Saying Goodbye To The Kojo Nnamdi Show

On this last episode, we look back on 23 years of joyous, difficult and always informative conversation.

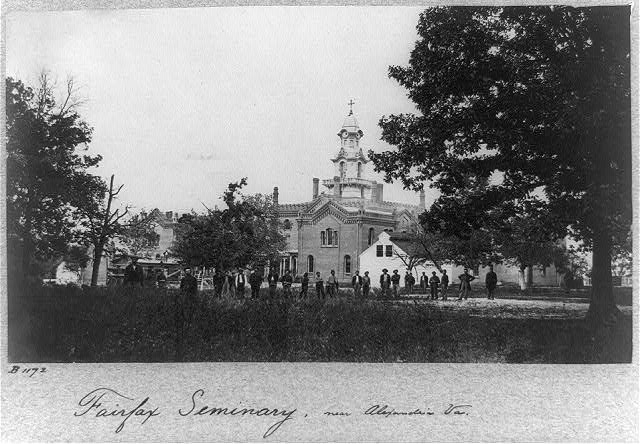

Civil War Era image of Virginia Theological Seminary featuring both Union soldiers and Black civilians. Image via the Library of Congress Prints & Photographs Division

The descendants of the slaves who built our region’s educational and religious institutions are starting to receive reparations for ancestral crimes.

Earlier this month, leaders of the Virginia Theological Seminary announced the creation of a $1.7 million endowment for reparations, recognizing its complicity in slavery.

The Episcopal school is among a growing movement of universities and religious groups seeking to reconcile and atone for their role in furthering the legacy of slavery, and segregation that continues to affect America today.

Kojo sits down with some leaders of this movement to discuss the obstacles they’ve encountered in seeking reparations — and what exactly their ultimate goals are.

Produced by Victoria Chamberlin

KOJO NNAMDIYou're tuned in to The Kojo Nnamdi Show on WAMU 88.5. Welcome. Later in the broadcast a new D.C. theater company is bringing international voices to D.C.'s arts community. We'll meet the creative director of that company. It's called ExPats. But first some of the descendants of slaves, who built our region's educational and religious institutions are starting to receive reparations for ancestral crimes. Earlier this month leaders of the Virginia Theological Seminary announced the creation of a $1.7 million endowment for reparations officially recognizing the seminary's complicity in slavery.

KOJO NNAMDIThe Episcopalian school is among a growing movement of universities and religious institutions seeking to reconcile and atone for their role in slavery and the segregation that still affects America today, but what form should reparations take and can they help address racial disparities in this country? Joining me in studio to have this conversation is The Right Reverend Eugene Taylor Sutton, Bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of Maryland. Bishop Sutton, thank you for joining us.

THE RIGHT REVEREND EUGENE TAYLOR SUTTONThank you.

NNAMDIAlso with us is Melisande Short-Colomb. She's a Georgetown University student and descendent of the Georgetown 272. Melisande, good to see you again.

MELISANDE SHORT-COLOMBIt's good to see you, Kojo. Thank you for having me.

NNAMDIThe Reverend Dr. Joseph Thomson is an Assistant Professor of Race and Ethnicity and Director of Multicultural Ministries at the Virginia Theological Seminary in Alexandria, Virginia. Joseph Thompson, thank you so much for joining us.

REVEREND DR. JOSEPH THOMPSONMy pleasure.

NNAMDIAnd Nkechi Taifa is an attorney and reparations advocate. She's Commissioner of the National African American Reparations Committee. Nkechi, always a pleasure to see you. Thank you so much.

NKECHI TAIFAMy pleasure. Same here, Kojo.

NNAMDII'll start with you, Bishop Sutton, what was the extent of the Episcopal Church's involvement in slavery?

SUTTONWell, it was much. I'm the first African American bishop of the diocese of Maryland. We came here shortly after the first Europeans came to Virginia -- when the first slaves came to Virginia in 1619. Our churches have been around largely since then. The first Episcopal bishop of Maryland owned slaves. Most of the Episcopal clergy owned slaves. Many of the resources that we have to use to do our mission and our ministries comes from wealth gained from slavery. And one thing that we just learned a long time ago in Sunday school growing up, if you steal something from someone you pay it back or you make restitution.

SUTTONIt's taken a while, but the Episcopal Diocese of Maryland in May at our annual convention said, "We want to acknowledge that and we want to help repair that." And part of that act of repair is how can we share some of the wealth that we have gained to help impoverished black communities.

