Saying Goodbye To The Kojo Nnamdi Show

On this last episode, we look back on 23 years of joyous, difficult and always informative conversation.

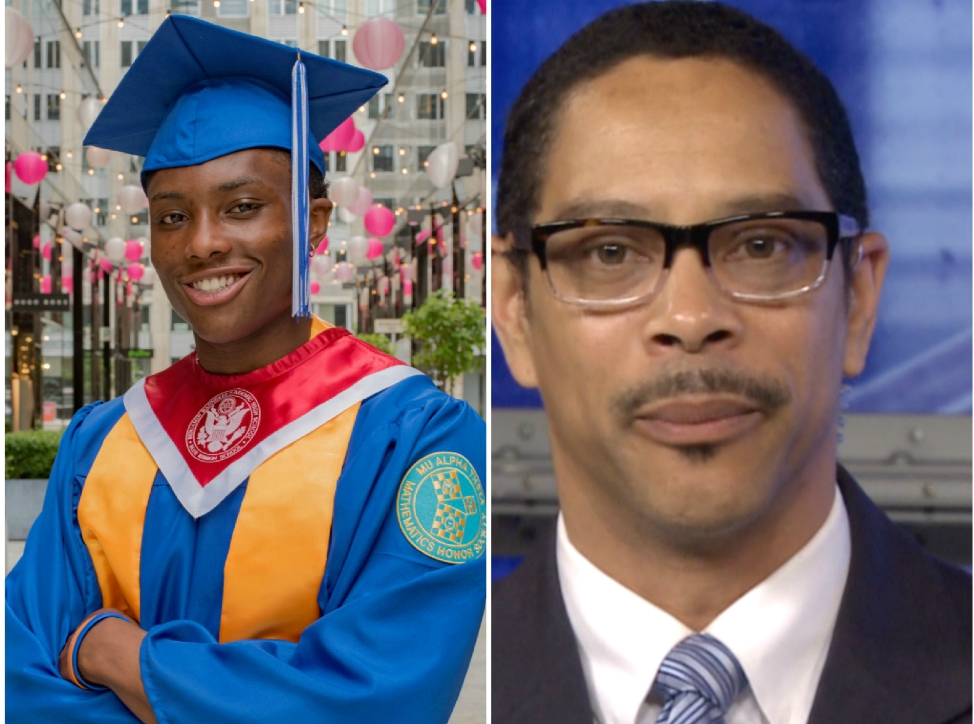

Rising Harvard freshman RuQuan Brown and WAMU Weekend Host Jeffrey James Madison.

As WAMU’s weekend host, Jeffrey James Madison’s easy-on-the-ears voice has likely filled your home or earbuds.

And you may have heard about RuQuan Brown, a student-athlete who has long worked to make his violence-prone corner of the District more peaceful. This fall he’s headed to Harvard, Madison’s alma mater.

We bring Madison and Brown together to talk about living as Black men in America — a conversation sparked by a recent piece written by James: “Here’s What I Want My White Friends To Know About My Encounters With The Police.”

James is 57. Brown is 18. These Washingtonians’ experiences with racism underline the persistence of the problem — no matter what you’ve accomplished or where you went to school. Join us.

Produced by Lauren Markoe

KOJO NNAMDIYou're tuned in to "The Kojo Nnamdi Show" on WAMU 88.5. Welcome. Later in the broadcast, will food banks run out of food during the pandemic? But first, if you're a regular listener to this station, you've surely heard the voice of weekend host Jeffrey James, who, off the air is known as Jeffrey James Madison. Last month, he wrote a piece for the Huffington Post that went viral. It was entitled "Here's What I Want My White Friends to Know about My Encounters with the Police." Many, even some of his closest friends, were surprised to hear about the racism that Jeffrey has faced over his 57 years. We wanted to find out why he's speaking up now. We also wanted to hear from a younger black Washingtonian about his experiences with racism. We reached out to RuQuan Brown, an anti-gun violence activist who just graduated from Benjamin Banneker High School and who is headed to Harvard. How has racism weighed these men down? How have they succeeded despite the prejudice they've faced? Joining me to discuss this is RuQuan Brown. He's a rising Harvard freshman and football player and anti-gun violence activist. Ru, thank you very much for joining us.

