Saying Goodbye To The Kojo Nnamdi Show

On this last episode, we look back on 23 years of joyous, difficult and always informative conversation.

Guest Host: Christina Bellantoni

The Chesapeake Bay has an incredible 11,000 miles of shoreline, roughly equal to the length of the entire West Coast of the United States. But only 2 percent of it is open to the public. The rest is either privately owned or publicly owned but with restrictions on its use. We explore the push by local outdoor enthusiasts — and President Barack Obama — to create more places along the shore where the public can swim, fish and boat.

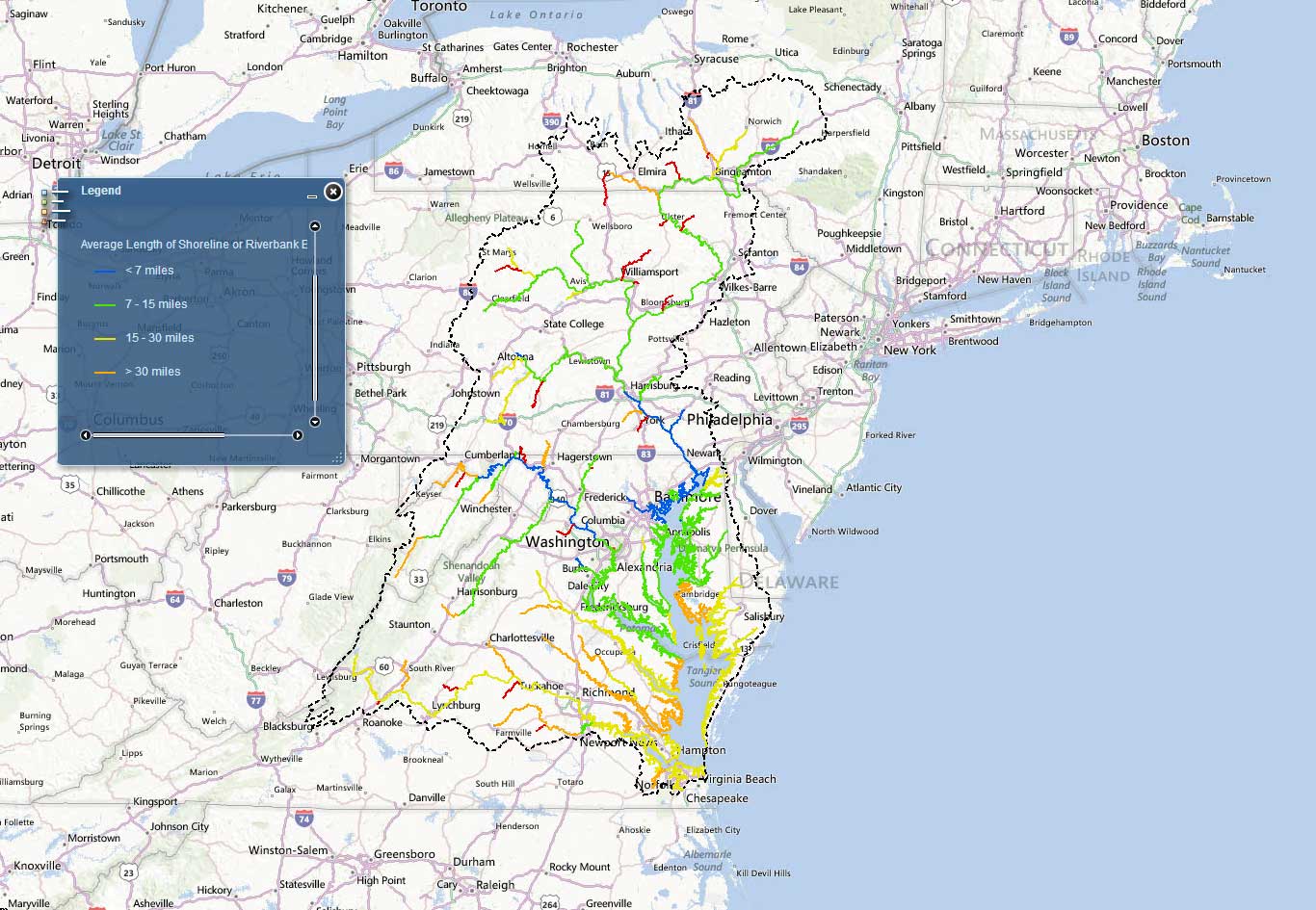

Average length of public access shoreline in the Chesapeake Bay Watershed. See detailed map.

MS. CHRISTINA BELLANTONIFrom WAMU 88.5 at American University in Washington, welcome to "The Kojo Nnamdi Show," connecting your neighborhood with the world. I'm Christina Bellantoni of the "PBS NewsHour," sitting in for Kojo. Coming up this hour, in physical terms, the Chesapeake Bay is huge. It's the largest estuary in the United States, stretching 200 miles from the Susquehanna River to the Atlantic Ocean.

MS. CHRISTINA BELLANTONIWith all its inlets and tributaries, the bay has an incredible 11,000 miles of shoreline. But if you try to get to the bay for a swim or to fish or to kayak and trying to find a spot there, that makes the Chesapeake an aloof neighbor. Only two percent of its shoreline offers public access to the water. Local outdoor enthusiasts have been trying for years to get more beaches and boat launches and trails along the shore with limited success.

