Saying Goodbye To The Kojo Nnamdi Show

On this last episode, we look back on 23 years of joyous, difficult and always informative conversation.

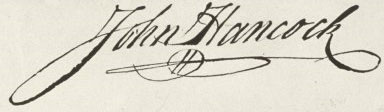

John Hancock's signature as it appears on the engrossed copy of the Declaration of Independence.

John Hancock’s may be the most recognizable: the largest signature on the Declaration of Independence and a mark of loyalty to a fledgling nation. A new exhibit at the National Archives explores the power and poignancy of signatures throughout history. Signing one’s name can be an act of authority or distinction. It can confirm an identity, deliver consent or register a grievance. We consider the many ways signatures convey meaning and values in our society and the ways technology is changing them.

Can you identify the U.S. president by his signature? From neat type to nearly illegible scrawl, the handwriting style of a president can vary as widely as his leadership manner. (All signatures courtesy U.S. National Archives)

MR. KOJO NNAMDIAffixing one's signature to a document is often an act of authority, of distinction, a way to confirm and assert our identity, signal consent or register a grievance. And in the course of our nation's history, signatures have empowered, rejected, endorsed and enfranchised countless Americans. Now, an exhibit at the National Archives exposed the power and poignancy of signatures. Joining us to share some of the stories they tell us is Jennifer Johnson. She is a curator at the National Archives here in Washington, D.C. Jennifer Johnson, thank you for joining us.

MS. JENNIFER JOHNSONThank you for having me.

NNAMDIWe ask you to join the conversation by making a call, 800-433-8850. Has your own signature changed over time? Tell us what you've noticed about it. Did you practice your signature while you were growing up? Are you happy with it now or does something about it still nag you, 800-433-8850. You can send email to kojo@wamu.org or you can go to our website where you can find a little bit of the exhibit at kojoshow.org and where you can test your own presidential signature knowledge with a quiz that you'll find at kojoshow.org. You can also join the conversation there, ask a question or make a comment.

NNAMDIJennifer Johnson, I imagine the National Archives houses more signature than we could ever count. So how did the idea for this exhibit come about?

JOHNSONIt really was a conversation with our curatorial team on how fun it would be to showcase some of the billions of signatures that you find in our holdings. And we started exploring the different themes we could do. For instance, we could do a whole signature style section and show off some of the artifacts from our holdings. We have an eye jacket that was worn by Dwight Eisenhower himself on display. We also had Jackie O's pillbox hat on display at the beginning of the exhibit. And we have a dress -- the dress that Michelle Obama the first lady wore the night that President Obama was elected.

NNAMDISpeaking of signature style, we'll talk about that later and I'll remind you that there's a photo gallery of some of the items included in this exhibit at our website kojoshow.org. And there's a link to the exhibit page that will tell you how you can visit both in person and virtually. The archives house this nation's Declaration of Independence on which we find the signature that has become shorthand for signatures all, John Hancock's. How significant was a signature at the founding of this country and how has that significance changed over time?

JOHNSONI think more than ever signatures are still important but technology has changed the way that we sign things. We're often signing credit card receipts, maybe even your mortgage documents electronically. But -- so we've probably moved a bit away from the flourish of John Hancock into different types of signatures. But this exhibit really is a chance to explore the breadth of the signatures that the National Archives houses.

JOHNSONWe have signatures from Thomas Jefferson to Marie Curry to the LA Lakers on display right now. So visitors will have a chance to kind of discover the amazing variety of records that we have.

NNAMDIWho invented the autopen? Why did the first shift come with the autopen? Why did we ever need the autopen?

JOHNSONThat's a great question. My understanding is that at least the first president to use it was President Truman. It's been in use for quite awhile. And, you know, it was used mainly as a mechanism to sign mass volumes of either correspondence or maybe invitations. And it provides a signature that is more personal than a stamp per say. So an autopen signature definitely gives you the authentic signature.

JOHNSONAnd it's actually been used more recently to sign legislation. President Obama has used it to sign legislation. President Bush, George W. Bush had the Justice Department look into the legality of using it to sign legislation. And they ruled that it would be legal. So it's been used much more recently and is still in use quite a bit on The Hill and, I'm sure, in different offices around town.

NNAMDIHow has technology -- speaking of the autopen -- changing how we sign our names now?

JOHNSONMy personal theory is that maybe we don't make them as clear as they used to be. I often think that, you know, the John Hancocks and the George Washingtons, they took great care in their signatures. It also is a status symbol for them that they were able to write. So just the nature of the signature has changed in that sense.

NNAMDIWant to get back to the fountain pen because in modern history it has been the standard for presidents to use a number of pens in completing a single signature so they can give them out as mementoes. The pens you have in this exhibit reveal that fountain pens were used until fairly recently. What's the significance of these items and a signature completed by degrees, if you will?