NNAMDIFull disclosure here. I was raised as an Anglican and now identify as an Episcopalian, although not a very active one. Religious institutions have taken a lead in speaking out in favor of reparations. What is the responsibility of these organizations when it comes to reparation?

SUTTONWell, we need to take the lead again. The churches have taken the lead in the civil rights movement. And I would say I ask for people of good will of whatever faith and particularly as in my tradition, a Christian tradition, let's take the need in addressing and redressing a wrong that this nation never really addressed. After the civil war the proposal was made for 40 acres and a mule. That was never done. Where would be in this nation now if those freed slaves had had some benefit of the wealth that they had? We're still paying for that today in negative ways. Let's pay positively to uplift those who are still left behind.

NNAMDIJoseph Thompson, the Virginia Theological Seminary, part of the Episcopal Church was founded in 1823. Like many institutions during that time it used the labor of enslaved people. What was the seminary's specific role in slavery and in the segregation that followed?

THOMPSONYou're right to point that the Virginia Theological Seminary certainly benefited from the labor of enslaved persons. It did not actually own slaves. So it didn't engage in the buying and in the selling of enslaved persons. But we think that many of the buildings on the campus were built at least in part by the labor of enslaved persons. We know that Aspinwall Hall, which is now the main administrative building was built using the labor of enslaved persons. Certainly also much of the service work that was done on campus in the early days was done by enslaved persons as well, who were hired from local slave owners to come to campus and to do that work.

NNAMDIThe seminary has created a $1.7 million fund for reparations to the descendants of those slaves. How did the endowment come to fruition? And how will those individuals be identified?

THOMPSONSo it's coming from an outreach fund that already existed and that it was decided by our leadership that reparations was an important issue, and that we should use a good portion of that outreach fund in order to enact this reparations program. And so that is something that has come about I think because of some of the work that has been done in the larger Episcopal Church around repentance for the institution of slavery. Going back to the 2000s, there was a day of repentance for the institution of slavery. Our dean and president in 2009 issued a formal apology for slavery and for racism. And so at that kind of -- those sorts of actions and milestones helped to set off the process that lead us to where we are today. And your second question?

NNAMDIWell, how will the individual be identified?

THOMPSONThat's what we're about to work on now. Is we're going to work with local historians and genealogists in order to do that research and learn more about the people who -- as much as we can about those enslaved persons who did the work. And then, of course, to try and figure out who their descendants are.

NNAMDIYou are the Director of Multicultural Ministries for the seminary and so you'll have a role in deciding how this money will be spent. Do you know as yet how the funds will be allocated?

THOMPSONAt this point nothing is off the table. We think it will be very important to identify persons, who are descendants and then also to work with historic organizations and individuals who are in the community, because this is not just about slavery as far as we're concerned. It's also about the way that the seminary participated in the era of legal segregation after slavery. And so we want to identify some of the local institutions that are in the area and work with them as well. So it will be a conversation as we begin to identify individuals and organizations and to see what they want, what they think is proper restitution, and what their needs and ideas might be for this fund.

NNAMDINkechi Taifa, you have been an outspoken advocate for reparations since the 1960s when I first met you.

TAIFALate late '60s.

NNAMDIAnd both you and I were a lot younger. How has the conversation changed over the years?

TAIFAOh, yes. Well, it has changed dramatically. Never in my wildest dreams would I have thought that I would be in the company of some of the leading historians, scholars, politicians, religious leaders, and the academic institutions, and the like talking about this very very critical issue. So I have heartened that I always say that the seeds that I helped to plant early on maybe just maybe I might be able to sit under the shade of those trees.

NNAMDIReparations are not an entirely new concept in America or in other parts of the world. What precedent is there currently for reparations here in the United States.

TAIFAOh, absolutely. In 1988, $20,000 was paid to each living Japanese American detention camp survivor from World War II. A trust fund was established to educate Americans about the sufferings of the Japanese Americans. There was a formal apology from the United States government. And, Kojo, there was a pardon for all of those, who resisted detention camp internment. It is a sad sad commentary that the United States government has not even seen fit to formally apologize for the centuries of enslavement and post-slavery discrimination.

TAIFAThere was an apology that emanated from the House and the Senate. But the Senate apology specifically stated, "You cannot use our apology as a basis of any claim you might have for reparations." So, you know, it's just mindboggling that African people, African descendants in this country are not afforded the same type of respect and honor that other peoples have.