MS. CHRISTINA BELLANTONIAn executive order signed by President Obama jump-started the effort, and a new bay plan aims to open 300 access points over the next dozen years. But a long history of private property around the bay and scarce funding to buy up expensive waterfront real estate make any meaningful expansion of public access a challenge. Joining me now to discuss it, very fortunate to have here in studio Jonathan Doherty, assistant superintendent of the Chesapeake Bay Office of the National Park Service. Hello, Jonathan.

MR. JONATHAN DOHERTYHi, Christina.

BELLANTONIAnd Mike Lofton. He's the founder and chairman of the Anne Arundel Public Water Access Committee, here in studio as well. Hi, Mike.

MR. MIKE LOFTONGlad to be here.

BELLANTONIThanks for joining us. On the phone, we have Charlie Stek, chairman of the Board of the Chesapeake Conservancy, a former congressional staffer to former Maryland Sen. Paul Sarbanes. Thanks for being here, Charlie.

MR. CHARLIE STEKThanks so much. This is a great show.

BELLANTONIThank you. So, Jonathan, let's start with you. The Chesapeake has 11,000 miles of shoreline -- that's a lot -- stretches from Susquehanna, all the way to the Atlantic. What -- how many places are there along that shore, and where can people get in the water?

DOHERTYWell, we've actually, over the last couple of years, looked both at that title Chesapeake, so that 11,000 miles, but also some of the tributaries flowing into it. And so we've been counting up the number of those places, and there are about 1,150 documented public access sites, which sounds like a big number. They're places that people can either fish or swim or put in a boat or a trail that provides direct access to the water.

DOHERTYBut when you stretch that number out over the 11,000 miles -- or actually the even more than 11,000 miles when you think of -- the Susquehanna reaches all the way from Cooperstown, N.Y, down to Havre de Grace, Md., that number begins to become very small, and you get big gaps in between those places.

BELLANTONIAnd looking at this map, you've got the Chesapeake going from Havre de Grace, all the way down to Virginia Beach.

DOHERTYRight.

BELLANTONISo, Charlie Stek, you've been pushing for more public access to the Chesapeake for a few decades. How did you get interested in this, and how has it put the history of land ownership around the Chesapeake, why is so much of the shoreline in private hands?

STEKYou know, it's -- I first moved down here in 1976 from New Jersey to go to graduate school. And when I finished graduate school, I had a job. I had a car. I got my car and drove all around the Chesapeake, looking for access to the water, and what I discovered is how limited access was. There's a handful of state parks that you can go to, but just very few, and distances between those are great.

STEKSo I made it a mission in my life to try and expand the number of access sites. Mike Lofton, who's on the phone, can talk about Anne Arundel County, which is close to Washington suburban area, and there's virtually little access in Anne Arundel County. But throughout the bay watershed, there's very little access. Part of the reason for that is the development pattern, so -- historically.

STEKMost of the land around the Chesapeake has been in private development, and opportunities to create parkland have been somewhat limited over the years. And so we're anxious to try and change that and anxious to grow the number of places that people can actually access the water for a variety of different recreational opportunities.

BELLANTONIWell, you've led right into my question to Mike. But first, you can join our conversation and tell us where you would like to see a public beach or trail or a boat launch on the Chesapeake Bay. Give us a call at 1-800-433-8850, email, kojo@wamu.org. Get in touch with us on our Facebook page or send a tweet to @kojoshow. So, Mike, Anne Arundel County, this is where you are a longtime resident.

BELLANTONIIt has 500 miles of shoreline just in that county. So how many public access points are we talking about there, and does the county have places where residents can get to the water? How has that changed?

LOFTONThere are certainly places where residents can get to the water, and many of them are difficult to get to. They require the visitor to get a permit. There are obstacles, whether it's physical or procedural, that make a lot of this access difficult. What we run into is things like swimming, you know, go to a beach. Well, in fact, our county doesn't have a single public beach run by our local government.

LOFTONThe state park at Sandy Point has a magnificent beach, but it frequently fills by midmorning on weekends, and people are turned away. We don't have a public boat launch, amazingly. The county with the most boats in Maryland doesn't have a public boat launch, except for the ones at Sandy Point which suffer from the same dilemma that I just mentioned regarding swimming. And there is a public launch at Truxtun Park in Annapolis, but that's not convenient for many of the people that live there. So we certainly have some access. It is inadequate to the current demand.

BELLANTONIAnd what do people end up doing instead? If they own a boat and they wanna get in the water, are they forced to go somewhere else?

LOFTONWell, they are. If you travel across the Bay Bridge to Queen Anne's County, you'll find a very impressive network of public fishing piers, boat launches and the like that the county there has developed over the last 20, 25 years. Go to the south. You can go to Calvert County or even St. Mary's and you'll find a similar set of networks. I think one of the responses has been that people don't, in fact, buy boats.

LOFTONIf you look at the statistics, we're very under-boated in Maryland. If you look at the number of boats per family and things of that sort, we have a huge opportunity to introduce a whole lot more people to boating if we were just to come up to national averages.