RUQUAN BROWNThank you so much. I'm extremely excited to be here and share my story.

NNAMDIJeffrey James Madison is WAMU's weekend host and the Director of Technology Services for American University's School of Communication. Jeffrey, thank you so much for joining us.

JEFFREY JAMES MADISONKojo, it's a distinct honor and a unique privilege to be a guest on your show. Thank you so much for having me.

NNAMDIJeffrey, I'll start with you. Your Huffington Post piece, entitled "Here's What I Want My White Folks to Know about My Encounters with the Police," why did you write it?

MADISONKojo, back in 2016, when this current president was elected, my staff and faculty all got together and were really supportive of me. They asked me how I was doing and how I was feeling. And I told them I wasn't feeling good at all. I was raised as a civil rights era affirmative action black man. And in this Trump era I had no idea how to conduct myself as a Jim Crow negro, and they understood that and they really supported me. But in 2020, despite the COVID pandemic shutdown and the quarantine, we were maintaining constant contact through Skype, through Teams and Zoom, but nobody was asking me that question, how I was doing, how I was feeling despite all these murders in the last three or four years, culminating with George Floyd. And it got to the point where I thought if I don't do something, if I don't express something, I might explode. So, I just sat down one right and I wrote an email. This was an email, originally. And I sent it to my colleagues at WAMU and SOC for the purpose of giving them context why somebody like me, a black man like me, is so psychically traumatized by all of this.

NNAMDIThe racist indignities you have suffered are many. But the scariest for you were those at the hands of police. Can you give us a sense of what has happened to you after being pulled over by police?

MADISONOne of the things that I discovered in writing this essay, and then having so many dozens of black men share their stories with me is the through line that there's a deliberate design when stopping black men to create humiliation, to instill humiliation. And that's what I would say is the most telling, the most permanent, the most damaging part, is that even though it wasn't my fault, somehow this humiliation got internalized, and it affected how I saw the world afterward for a long time. After the 1993 stop, apparently, I don't remember anything for days afterward.

NNAMDIWow. Well, tell us about the 1993 stop.

MADISON1993, I was driving southbound on Lincoln Boulevard in Santa Monica, California. And I passed a gas station, and I noticed that a police car got out -- pulled out and tucked in about two cars behind me. I made a left turn on Ocean Park, and as soon as I made that left turn, they lit me up, lights and sirens. So, I pulled to an area where it was clearly public and well-lit. This was near dusk. And took out my wallet. Took out my driver's license all that good stuff, and I put my hands on the ceiling as many black Americans know. This is the protocol. Hands on the ceilings and everything in sight. And for about 20 minutes, they lit up my car, the rearview and the sideview mirror, so that I couldn't see outside at all. And after about 20 minutes, when the lights came off, there standing before me was a police officer and out around me were about six police cars and a SWAT team.

MADISONAnd I was told to exit the car and step to the curb. And when I got to the curb, an officer went for his handcuffs immediately. I told him, "I'm not going to let you handcuff me. But I'll keep my hands where you can see them." And so he holstered his handcuffs, and for 10 minutes, nobody talked to me. Finally, a sergeant came up to me asked me, well, didn't ask me anything. I asked him, "Why was I stopped, and why all this?" And he told me that two black men in a red car, sports car, had been seen fleeing the scene of an attempted carjacking of a white man in a Porsche. Now, at that time I was driving when they stopped me a 1955 four-door Chevy Belair. If you can imagine what a checker cab looks like, that's what it was.

NNAMDIExactly right.

MADISONSo, bottom line is when I said to them, "This is not a sports car, and there's only me." He said, "Well, there might be somebody in your trunk." And so when I told him, "There's nobody in my trunk." And at that point was so upset by all this, I made a move toward the trunk, and when I did, 19 officers drew weapons on me. And somebody yelled, "Freeze." But as they say in ASA, they didn't have to do that, because when you hear that many hands slap leather and you hear that many guns aimed at you, it freezes you. The office took my keys from me after I shot my hands in the air, opened the trunk, saw that it was empty and within minutes they all just sort of disappeared and left me alone without any explanation, any apology and any recourse.

NNAMDIAt one point in your essay, you described the experience you had at a bank after you were accepted to Harvard and needed to send off a tuition check. Tell us what happened.