NNAMDIAs an indication to how long you've been working on this, talk a little bit about working closely with former Congressman John Conyers to draft a bill known as HR40.

TAIFAYes, absolutely. Well, in 1987, I helped to form an organization called NCOBRA, The National Coalition of Blacks for Reparations in America. And this was right around the time when the Japanese American Redress Bill was being passed in 1988. So Congressman Conyers was always (unintelligible) a leader of Congressional Black Caucus and a long standing member of Congress wanted to do something about this. So we as part of NCOBRA worked very closely with Conyers. What we did was strategic. What we said is that if they could do this for the Japanese Americans surely they could do this for African people in this country.

TAIFASo the HR40, the reparations bills was pairing directly off of the successful bill that had just passed. It wasn't to give one red cent to anyone. It was simply to establish a commission, a federally chartered commission to simply study the issue and to make recommendations to the Congress. And that bill HR40 to date has languished for the past 30 years in Congress.

TAIFASheila Jackson Lee took over when John Conyers retired. And at that point we as part of another organization I'm with now commissioner with The National African American Reparations Commission of which NCOBRA commission board member as well, we said, well, you know, it's been 30 years. It's 30 already. I mean, we've had Randall Robinson. We've had Ta-Nehisi Coates. We've had all of the scholars, all of the economists, etcetera, it's time for us to move beyond study and go to remedy. So we worked with Conyers and Sheila Jackson Lee to update the bill and into not just a study bill, but a bill to talk about actual proposals -- reparation proposals and remedy.

NNAMDIRandall Robinson, the founder of TransAfrica wrote a book called "The Debt." And Ta-Nehisi Coates the well-known writer wrote a very long piece called "The Case for Reparations." And before we go to the phones the following clip is from a Capitol Hill press conference with Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell explaining his stance on reparations.

MITCH MCCONNELLI don't think reparations for something that happened 150 years ago for whom none of us currently living are responsible is a good idea. We, you know, tried to deal with our original sin in slavery by fighting a civil war, by passing landmark civil rights legislation. We elected an African American president. I think we're always a work in progress in this country, but no one currently alive was responsible for that.

NNAMDIAnd Miranda couldn't stay on the line but asked, how is a payment to today's generation going to help African Americans 200 years from now? The idea of reparations baffles me. Bishop Sutton, critics of reparations argue that a national proposal would be unfair forcing white Americans to pay for the sins of previous generations. Did you get pushback within the Episcopal Diocese of Maryland when the idea of reparations was first discussed?

SUTTONOh, yes. First discussed, but we had years of educating ourselves in this issue and of making the moral argument. And to the effect that at our annual convention it was a unanimous vote, unanimous and over 90 percent white denomination, left, right, liberal, conservative, republican, democrat, rural, Appalachian, city folk, they all got it. Why did they get it? Because we know that reparations is not a transfer of moneys from white people to black people. Reparations is what this generation will do to repair the mess we've all inherited from previous generations. And also to look at our own actions as well. But reparations means to repair. Over 350 years of slavery and Jim Crow leaves damage and it needs to be repaired.

SUTTONAnd so on the one point I agree with Senator McConnell, no we are not responsible for slavery. What we are responsible for is how can we repair this mess? And so all of us need to be involved in this, recent immigrants, black, if there are reparations, I'm paying into it. And I didn't cause slavery. But I know I'm in this mess. And right now we have millions of persons of African descent, descendants of slaves, who are entrapped in a cycle of poverty, hopelessness, crime and violence. What are we going to do about that? We took wealth from them. Let's invest in these communities and put wealth back into the communities and beginning with education, schools, jobs. This is what reparations means to us as church people. And this is what we need to say to the nation, if we can do this, then why not our nation? And it may heal us all.

NNAMDIAnd I have to point out that when you say, I'll be paying for it, it is because this will be coming from the tax dollars that we pay and, of course, African Americans also pay taxes. Got to take a short break. When we come back, we'll continue this conversation and you will meet once again Melisande Short-Colomb, was a Georgetown University student and descent of the Georgetown 272. I'm Kojo Nnamdi.