BELLANTONISo, Jonathan Doherty, also here in studio with us, you're with the Chesapeake Bay Office of the National Park Service. It might be unusual for our president to get involved in something like this, but in 2009, President Obama did just that, signing the executive order calling for a fresh look at public access to the Chesapeake Bay. Talk a little bit about that, why that was important and what it's doing.

DOHERTYWell, there has been a long interest in expanding public access in the Chesapeake, but it clearly has had a resurgent. We were talking -- a resurgence. We were talking earlier just a few minutes ago about some of the momentum that seems to be coming about right now, and the president's executive order helped stimulate a series of things.

DOHERTYIt brought together a number of partners to begin to identify some of the things that could advance public access and various other elements of kind of a broader strategy as well and ultimately led to a comprehensive strategy addressing a series of different aspects, and it included this goal for adding, as you said earlier, an additional 300 public access sites by 2025 and also called for developing, you know, essentially a plan or a strategy for getting there.

DOHERTYAnd because of that, and I think because of the depth of partners in the region -- both private sector folks, non-governmental organizations like the Chesapeake Conservancy that Charlie represents, county governments, state, federal partners coming together -- it presents a great opportunity for making things happen, and we seem to see some of that going on.

BELLANTONIYou know and what kind of pace do you see this at? Is it coming along on schedule?

DOHERTYWell, you know, I think, you know, we're all human beings, right? And so a time span of a decade or more is never as fast as we want it to be. We wanna see things happen now, and I think that we're on pace to make that goal, assuming that we can continue to sustain the investments that we've seen over the last couple of years. We need to do that. And there are some great success stories in a whole series of different places and different ways. But as Mike was saying, there are also a lot of gaps we still need to fill, and we don't wanna wait 13 years to do all of that. (laugh)

BELLANTONISure. And Charlie Stek on the phone with us, chairman of the Board of the Chesapeake Conservancy, as Jonathan mentioned. Charlie, how do you see the progress, and what are these bright spots that we're pointing to?

STEKWe are making progress, as Jonathan pointed out. There's a variety of new public access sites that are underway. The Chesapeake Conservancy has seven either completed or under development. We have a handful of others in the planning process. The National Park Service, with funding that has been provided through the Gateways and Watertrails program, has made a priority of funding public access sites in partnership with local governments and with partner organizations and the Chesapeake Conservancy.

STEKSo there's a variety of new access sites going in, many of which are improvements to existing sites. For example, there's a site on Rappahannock at Old Mill Park that has just been developed, that's gonna provide improved access for kayakers, for people who wanna go tubing on the river and make it easier for them to do those kinds of activities. So there's a variety of these things happening all over the watershed.

STEKWe still have very, very significant gaps. For example, very few places provide camping. So people who wanna do long-distance kayak trips and go from one point to another point, they may be able to access the water, but there's essentially no place for them to go and get off the water and camp for the night and move on to the next site. Often there's miles and miles of distances between sites where literally you'd be trespassing on private land in order to get out of your boat.

STEKAnd so we're trying to fill those kinds of gaps. We're also -- there's a huge gap in terms of swimming opportunities. Many of the sites that have been identified for future access, of the 300-plus sites that have been identified as part of President Obama's executive order, very, very few of them have been identified that allow for swimming, but none of them identified allow for camping. So there are still these broad areas where we need to make substantial improvements, and I think we're getting there. It will take some time to do that.

STEKThe Chesapeake Conservancy worked a number of years ago in 2009 with the state of Maryland on a huge acquisition of properties that have been owned by the Jesuits for nearly 400 years, 20 miles of shoreline that have been acquired, seven of which are now sort of under development called -- in an area called Newtowne Neck on the Potomac River that offer -- that can offer terrific opportunities for improved access, places for -- a beach for people to go swimming and wading.

STEKThe area has been plagued with the problem of unexploded ordnance that is now in the process of being cleaned up. But once the master plan is done for Newtowne Neck, we're gonna have a whole new area of opportunity close to the metropolitan area that people will be able to use for access.

BELLANTONIAnd we're...

STEKSo there are some very exciting things going on.

BELLANTONIAnd we're gonna talk a whole lot more about sort of the private ownership and how that all works. But make sure you join our conversation and tell us what your favorite activity is on the Chesapeake Bay. You can call us at 1-800-433-8850, email, kojo@wamu.org. Send a tweet to @kojoshow. Right now, we're gonna talk to Brian in Frederick, Md., who has a story about trying to access the water. Hi, Brian. Thanks for joining us.

BRIANHi. Hi, Kojo. I love your show. Great topic.

BELLANTONIThanks. Tell us your story, Brian.

BRIANWell, I grew up in Pennsylvania along the Susquehanna in a town called Steelton. Three miles of waterfront, and we were not allowed to go to the river. We were blocked by Amtrak and the steel mill. And we had to break the law to go fishing. You know, every time we would go fishing, we had to break the law. Railroad detectives would be after us all the time. (laugh) It was just -- it was terrible. I mean, it's still like that to this day there. You would have three miles of such lovely river, and you couldn't get to it.

BELLANTONIThank you, Brian. Appreciate it. So, Mike Lofton, is this sort of a common experience for people to have?