MADISONYou know, racism is comedic, at a point, sometimes to the point of tragedy. I had gone to this bank at L'Enfant Plaza to get a cashier's check as part of the deposit to go to Harvard, right? And I gave the money to the teller and asked her to issue me a cashier's check to Harvard University. And she went back typed it all out. Brought it back, and then said, "Howard University. It's a fine HPCU." But that's not where I was going. So, I said to the woman, "Actually, it's Harvard." And I spelled it out for her and she took the check. Went back, typed it up again and brought it back, Howard University again.

NNAMDIUnconscious bias, I guess, some people would call that, but it's got to hurt, at some point. Jeffrey, you're a Harvard graduated, respected voice in a major media market, entrepreneur, former television director and airline pilot. Yet these markers of success and respect don't seem to have afforded you protection of racism. Can you talk about that?

MADISONWell, I think that's what's so telling and why I needed to tell my story with my colleagues. And then when it resonated with them, they suggested I share it with a wider audience, which became the Huffington Post piece. It's that there's this sense that only a certain type of black American male is targeted by police. And the reality is it doesn't matter even if you're wearing a Harvard sweatshirt for instance, or you're driving a decent car, for instance, you are targeted. People don't see that. The police, when they make the stops, they see a black person, and that triggers something that creates a need to design a deliberate humiliation scenario.

NNAMDIRuQuan Brown, you're headed to this fall to Jeffrey's alma mater, Harvard, on a full scholarship and as a defense back on the football team. You count many blessings in your life, your family, your faith, teachers, coaches and your own talent and drive. But you've also grown up in a part of D.C. where gun violence is part of life. Can you tell us about those who you have lost?

BROWNYeah. I've lost a ton of people, specifically in the Shaw area. Back in December, I was mentoring a group of young men and woman at the Shaw Community Center. And months later, one of those students was actually murdered steps away from my house in Shaw. And so these are the types of experiences that we deal with, I deal with all the time. My stepdad was murdered in 2018. I had a teammate murdered in 2017. I just lost another teammate on Mother's Day. So, gun violence definitely hits very, very close to home. And as you spoke to gun violence prevention activism, that's why.

NNAMDIYou decided to turn that grief into action. Tell us about what you're doing to address gun violence in Washington.

BROWNSo, I created a clothing life called Love1. It can be found at love1company.com. But I created this clothing line to be proactive about ending gun violence. So, I wanted to memorialize two very important men to my, my stepdad and my teammate. And I also wanted to make sure that I'm giving, and not only raising awareness. And so what we do is take 20 percent of our proceeds and donate it to an organization that buys guns off the streets and turns it into art. Recently, we lost a young man by the name of Davon McNeal here in D.C. on Fourth of July, and we were actually able to donate very close to $10,000 to his family to help with funeral costs. So, we are using our brand, using our money to impact families before and after gun violence affects them.

NNAMDIRu, what connection do you see between racism and the gun violence that hits hardest in our majority black neighborhoods?

BROWNWell, I think that there's a lack -- in our public officials and our elected officials and in those offices and in those seats, I think there's a lack a care for just black and brown individuals in general. I think we see it in so many other areas and when we realize that our elected officials are just normal people that applied for just a different job, we realize that how normalized racism can be. One of the things that has hit me the hardest has been our own people actually internalizing racism. And that's where we find our principals, our mayors, our other elected officials, our teachers, our counselors participating in the same anti-black movements and practices as some of our white counterparts. And both of those can be very dangerous. And I think that internalized racism might be even more dangerous.

NNAMDIJeffrey, in the minute we have left in this segment, you grew up in a very different kind of neighborhood in the District. When you were six, your family moved to an upper class, majority white enclave. Tell us how you were greeted by some young white boys.

MADISONYeah. Six years old, upper Northwest D.C., Mayflower moving van pulls up. My sister and brother and I were eager for the furniture to be moved in, and five little white boys walked up and asked us if we were the "N" word. And totally shocked, but completely angered by it. I'm not even sure I knew why I knew it. I grabbed a broomstick, and I chased him down the street.

NNAMDIThat was an experience at six years old. We're going to take a short break. When we come back, we'll continue this conversation with Jeffrey James and RuQuan Brown. I'm Kojo Nnamdi.