NNAMDIWelcome back. We're talking about reparation and reconciliation, where do we go from here with The Right Reverend Eugene Taylor Sutton, Bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of Maryland. Melisande Short-Colomb is a Georgetown University student and descendant of the Georgetown 272. And Reverend Dr. Joseph Thompson is an Assistant Professor of Race and Ethnicity and Director of Multicultural Ministries at the Virginia Theological Seminary in Alexandria, Virginia. And Nkechi Taifa is an attorney and commissioner of The National African American Reparations Committee. Let's go to Sharon in Northern Virginia. Sharon, you're on the air. Go ahead, please.

SHARONHi, yes. My question is actually for The Right Reverend of Maryland.

NNAMDIBishop Sutton, yes, go ahead.

SHARONOkay. Yeah, my question has to do with the methodical removal of churches and their resources from congregations around the United States especially up and down the coast here. But all the way from Alabama to here in Northern Virginia and Boston as well churches have been removed from congregations and seized by the Episcopal Church. So my question is --

NNAMDIIs there a relationship between this and reparations?

MCCONNELLYeah. I'm wondering if the stealing of one thing is being used to fix the stealing of something else.

SUTTONWell, thank you for raising the issue of theft again. And that's what we're really talking about here. You're referring to an ecclesiastical matter of one group against another. But that's not really what's being addressed here. We're talking about what everybody knows is a long wealth taken out of the black community. And so when we redress that -- when we address it and try to redress some of those wrongs, what a better society we'll have. What a way that we can look at each other and say, you know, this generation tried to do something that previous generations failed us at. And let's not hand this mess down to our sons and daughters and granddaughters.

NNAMDINkechi, you've been involved as you mentioned in working with representative Congressman John Conyers on HR40. And one of the aspects of that and you mentioned it earlier was a national apology and proposal for reparation. What did you hope to achieve?

TAIFAWell, with respect to --

NNAMDIThe apology for instance, yes.

TAIFAWell, the first step to atonement is acknowledging that there was wrong. When you acknowledge that there was a wrong, a historical wrong, a continuing injury wrong then there must be just even morally I'm sorry. I'm sorry.

NNAMDIAnd talk a little bit more about what kind of opposition you faced.

TAIFAWell, again, the bill has been languishing for the past 30 years. I started on this issue when no one was taking it seriously when you would be laughed at as a lunatic or militant or a revolutionary. I proudly consider myself revolutionary, militant not a lunatic, but it was swept under the rug. Okay. So it really wasn't until the issue began to get a little bit more mainstream, mostly within the past five years with the coming of Ta-Nehisi Coates an article that people really began to looking at this issue seriously.

TAIFAWhat I really had hoped to achieve back then advocating on the issue alone is part of the healing process. It was healing for me as a young person to be able to go out there and talk about history and to articulate it and relate it to the historical world to what was going on continuing today. I work in areas of mass incarceration today. There's a direct link between mass incarceration and the massive slavery and mass incarceration, you know, today. So again, it's part of the healing process to begin to talk about these things. To seek out an apology and then once there's an apology there must be remedy.

NNAMDIMichelle emails, I think reparations should be given to African Americans descendants of slaves in the form of school grants that could be used for tuition either at the elementary schools or for college or trade schools. And that's where you come in, Melisande Short-Colomb, because in 2016 Georgetown University announced it would extend legacy admissions status to the descendants of the 272 slaves sold in the 1838 Jesuit sale. How did you learn about this part of your family heritage?

SHORT-COLOMBThank you for the question. I had a basic knowledge of my family history through the oral history of my family, knowing that my family did originate here the Maryland colony. That we had been here for some time before my family was sent south. The oral history of the family was that we were owned by an Irish Catholic family. In 2016, I found out that Irish Catholic family was the Society of Jesus, puts a different spin on things. The university itself offered legacy status, excuse me, to any qualifying student to apply for admission to Georgetown. I thought that was -- I thought I fit the bill. Having never graduated from college I applied and was accepted into the university.

SHORT-COLOMBOver the last couple of years I have sort of become part of the Georgetown family. Although our family history goes really far back, I've become part of the campus, the student advocacy group that pushed forward the referendum last year for students to add $27.20 to their tuition --

NNAMDIPer semester.

SHORT-COLOMBPer semester to start on Georgetown's campus a reconciliation fund. When we speak about repair to any group of people in America we must look at the society in which this repair is to take place. In 2019, our society in America is growing in intolerance, in the notions of white supremacy, fascism, Nazism that are not congruent with social repair. African Americans and people who are multigenerational African Americans cannot be repaired in a society in which white supremacy continues to rear its head and to become part of the national dialogue of we as Americans believe that this is our right to be racially superior here in America.