LOFTONWell, I've been threatened arrest -- with arrest a couple of times myself, but I was trespassing on public land at the time so -- but those are other stories. Our situation in Anne Arundel County is a little different. I'm part of a citizen group that kind of decided we needed better, and I was amazed to find so many kindred spirits of all types, you know, old guys who want to fish and launch their boats, energetic people with canoes and kayaks and stand-up paddleboards. And there's even a whole group of windsurfers that are well -organized.

LOFTONAnd one of the first things we did was compile an inventory of where are the opportunities. And it was pretty shocking to find thousands of waterfront acres, miles of waterfront already in public ownership, much of it in the hands of our local government but also some federal and some state facilities as well. So our focus has been on opening the public lands to the public.

BELLANTONIWe're gonna continue our conversation about opening up and exploring public access to the 11,000 miles of shoreline along the Chesapeake Bay. But first, we're going to take a short break. Get in touch, 1-800-433-8850. We'll be right back.

BELLANTONIWelcome back. I'm Christina Bellantoni of the "PBS NewsHour," sitting in for Kojo Nnamdi. We're talking with Jonathan Doherty of the Chesapeake Bay Office of the National Park Service, Mike Lofton, chairman of the Anne Arundel Public Water Access Committee, and Charlie Stek, chairman of the Board of the Chesapeake Conservancy, joining us on the phone. We're talking about increasing public access to the Chesapeake Bay.

BELLANTONIWe have a lot of callers interested in talking about this, finding lots of challenges to getting access to the Chesapeake Bay, so we're gonna take some of those. And you can give us a call as well at 1-800-433-8850. Always send us an email at kojo@wamu.org or a tweet to @kojoshow. Ron in Washington, D.C. owns a sailboat and has had trouble getting that out on the water. Talk about that, Ron. Thanks for joining us.

RONOh, thank you for taking my call. I have a sailboat, and I keep in on the -- at a marina in the Potomac River. And, therefore, since I pay a quite high marina fee, I've not had trouble getting to the Potomac, which is a tributary of the Chesapeake. But the Chesapeake is a national treasure, and I'm glad the president got involved because it's a national disgrace that only 2 percent of it is publicly accessible, particularly when one considers that Maryland is taxing all of its residents with increased sewage fees to help clean the Chesapeake. But 98 percent of the bay's shoreline is closed to the public.

RONSo this is, in effect, taxing the many to benefit the well-off few. And I know that at my marina and at all marinas on the bay -- on the Potomac, we pay an environmental fee, and frankly, that fee needs to be increased if the bay and its tributaries are going to be only accessible to those of us who are part of a private ownership.

BELLANTONIThanks very much, Ron, for your point. I appreciate that. So this is a great question to everybody. Why is this important? Jonathan, I'll start with you. You're with the Chesapeake Bay Office of the National Park Service. Why do people need to understand and get access to the bay?

DOHERTYWell, you know, I was thinking about it earlier today. I think there's something in our DNA that, you know, that just makes us want to be near the water. You know, we settle along the water. We wanna walk along the water. We wanna picnic along the water. You know, it's just part of who we are. And the surveys that the states in particular have done over the last decade or more just continuously show that people rank more access to the water, the development of more water trails very highly.

DOHERTYIt's consistently the highest ranked in Virginia and Pennsylvania and Maryland and the like. You know, at the same time, the demand for going out in canoes, kayaks, paddleboards is really going through the roof. So we had one survey from a couple of years ago, 2011, that showed the increase nationally in kayaking and paddle boarding and wind surfing went up by 33 percent in one year.

DOHERTYAnd so you see all of that, and at the same time, the numbers in terms of the economic benefits of outdoor recreation, paddle-based recreation, it's -- I mean, they're kind of mind-blowing numbers, the national scale of 97.5 billion that was several years ago in the Chesapeake and its tributaries. I think the economic contribution of power boating is about five billion a year.

DOHERTYSo there are a lot of reasons that people value this, and a piece of it gets back to what Ron was saying is that it's our, I don't know, physical connection with the water that also helps us support restoration efforts over the long-term.

BELLANTONISure. Mike Lofton, your thoughts on that.

LOFTONWell, I was pleased with Ron's sense of outrage because I think it's well-founded. And it's something that I see happening locally in our area. We are in the midst of implementing a stormwater management fee to deal with the number one source of pollution into the bay that comes from our jurisdiction. And it's been quite controversial. There a lot of folks who are pushing back and then don't want to pay these fees. They don't wanna pay the flush fee. And I think, at least in part, it's because they don't have that kind of a connection, that personal relationship with the Chesapeake.

LOFTONI'm a firm believer that access is essential to successful restoration, and we need to expand this army of advocates. And a way to do it is through expanded access.

BELLANTONISo, Charlie Stek, joining us on the phone, you were a staffer for former Maryland Sen. Paul Sarbanes and now are chairman of the board of the Chesapeake Conservancy. You helped pass a new law in Maryland this year that promotes new access when a bridge is built or repaired. So tell us a little bit about how that works and why that part is important.

STEKYeah. One of the easiest ways to improve public access, particularly for small crafts like canoes, kayaks, paddleboards is along the bridges that pass over waterways. And that's true throughout the Chesapeake watershed. And so we worked earlier this year with Delegate Maggie McIntosh to introduce a piece of legislation on the Maryland General Assembly, which would require the Maryland Department of Transportation to give the strong consideration -- full consideration to improving access -- waterway access whenever the state is improving a bridge or building a new bridge in the state.