NNAMDIWe're talking with two Washingtonians about their stories about being black and male. Jeffrey James is how he is known on the air. His full name is Jeffrey James Madison. He's WAMU's weekend host and the Director of Technology Services for American University's School of Communication. RuQuan Brown is a rising Harvard freshman and football player and an anti-gun violence activist. He is 18 years old. Let's go to the phones. He's Nassein in Washington D.C. Nassein, you are almost on the air. Now you are. Nassein, you're on the air. Go ahead, please.

NASSEINHey, how are you guys doing? Nice to talk to you.

NNAMDIThank you.

NASSEINI'm listening to the show, and all of it hits very hard to home, close to home, because I am half-black, half-Arab. I'm out of breath. I just got upstairs to my house. Yeah, being half-black and half-Arab in this country dealing with police is extremely rough. So, I'm kind of like ambiguous to the way I look. So, basically, whatever that person feels racist against is what I look like. So if they feel racist against black people, I look black to them. Against Arab, I look Arab. Even Hispanic, I look Hispanic, and I get it all the time.

NNAMDIHow about your interactions with police?

NASSEINSo, I can think of one story. It happened in Columbia Heights. I used to work at a UPS store there, and it would close a little early. So, it would an hour for happy hour. And I'd meet up with my friends Simon and Marina who are white. And my father, who is a black man, would come often and pick me up and take me home. So, on one particular occasion, he came before we were quite finished closing up the tab. So, I came up to let him know. And the closed the tab with my friends, and we all got in the car. Two seconds later, we get pulled over. And the cops are extremely rude. They snatched the keys. Smashed it on the top of the car. Talk about searching us, this and that. We're all very confused. And my father says, "No." He says, "Okay. We'll wait till the K-9 gets here." Eventually, more cops come, and we realize that what they thought they saw was some sort of deal going on because they said, "This is a high drug traffic neighborhood." And when we told that that's not the case that this is my father and these are my friends, instead of them deescalating the situation they kept at it. And they gave me father about $700 worth of tickets because he was double parked at one point waiting for me. That was a ticket. A whole bunch of nonsense. So, when my father went to dispute the tickets they weren't even registered. Like, he couldn't even pay them or fight them. And that was the last time my father ever picked me up from the bar.

NNAMDIJust an attempt to intimidate you. That's clear. Thank you for sharing your story. Ru, what about your experience with racism. Have you ever been called the "N" word or felt the police mistreated you? Or do you experience racism in a different way?

BROWNYeah. So, I experience racism all the time. And, again, the one that's most alarming for me is actually internalized racism amongst our own people, black people, because that's the least that I ever expected. And so an example I have is being at Banneker and the administration at my school discouraging me from running a business, because it is so heavily focused and emphasized that I focus on school. And I look around at so many of my other classmates and peers, especially at schools like School Without Walls or Wilson where you have a larger group of white students in there encouraged and allowed to do so much like earn their associates degree while in school or like studying abroad and things of that nature. And I think that being discouraged in those areas really sucks. Additionally, my counselor actually told me my senior year when I told her that my top three schools were Harvard, Columbia and Penn, she encouraged me to choose some schools that might actually match up with my data.

BROWNYou know, that was pretty embarrassing and pretty hurtful, actually. And not so much embarrassing for me, but it was pretty hurtful because I've been working my tail off since I was seven years old to be in this position. And to be looked at by a black woman and almost be told that I'm not good enough, it really sucked, emotionally.

NNAMDIHow many offers did you get from colleges?

BROWNTwenty-five.

NNAMDILet's talk about your dad for a minute. In December, when you were visiting an Ivy League school, your father told the football coach that he thought it was important that you not be a unicorn there. What was your father concerned about, and do you share that concern?

BROWNYeah. I definitely agree. I actually have a meeting with our mayor very soon about how we can make sure that I'm not a unicorn. And what that means is that we want to make sure other black boys and girls are sitting in Harvard and are comfortable there. We want to make sure that I'm not the only student being praised for being in this position, because it's not as abnormal as it is. We want to make sure to extend these opportunities to many, many, many more young people that have worked their butts off since a very young age, as well.

NNAMDIJeffrey, let's get back to your piece for a minute. What has the reaction been, and is the reaction of black and white people different in any way?