SHORT-COLOMBWho can be repaired in that general atmosphere? We are not moving forward. We are moving forward rhetorically and yet we are still being held back by common notions that are incorrect that are mythologized and that are plain and simple wrong.

NNAMDIOn the one hand Lidia emails, very specifically I've had the idea that we could have a national lottery to pay for reparations something like Powerball. Build a fund over 10 years. Determine the population that gets the money. Use some of the money for financial literacy education before the payout. Government could incentivize this by reducing taxes on winning and Americans would voluntarily fund the actual reparations through purchase of the lottery tickets not through taxes. That is as specific as a proposal as I have ever heard. There are a variety of ideas that have been battered around for years about reparations, but what we're talking about here I guess, Bishop Sutton, is the principle itself.

SUTTONYes. The principle itself. And I testified this year for HR40. I think it's a wonderful healing thing, and just thank you very much, Nkechi, for your years of work on that. You've labored when not a lot were behind you. We owe you a great debt, you and others as well. I testified before the commission, because we know that if you're happy with the state of race relations right now do nothing about this. But if you think we can do better and we ought to do better, then let's be serious about talking about restitution. And so that's why I testified.

SUTTONI even have said earlier this summer in another public place, I just threw out a figure of something. I said, five hundred billion dollars, and, of course, the crowd is just taken aback. Five hundred billion and I said, well, you know, our annual deficit is one trillion dollars. And we spend six trillion dollars in wars in the Middle East and that repaired nothing.

SUTTONAnd so when you start thinking about what would $500 billion do invested in the black community, I live in Baltimore. We have dilapidated schools there and we don't have funding. We need to pay good teachers. We don't have funding. There are persons languishing in nursing homes of African descent, who never had a chance to accumulate wealth in their life. We can do something about that and we can feel better about ourselves for having addressed it. That's why I've been passionate about this issue. It's not because of money, it's because of the moral healing that needs to happen in this country and psychological healing as well.

NNAMDIHere is Michael in Bethesda. Michael, you're on the air. Go ahead, please.

MICHAELYes. Kojo, thank you for taking my call. There was undoubtedly -- slavery was undoubtedly horrific. There are terrible lingering effects on it, terrible lingering effects. But I haven't heard an economic analysis of what these reparations would be and how they would be measured. An economist would typically look at the, but for world, you know, but for slavery what would the descendants of the slaves be making? And assuming that a few of them would have migrated or not many of them would have migrated to the United States, then they would now be residing -- the descendants would now be residing in African and they would have minimal, you know, many times less income than most of them do here. So the question is --

NNAMDIWhich Africa are we referring to? Are you referring to the Africa that was consciously underdeveloped by Europe? Are you referring to the Africa that was consciously colonized by Europe? Are you referring to the Africa from which all of the resources were taken and transferred to Europe? Is that the Africa you're referring to?

MICHAELAfrica as it exists today. I mean, you look at -- I'm just talking about -- I'm not talking about the morality. I'm talking about the economic analysis the way an economist I believe would look at it. And I haven't heard that analysis. So admittedly there are moral issues here that need to be addressed, but I don't think anybody has looked at the economic analysis.

NNAMDIWell, I'm pretty sure there are a lot of people, who have looked at the economic analysis because you should that in Ta-Nehisi Coates's arguments for "The Case for Reparations" he was not specifically pointing at slavery. He was pointing about the kinds of discrimination and exclusion that happened post-slavery. And so there's a lot to be accounted for here that economists will be taking a look at, but I do have to move on. Here is -- unless somebody else wanted to respond to our previous caller, because I was simply trying to say, sir, that the Africa that you see today is the Africa that is in the condition that it's in partially because of its interaction with Europeans. Here's Edward in Washington D.C. Edward, you're on the air. Go ahead, please.

EDWARDHey, Kojo. Yeah. You just hit on actually what my comment was going to be about. From what I've been hearing and in the media and reading it seems that the discussion on reparations is -- I don't know a bit misguided maybe a bit limited in its scope. It seems to me that the descendants of the slaves -- the development of the descendants of slaves was not economic development was not only injured by slavery itself. But also by everything that happened since slavery. I think the reconstruction was supposed address this and was aborted after two years. So it seems that if we consider the fact that reconstruction never actually got underway until 1964 then when we talk about reparations we have to be talking about everything that happened between 1865 and 1964 in addition to slavery, number one.