STEKWe moved that piece of legislation successfully through the General Assembly. And the state is now tasked with the responsibility of developing designs and standards for that kind of access so that whenever there's a road repair project over a bridge, whenever there is a new bridge being constructed, access can be provided. I've paddled all over the Chesapeake, and in many cases, the only access is near a bridge. But often, it's very difficult. It's unsafe to access the waterway at that particular site.

STEKAnd so this will improve safety for motorists. It will provide new points of public access. And we're now working on a similar effort in Pennsylvania and hoping that the governors of the other bay states will also adopt a similar legislation.

BELLANTONIAll very interesting. One of the elements of this is where the government owns land where it's privately owned. So we've got a lot of different callers with stories about that. Steven in Baltimore City, Md. owns two acres of grassland out there. Steven, go ahead and tell us what your experience has been.

STEVENWell, I have some very nice grassland, and I'm always encouraged not to put pesticides on it or fertilizers because of the runoff and the nitrogen blooms and things like that. But I live in Baltimore City. And when I go down to the harbor, every year, just the views are being filled in by high-end condos. I -- it's to the point in which I live 15 minutes away from the water. I can't even see the water.

STEVENI'm an avid photographer. But to actually go and walk shoreline, I have to drive to Sandy Point or I have to drive to -- 15, 20 miles out just to even see the water. So the question is why should I even care for something that inherently I don't have access to?

BELLANTONIWell, let's hear from Bill in Washington, Va. with a similar issue and we'll talk about why this is important and how you deal with this issue. Hi, Bill. Thanks for joining us.

BILLHi. It's my pleasure. I love your show. I'm an artist, and I moved to Annapolis some years ago when I was looking forward to doing seascapes. And I suddenly realized after I moved there that -- I mean, I didn't move there for this but it's my hobby and I couldn't get access to the shoreline. So I thought, oh, I'll build myself a little boat. And I build a boat and I got a little trailer. And then I found out there was no place to put it in the water. And -- but the thing is everybody knows this is going on.

BILLBut I tried the West Coast for a while where they've made a lot of public access to the beaches by taking it over. The state has taken over vast areas of the oceanfront. And -- but it's pretty far away. And when you go there, you have to -- it cost you $20 to $30 a night to stay. And we're talking $1,000 a month to go and do painting for, you know, do watercolor painting for a month. And it's just, I mean, just because it's taken over by the public, it doesn't actually mean that you really get that good access in some cases. I don't know what the answer is but...

BELLANTONIWell, thank you for that, Bill. Mike Lofton, here in the studio with us, with the Anne Arundel Public Water Access Committee, you are chuckling at that.

LOFTONWell, I am because this is now the second artist that I've run on to who was looking for a -- I met an art instructor from the University of Maryland trying to find a place to take a painting class. Bill, you need to check out Beverly-Triton Beach which is just south of Annapolis. It's about 400 acres, about a mile of shoreline where the West River meets the Chesapeake. It's magnificent. And there's no -- we got them to drop the permit requirement.

LOFTONSo just drive on down there and walk on out with your easel, and I think you'll be stunned at how beautiful it is. That's been in public ownership for 25 years or more and only recently has become readily accessible to the public. Christina, I would have to add that regarding Jonathan's comment about momentum shift, I've really seen that locally.

LOFTONI've been trying for some time in our -- with our local government to get their attention about this, and really only in the last two years, our recreation and parks folks seem to be listening and listening well and have actively engaged with us. And we've identified 30 priority sites that have been visited by the park's director. We have an action plan to deliver these sites, some almost immediately, some a little bit longer term. But there's a sea change for (unintelligible)

BELLANTONI(laugh) We'll have funds. (laugh) That's excellent. Jonathan, go ahead and weigh in.

DOHERTYWell, no. I think what Bill mentioned is true. We acknowledge these tremendous gaps. There are some great examples of places you can get to. There're just not enough of them. You know, even in Annapolis, just as an example, in the early '60s, the city started an effort to turn the ends of streets -- all of the streets' dead end in the water and it's kind of a very peninsular city, and so now you have about 20 of these very small, little street-end parks where people can go or picnic.

DOHERTYThey can put in a canoe or a kayak. It's a wonderful aspect of that particular community. Is it enough? No, but there are some little vignettes and stories of places that, you know, we can build on and build from. And there are other, you know, dozens of others off the Miranda watershed too.

BELLANTONIAll good suggestions as we go into the Labor Day weekend. Makes we wanna get in the water right away. (laugh) We have an email from Steven who has emailed us at kojo@wamu.org, and he says he'd likes to see more boat docks. "As a boater, I'd like to see more access to the water on existing public land. A dock at George Washington's birthplace in Virginia is an example of a low-cost option. It's a public land so no land purchase is needed." So Jonathan's jotting that down, I see. (laugh)

DOHERTYWell, there's actually some good news. So...

BELLANTONIOh, go ahead. We can break some news right (laugh) here on "The Kojo Show."

DOHERTYWell, it's not a -- George Washington Birthplace National Monument is a lovely spot along the Northern neck of Virginia, on the south shore of the Potomac, and it's actually nearby Westmoreland State Park, and folks have been interested in that area for canoe and kayaking in particular for some time. And just within the last month or so, a longstanding beach there at the park has been opened to allow people to put canoes and kayaks in there. And the park is looking at plans for other things that could be done in terms of canoe and kayaking launches in particular.