MADISONKojo, that's a great question. It's been phenomenal. I wrote columns for about six years as an aviation safety columnist, and if 10 to 8,000 people in a month read it, I was pleased. Within a week, over 100,000 views had seen of my piece in the Huffington Post and that was June and it keeps growing. I've gotten hundreds of people who found a way to get in touch with me and sent me their stories. Black men, in particular, by the dozens have sent me -- shared their stories with me of these painful experiences. And for me to be able to let them share their stories with somebody else aside from their families to keep it inside has really been an honor, and it's been very grateful. I've got a lot of gratitude for letting them do that and for me to be of service. A lot of white folk have also contacted me. And they break down into two interesting different demographics.

MADISONThere's about a few dozen who actually have apologized to me for what has happened to me and to other black people. And that's been very interesting and also a struggle. But then there's a whole other group of white folk who have responded and who are particularly young people -- RuQuan's age and maybe up to 30 -- who are really angry about what happened to me and are dead-set on finding some way to rectify the situation. And so I'm trying to take that energy and figure out how to use that energy that they have and sustain it.

NNAMDITalk for a minute about the Black Lives Matter movement. Has that given you any hope that this can be a less racist place to live in?

MADISONWell, what gives me hope, really, is something that my late father-in-law, George Winsor, who was on Thurgood Marshall's legal team as they brought forth the 1954 Brown vs. Board of Education case to the Supreme Court. He said, "If you to make an intractable black people problem, if you want to solve it, you've got to make it a white people problem." And the moment that Derek Chauvin murdered, publically, George Floyd in a non-Southern non-Confederate upper mid-western northern state of Minnesota on a Minneapolis street in a progressive city, he suddenly made the intractable black people of police brutality a white people problem. And I found that there are two things white to abide by. They will not abide. They will not abide being shown to the world that they are murderous, sadistic savages.

MADISONAnd the other thing, particularly young people, will not abide is the reality that equality under the law in the United States of America is really a myth.

NNAMDIRu, same question to you. Has Black Lives Matter given you hope that this nation is going grapple with racism, head-on?

BROWNI'm not quite sure about that. I think that Black Lives Matter and other young and other people that are activists can sometimes be thrown in the same pot when it shouldn't be that way. I think that there are hundreds of thousands, maybe even millions of young people that are advocating that doesn't necessarily associate themselves with a particular group, but are just eager to be activists and eager to share their testimony to bring change. And I think that's it's our young people like myself and like other individuals who are committed to making sure that their environment is a lot different than the environment that we've experienced in the past. I think it's those people that are going to be the reason why we're able to grapple with any of our issues.

NNAMDIJeffrey, in the minute or so we have left, what's your advice to white people who are wondering whether their black friends and colleagues would like them to ask about the racism they've experienced?

MADISONThat's a great question, Kojo. And I think my response is ask. Ask the question. You may be afraid, but walk through that fear, because it's worth it, because as I say in the piece -- yeah. I'll leave it like that.

NNAMDINo. We still have about 30 seconds left. How about your advice to black people who are frustrated that white friends and colleagues don't ask them about the racism they've experienced.

MADISONI would encourage them to volunteer it and ask them, "Why aren't you asking me about this?" Because without doing that, we won't get the dialogue and we won't make the progress.

NNAMDIJeffrey James Madison is WAMU's weekend host and the Director of Technology Services for American University's School of Communication. Jeffrey, thank you so much for joining us.

MADISONMy pleasure. Thank you so much, Kojo.

NNAMDIRuQuan Brown is a rising Harvard freshman and football player and an anti-gun violence activist. Ru, thank you for joining us.

BROWNThank you so much.

NNAMDIGot to take a short break. When we come back, will food banks run out of food during the pandemic? I'm Kojo Nnamdi.

On this last episode, we look back on 23 years of joyous, difficult and always informative conversation.

Kojo talks with author Briana Thomas about her book “Black Broadway In Washington D.C.,” and the District’s rich Black history.

Poet, essayist and editor Kevin Young is the second director of the Smithsonian's National Museum of African American History and Culture. He joins Kojo to talk about his vision for the museum and how it can help us make sense of this moment in history.

Ms. Woodruff joins us to talk about her successful career in broadcasting, how the field of journalism has changed over the decades and why she chose to make D.C. home.