong or that he had rethought his position later on. I was curious if he said that to you, if he indicated maybe he had some doubts about whether we should have been in Vietnam.

ALEXWell, after I told him what my experience was, was that I had gone down to Da Nang to reenlist and get back in the Special Forces. And that night I spent in town at the safe house there in Da Nang. And when we went back that next morning, I think it was August 12 or August 22, the place had been hit by sappers. And what was significant, they had already policed up the American bodies, but there was still Vietnamese bodies lying around. And I asked one of the NCOs, "What's the story with these Vietnamese bodies? They got one's hand's missing."

ALEXThey explained that well they tie a grenade to their wrist and if they think they're going to be taken captive they pull the string and commit suicide. At that point I realized -- I said, "We don't have that commitment." And I told this to Alsop. I said, "We don't have that commitment. These people are willing to commit suicide." They go on suicide runs. "I'm willing to risk my life for this little war, but I'm not willing to just go on a suicide mission." And also what was significant was that there was also a body of a Han Chinese there who wasn't -- he wasn't Vietnamese.

ALEXHe was a big 6' tall guy. He, too, had a hand blown off. I said, "There's no way we're going to win this." That's what I told Alsop. I don't know what he made of it.

SHEIRYeah.

HERKENYeah, that -- well, that -- yeah, that's interesting. Ward Just, who was the bureau chief in Saigon and became a friend of Alsop's, told me that he was struck by the fact that Joe never changed his opinion, even in a personal conversation, never told him that -- indicated that perhaps he -- his -- Alsop's view on the war had been wrong at the beginning, the middle or the end. And as Ward said, that he thought that to admit that -- for Joe to admit that would mean that all his other values were wrong, too. And he wasn't prepared to do that.

SHEIRWell, Alex, thank you so much for calling.

ALEXYou bet.

SHEIRI want to go back to Kennedy, who kept up with all these folks. And once he was president. You said he went over to Alsop's, what, every fortnight?

HERKENThat -- Joe said in his memoir that, yeah, that was about how often it occurred. And there is a -- Joe was actually interviewed by a historian at the Kennedy Library long afterwards. And they -- the person raised -- said, "Can we talk about John Kennedy's sex life?" And Joe said, in effect, well, you haven't even touched on the start of things there. That, you know, that that's something I'm not going to talk about so you should just turn your recorder off and let's go out and have a drink.

HERKENBut he did indicate that he knew a lot about it. And I'm always, you know, it's too bad that he didn't have -- he didn't say more about it anyway, just for -- because at least it might have put an end to the speculation that Joe's house had been used as the place for Kennedy's affairs.

SHEIRRight. And what about Truman and Johnson? What was their relationship with the Georgetown set?

HERKENWell, Joe -- actually, first -- Joe's very first column at the end of -- actually it was the last day of 1945, and he and Stewart wrote the column. And they said that the major fact in this town today is Harry S. Truman, who has filled the White House with the smell of cheap cigars. And it sort of went downhill from there. They -- Truman and Joe Alsop did not get along. In fact, he -- Truman apparently called Joe Mister All Sop. And -- although, curiously enough, many years later -- and I saw this in Joe's papers at the Library of Congress. Joe wrote a letter to Truman saying, you know, I was wrong, you weren't really half that bad as president.

HERKENThe same thing with Eisenhower. Eisenhower and Joe did not get along. For one thing, Joe wanted members of the Eisenhower administration to have the same relationship that some of the people in Truman's administration -- but not Truman himself had -- in that they would become private or secret sources. And Eisenhower would have none of that. And he -- at one point he said, you know, Joe was the lowest snake on Earth or something of that effect. So there was a big change when Kennedy came in. And that was a boon for Joe's life.

SHEIRWe've been talking with Gregg Herken the author of several books, the most recent of which is "The Georgetown Set: Friends and Rivals in Cold War Washington." Thanks for joining us, Gregg.

HERKENThank you. I enjoyed it.

SHEIRI'm Rebecca Sheir sitting in on "The Kojo Nnamdi Show." Thanks for listening.

On this last episode, we look back on 23 years of joyous, difficult and always informative conversation.

Kojo talks with author Briana Thomas about her book “Black Broadway In Washington D.C.,” and the District’s rich Black history.

Poet, essayist and editor Kevin Young is the second director of the Smithsonian's National Museum of African American History and Culture. He joins Kojo to talk about his vision for the museum and how it can help us make sense of this moment in history.

Ms. Woodruff joins us to talk about her successful career in broadcasting, how the field of journalism has changed over the decades and why she chose to make D.C. home.