BELLANTONIExcellent. Good news here first. Charlie Stek, on the phone with us, you're a former congressional staffer, so you obviously have seen how money can sometimes be a big problem and obstacle to making things happen. Right now you're chairman of the board of the Chesapeake Conservancy. So what is an obstacle to this access? I mean, how much does it cost to create a new public access point on the bay? Charlie Stek.

STEKThere's different kinds of access, and the kinds of access that are provided definitely affects the kind of cost. To build a concrete boat ramp obviously costs more money than putting in a soft landing for a canoe or a kayak. So the cost can vary very dramatically. We, when I worked for Sen. Sarbanes, created a program called the Chesapeake Gateways and Water Trails Program as an effort to bring some federal dollars to support local and nonprofit efforts to improve public access.

STEKAnd thanks to those dollars, there are some sources of funding available now for communities to improve public access of all kinds. There's also some federal dollars that are available to build new boat ramps within the Chesapeake, and states rely on those federal dollars, for example, to do that.

STEKWe're working with the National Park Service, with the Fish and Wildlife Service, with the Bureau of Land Management on a huge initiative right now for the fiscal '15 budget. It's called a collaborative landscape initiative in which the Department of Interior, the U.S. Forest Service and -- would make a determination, a competitive determination for preserving huge landscapes of land along five corridors within the Chesapeake watershed, which could provide new public access support in addition to conserving land.

STEKAnd I just wanted to go back, you know, one of the benefits of conserving land within the watershed not only improves the water quality, but also enables those kinds of public access areas. So the bigger picture about conserving lands and the use of these large federal dollars in preserving large landscapes also has a water quality benefit in addition to improving the connections to people and the watershed.

BELLANTONIJonathan Doherty wants to weigh in.

DOHERTYWell, yeah. I was just gonna say -- you had been asking about funding, and Charlie pointed out some of the federal sources. You know, one of the things about the Chesapeake is that there's this, again, this depth and wide range of partners. And I think we have the advantage of using multiple sources to add new access sites. I can't think of a single access site that I'm aware of that's been developed where there was one entity's money making it happen.

DOHERTYIt's almost always some combination of local donations, a foundation in some cases, state money that's generated from different pots, sometimes, some federal resources, and that's really the picture. And it takes sustaining all of those efforts and increasing them and growing them to make this partnership approach work.

BELLANTONISure. And, Charlie, you hit on conservancy, just something that Chelsea emailed us to kojo@wamu.org. She said she'd really like to see a concentration on water quality improvement in the bay. She got a bacterial infection from swimming in the bay and worries that it's too much of a health hazard for children, for everyone else to be pushing for public access. So we're gonna pick up this conversation in just a few minutes. But you can give us a call and join our conversation at 1-800-433-8850. I'm Christina Bellantoni, sitting in for Kojo Nnamdi, and we'll be right back.

BELLANTONIWelcome back. I'm Christina Bellantoni of the "PBS NewsHour," sitting in for Kojo Nnamdi, talking with Jonathan Doherty of the Chesapeake Bay Office, the National Park Service, Mike Lofton of the Anne Arundel Public Water Access Committee, and Charlie Stek, chairman of the board of the Chesapeake Conservancy, is joining us on the phone. We're talking about increasing public access to the Chesapeake Bay.

BELLANTONILots of different things to get at here, lots of questions about conservancy and where people wanna put their boats in the water and go swimming. Mike Lofton, you've got another example of a good place for public access.

LOFTONWell, we were just talking about the money problem, and no doubt that in certain cases, it is. But it's not a reason to stop. We just completed work with our local parks department and our local riverkeeper, which Jonathan talked about partners. Riverkeepers would make great partners for this kind of work, and we have the West Rhode Riverkeeper. They advanced a project to turn 65 acres of public lands that just had a gate in front of it into a public park that's gonna open in the next few weeks.

LOFTONIt's got a small parking lot, trails out to the bay front. There's a little strip of sandy beach. I've seen bald eagles in the park. It's -- and I would estimate that it cost at under $10,000 to create a small parking lot. It's virtually nothing.

BELLANTONIGood example. So we have email from Edward in Columbia, Md., asking, "Isn't it true that the law grants the public access to beaches in tidal areas up to the high tideline?" It's not really a simple yes or no answer, is it, Jonathan?

DOHERTYNo. I think generally, you can walk in the water up to the main water level, the main tideline. But you're not -- you don't have access to the beach, per se. And in some cases, particularly in some places in Virginia, not so much in the tidal section but in the upstream waters, the under the river ownership rights can be private, and you can be actually challenged in just being in the water in those cases. So it's, you know, it varies where you are. It's not an easy question to answer across the board.

BELLANTONISure. We have another emailer who actually emails in about France. His name is Kevin, and he said, "In France, that is allowed." So you can join our conversation by giving us a call at 1-800-433-8850. And Nelson in Annapolis, Md., wants to talk about a 30-acre parcel of waterfront that was purchased 15 years ago. Thanks for joining us, Nelson.