EDWARDNumber two, I'd address the previous caller's comment. I'd just like to point out that you can't change one historical fact. Say the existence of chattel slavery without changing everything related to it. Like the -- as you pointed out, the deliberate underdevelopment of the African continent that was attendant to it. That was dependent on it actually. If you change one, you change the other. It's important to keep that in mind. Thank you very much.

NNAMDIThank you very much for your call. Here now is Dana in Annapolis. Dana, you're on the air. Go ahead, please.

DANAYes. I was curious. When we start talking about reparations I do think that a good idea to at least start the conversation. But I also feel like we leave out other populations that have also been very sidelined such as the Native American population in America. Are there any thoughts on that? I've never really heard anybody discussing how we can fix the problems many of which are the same as would be in the African American community.

NNAMDIMelisande.

SHORT-COLOMBYes. I would like to. And I have been talking about this a little bit more, because whenever there are conversations directly related to addressing the wrongs of slavery and Jim Crow years here in America, people will say, well, we cannot have this conversation without speaking about the Indian people. Unfortunately many of the Indian nations signed agreements with colonial governments and the American governments. Those agreements were not upheld unfortunately to the detriment of Indian nations and tribes. There were also six or seven Indian nations, who were involved in slavery who actively enslaved people and who were part of slave catching and the fugitive slave laws and policing enslaved people.

SHORT-COLOMBThere were Native Americans and Indian tribes who owned black people and enslaved black people. Where are conversations in Native American groups when speaking to the government of the United States of America, do they include the black members of their tribes that were ejected as not being purely native to those tribes. So yes, there are many many different people who have suffered in the United States of America. But the laws of the land were not crafted to keep everybody down.

NNAMDIAllow me to go to Barry in Garret Park, because Gary will be talking about law. Gary, you're on the air. Go ahead, please.

GARYHi. I'm calling to suggest that there's a relevant precedent in the environmental law for reparations. The Super Fund law that was passed in 1980 created the ability to tax chemical companies for the old chemical waste dumps that existed all over the country that had, you know, these were abandoned chemical waste dumps that had been created decades and decades ago. And it was legal at the time to dump that stuff. But because the wastes constituted a continuing form of harm it was constitutional for Congress none the less to create a system of taxing the chemical industry to pay for the cleanup of these waste dumps under the Super Fund law.

NNAMDIThank you very much for your call. I'm afraid we're almost out of time, but Nkechi Taifa could tell you about a whole lot of legal precedents that would justify reparations in her opinion and in the opinion of a lot of people who also support reparations. But that's all the time we have. Nkechi Taifa is an attorney. She's a reparations advocate and she's a Commissioner of the National African American Reparations Committee. And tell them about the children's book you wrote and whose name is on there.

TAIFAOh, my goodness. Oh, the adventures of Kojo and Alma. This was a way back in the day. I'm surprised you -- well, of course you remember that.

NNAMDII'll remember it forever. What are you talking about? I'll never forget it. Thank you very much for joining us. The Right Reverend Eugene Taylor Sutton is Bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of Maryland. Bishop Sutton, thank you for joining us.

SUTTONThank you so much, Kojo.

NNAMDIReverend Dr. Joseph Thompson is an Assistant Professor of Race and Ethnicity and Director of Multicultural Ministries at the Virginia Theological Seminary in Alexandria, Virginia. Thank you so much for joining us.

THOMPSONThank you for the opportunity.

NNAMDIAnd Melisande Short-Colomb is a Georgetown University student, descendant of the Georgetown 272. Good to see you again. Thank you for joining us.

SHORT-COLOMBThank you for having me, Kojo.

NNAMDIShort break. When we come back a new D.C. theater company is bringing international voices to D.C.'s arts community. We'll meet the creative director of that company. It's called ExPats. I'm Kojo Nnamdi.

On this last episode, we look back on 23 years of joyous, difficult and always informative conversation.

Kojo talks with author Briana Thomas about her book “Black Broadway In Washington D.C.,” and the District’s rich Black history.

Poet, essayist and editor Kevin Young is the second director of the Smithsonian's National Museum of African American History and Culture. He joins Kojo to talk about his vision for the museum and how it can help us make sense of this moment in history.

Ms. Woodruff joins us to talk about her successful career in broadcasting, how the field of journalism has changed over the decades and why she chose to make D.C. home.