NELSONYes. I wonder if that's still not allowing any access. There's a 30-acre parcel at the end of Columbia Beach Road in Shady Side that was bought, I would say, about 15 years ago by the state and the county, Anne Arundel County. I believe that it cost $6 million. And the last time I was there -- it's probably been a year -- there was a sign on the property saying no entrance. And it's being eroded away by the activity of the bay, and it belongs to the state and the county, but no one has access.

BELLANTONIWell...

NELSONDoes someone there from Anne Arundel County, perhaps, can answer my question?

BELLANTONIThat's right. Good news for you, Nelson. Mike Lofton is here from the Anne Arundel Public Water Access Committee. Go ahead, Mike.

LOFTONNelson, you're talking about Franklin Point State Park. It's actually closer to 400 acres, and I think the price tag of about six million is right. And your call is timely. Actually, I was on the property with the ranger in charge and a couple of our committee members about eight or nine weeks ago. And there is some very simple things that could be done to provide access into the park. The Columbia Beach Road is from the north. There is another road through Shady Side called Dent Road.

LOFTONYou're gonna have to look at your Google Maps real close. But there is an existing road in there that comes up to a fence. All we really need is a simple little parking area. There is an adjacent tidal pond that could become a soft launch. The Department of Natural Resources is reviewing that right now at our request, and I expect an answer at any time that will provide us with some good access. If you wanna contact your elected official and tell him you think that's important, I think that might help.

BELLANTONIMore than news from Brooke, who emailed kojo@wamu.org. She has a recommendation for the access point. She says, "London Town and Gardens in Edgewater, Md., is a great public waterfront park. It has gorgeous gardens and historic buildings." Thanks, Brooke, for that point. We also have an email from Mori (sp?) asking about Charles County, Md., saying that, "A majority of the board of commissioners there are against preserving natural waterfront areas, instead bowing to small development lobby that wants to open up rural areas to residential development."

BELLANTONIYou know, obviously, you've got some people here who have worked with their local governments to make things happen. So first, I'll go to Charlie, who's chairman of the board of the Chesapeake Conservancy. How can we persuade local governments to get involved here?

STEKYou know, in Charles County, there's a wonderful access site to Mallows Bay that has been developed. And Mallows Bay is the site of some sunken ships -- wooden ships that were built during World War I. It's a beautiful, historic area to go paddling in, so there are opportunities. We've worked closely when we were developing the bridge access project with the state of Maryland with Charles County to identify sites that would potentially provide new access. So I think local governments are interested in this.

STEKI think they're starting to see the economic benefits of improving waterfront communities. I think having the incentives that are available, Jonathan correctly pointed out that there are some that partnerships really drive this access and demand from citizens really drive this access. So the more that people listen to your show, the more people begin to contact their local legislators and indicate that they demand new public access, and they wanna address these huge gaps, the more, I think, local government, state governments, federal government will respond to those issues.

BELLANTONIAnd if you are a local legislator, please feel free to join our conversation at 1-800-433-8850. Mark in Herndon, Va., also has a comment about a lot -- we've had a lot of people writing in, talking about overdevelopment. Mark, go ahead. Thanks for calling.

MARKThanks for taking my call. So having been a boater on the bay since the early '70s, there's been a lot of changes. But when we talk about water access and development, what often happens is that development kind of caters towards tourists, getting people in there, et cetera, and not so much towards the local population. In fact, when things get changed, often the local population get short shrifted in.

MARKAnd a couple of examples of that is, you know, one, the city center in Annapolis there -- and although that's, you know, obviously not a park land or anything, but when they went to redevelop that, they cut out the heart of Annapolis, which was really for locals, a great spot, and also a reason I went to Annapolis two to three times a year. And I haven't done so since they've essentially messed that up. But the second is the Washington Sailing Marina.

MARKWhen they changed that around many years ago to put in a nice high-end restaurant and -- et cetera, they got rid of the old sailing area where local sailors would go and relax and have a beer and a hotdog and sail and talk, et cetera. So they really overdevelopment and -- are overdeveloped then and catered towards, you know, essentially touristy kinds of things, which cuts out the benefits of local population.

MARKAnd finally, D.C. currently dumps -- I think the last assessment I heard is 300 million gallons of untreated sewage into the Potomac every year. And that is really obviously a problem for the entire bay with that kind of volume coming, A, into the Potomac and, B, into the Chesapeake Bay.

BELLANTONIThanks very much, Mark. Jonathan, do you have a response to that?

DOHERTYWell, I mean, there's a couple things here. I think, you know, the discussion of local support and community support is really what it's all about. You know, all of these access sites only happen when the community is engaged. And there's some great stories that actually relate to, you know, the issue that Mark was talking about too.

DOHERTYI'm thinking of one, along the James River. A fairly rural county, Charles City County, had developed a park a number of years ago and had this long demand for a boat dock, a boat launch for, you know, primarily for folks in the community to use. And for a variety of reasons, it hadn't happen over more than a decade.

DOHERTYAnd then kind of very rapidly through kind of a series of events that came together, including the site being along the Captain John Smith Chesapeake National Historic Trail, a series of funders came together, including the county, The Dominion Foundation, the Chesapeake Conservancy played a role, the state of Virginia, and the site opened for local communities just this past June. And, you know, so there are signs again that Mike is talking about, but it really needs to be driven by community support.

BELLANTONIAnd often developers can be in collaboration with that as well.

DOHERTYAbsolutely.

BELLANTONILots of people doing good work on that. Go ahead, Mike Lofton.

LOFTONWell, in simple terms, I think access is about politics, and all politics is local. I guess that's the other phrase. I know our group, we were fortunate to hit the time when the county was required by the state to update its public recreation plan. And we weighted in detail on that and provide them with a very specific set of recommendations about the issue of public access. And we worked, the county council and the county executive.

LOFTONAnd it was adopted in its entirety and is now part of our recreation plan, that we have a very aggressive path toward improved access. And that plan is what we're gonna trade on as we approach groups like Jonathan's and the state's natural resources people and the likes. So absolutely, you've got to engage in the planning process and get your foot in the door here.

BELLANTONIMm-hmm. We have a lot of callers who are giving us a call at 1-800-433-8850, talking about conservancy issues and trash and pollution. That's -- Sally from Reston, Va., has a comment about that. Go ahead, Sally.

SALLYYes. With increasing population, not only here but around the world, there is more and more people wanting -- demanding is the word I have to use -- access to all these various beautiful natural sites. And I truly can understand that. But I think the idea of -- we've done to Smith Mountain Lake. The water is blue green from all the old boats. It's so unsightly. And when I see water resources like that, it bothers me tremendously.

SALLYSo I think that people, fisherman, boaters, were so filled with plastic on our boats and their fishing equipment, and it gets tossed. And I think if people are going to use this property then, not only out of good will or a moral idea, but I think it should be enforce that recycling should take place, that a trash should be picked up. And I really think, not just like I say, leave it to the good will of the people, but make some enforcement. I wonder if there's any chance that your guests would comment on that.

BELLANTONIWe'll check with them in a moment. But first, we'll go to David in Herndon, Va., who has a similar comment. You do nature tours on the Chesapeake. David, go ahead.

DAVIDHey. How are you? Yes. I'm an environmental educator. And actually, I just pulled into the waterway. I'm gonna be leaving a nature tour here on (word?) boards in a few minutes. And I was really intrigued with your show. And really my comment goes along with what exactly the previous caller just said. And a part of me is actually really favoring, you know, giving more access, so that -- where you have actually more people really engaging and connecting with the waterways or the natural world.

DAVIDBut the other piece that nobody really seems to be talking about is really just the amount of littering, garbage that comes with all these increased population. And though I hear all the wonderful things that they're trying to do to be accessible, I mean, nobody is really talking about the robust programs that they're gonna implement to incurve all the litter that goes with it. So I'd like to hear one of your comments from your commentators.

BELLANTONIWell, we'll go first to Charlie Stek, who's on the phone, with the -- he's the chairman of the board of the Chesapeake Conservancy. Charlie, what do you think about all this?

STEKYou know, one of the important aspects about access is to really engage citizens into bay protection, to develop that stewardship ethic. When citizens go to Yosemite, when they go to Yellowstone, when they go to any of the national parks, they develop a love for those areas. And when they develop that kind of love for those areas, they become good stewards of the parks and of the resource.

STEKAnd we believe that by expanding public access and particularly sustainable access, passive access in many cases, I find that, you know, kayakers, canoers, people who use the access are generally some of the people who are actually doing a lot of stewardship activities in the bay. But there is an important point here. You know, this is the 30th anniversary of the Chesapeake Bay, signing of the Chesapeake Bay Agreement.

STEKIt's the 41st anniversary of the Clean Water Act, which set the very laudable goal of making our waters in the United States fishable and swimmable. And that requires a water quality component, it requires a stewardship component. And we certainly wanna do everything as part of this process to make citizens and help convince citizens that they need to be good stewards of the waterways that they're going to be using, fishing and swimming in.

BELLANTONIWell, this is all very, very interesting points. We could talk about this for sure for another hour, but unfortunately, we do not have that much more time. Just wanted to read a quick email from Kathy in Wheaton saying she'd wanna see Plum Point on the western shore of the bay, in Southern Maryland opened up. Her mother had to pay $1 for each of us to swim there in the '50s, and that still makes me mad. There's so little public access in Calvert County. We had so many people joining us. Thank you so much.

BELLANTONIBut especially thanks to our wonderful guests. In studio, here with me, Jonathan Doherty, the assistant superintendent of the Chesapeake Bay Office at the National Park Service, Mike Lofton, who is the founder and chairman of the Anne Arundel Public Water Access Committee. Thank you also for being here. And Charlie Stek, chairman of the board of the Chesapeake Conservancy. It's been a great conversation.

BELLANTONII'm Christina Bellantoni, sitting in for Kojo Nnamdi. We will be back after a break with the next hour, our discussion about some Virginia law enforcement activity and "Souvenir Nation." Tune in.

On this last episode, we look back on 23 years of joyous, difficult and always informative conversation.

Kojo talks with author Briana Thomas about her book “Black Broadway In Washington D.C.,” and the District’s rich Black history.

Poet, essayist and editor Kevin Young is the second director of the Smithsonian's National Museum of African American History and Culture. He joins Kojo to talk about his vision for the museum and how it can help us make sense of this moment in history.

Ms. Woodruff joins us to talk about her successful career in broadcasting, how the field of journalism has changed over the decades and why she chose to make D.C. home.