JOHNSONYou know, I think the -- I'm glad you brought that up because we do have -- in the gallery we have 50 signing pens representing 50 pieces of legislation that are loaned to us from the O'Brien family. The exhibit is in the Lawrence F. O'Brien Gallery. And the signing pens -- you know, often when an act is signed, they're given out as souvenirs so the president often signs his name with multiple pens. So the outcome is -- can be interesting to see.

JOHNSONFor instance, on the Voting Rights Act Lyndon Johnson's signature looks pretty scratchy because he, I'm sure, used at least a couple dozen pens to sign his name once. So it is fun to look at the different signatures.

NNAMDIAnd compare the signatures signed with multiple pens with the signature signed with one pen and figure out why they look so different? That's one of the things we can do at the exhibit?

JOHNSONSure. Yeah, you can see an example of -- with Lyndon Johnson himself, he would often put a dot under his name if it was he that had signed it. So you get to see an example of Lyndon Johnson's signature, in other words, not an autopen signature.

NNAMDIAnd at the end of the exhibit lies an autopen where visitors can get their very own John Hancock, correct?

JOHNSONCorrect.

NNAMDIThere you go. We're talking with Jennifer Johnson. She is a curator at the National Archives here in Washington. And we're talking about the signature exhibit currently taking place there, inviting your calls at 800-433-8850. Have you collected autographs or do you have a signed item you prize? Give us a call, tell us about it, 800-433-8850.

NNAMDIThe power of the pen is not limited to people in elected office in our democracy. How did petitions come to carry so much power, even those comprising images rather than formal signatures? For instance, talk about the Hopi Indian petition in the exhibit.

JOHNSONYes. That is a great example of the power of petitions petitioning as a right of ours under the First Amendment. And it's been used -- been well utilized in our history. We have many, many, many petitions in our holdings. And the Hopi petition was sent to the government as a response to the Dawes Act. The Dawes Act allowed or mandated that land to be given in individual allotments to Native Americans.

JOHNSONAnd the Hopis were petitioning that they would be allowed to keep their land communally because not only were they a communal tribe and they farmed communally, but they also were a matrilineal tribe meaning the homes fell under the care and responsibility and ownership, I should say, of the women. So they were fearful that their way of life would slowly go away if the Dawes Act and its mandate proceeded, you know, to allot land individually.

JOHNSONSo the petition they sent in outlines all of this. And what caught my eye about it is that they signed in pictograms. Their signatures are pictures of turtles and eagles and things like that. It's beautiful. And every family in the tribe signed the petition. The whole tribe signed the petition. And the government never formally responded to the petition but a Bureau of Indian Affairs agent did recommend that they acknowledge the petition and allow the Hopi to continue their way of life, because that would be in their best interest.

NNAMDISo the Hopis' land was never formally allotted. But from the exhibit -- reading form the exhibit page it says, petitioning the Washington chiefs, during the last two years strangers have looked over our land with spyglasses and made marks upon it, and we know but little of what this means. Fascinating language.

JOHNSONYes. Yeah, the language in the petition, yes.

NNAMDI...in the Hopi Petition. All of this you can find at the exhibit. We're talking with Jennifer Johnson. She is a curator at the National Archives here in Washington, D. C. You can call us at 800-433-8850. Jennifer, please don your headphones because we're about to hear from Tom in Great Falls, Va. Tom, you're on the air. Go ahead, please.

TOMHi. Good afternoon, Kojo. Love the show and hopefully the story will make people realize that sometimes trash can turn into treasure. In 1971, walking around by the White House and I was about maybe eight or nine years old, I'm always picking up trash and, you know, unburied, you know, treasures. And I see this envelope addressed to someone and it said the White House in the upper left-hand corner. So I picked it up and inside is an autographed recipe on White House stationary for Julie Nixon Eisenhower's meatball and tomato sauce recipe.

TOMSo from '71 I've had this thing and it wasn't until last year that I tried to put it online to sell it to get what I call the ERP, the early retirement plan. And it turned out to be not an original signature and worth just pennies. So all these years of hanging onto this priceless object, but I always wondered how...

NNAMDIBut it taught you a lesson, didn't it, Tom, on why people throw stuff away?

TOMWell, they didn't throw it away. I think it must have gotten blown away or the recipe was horrible. Since '71, I've never tried the recipe. But I'm anxious to see if those meatballs really taste as good as the White House would have served to their guests.

NNAMDISorry you couldn't cash in on it, however, because it was not an original signature. But, yes. Jennifer Johnson, care to comment?

JOHNSONYeah, you know, you wouldn't be the first person to hold a piece of paper because of the autograph on it or the signature. In fact, the exhibit itself has several examples of autographs, even people as high as the level of the president collecting them. We have on display, one of my favorite things, which is a dinner program from the Potsdam Conference, as World War II was coming to an end. And on the cover, the signatures are Truman, Churchill and Stalin. And the inside is signed by many of the men and women who attended the dinner that night. But the story is, is that President Truman, when he was at the dinner, passed his own program around to get autographs or to get everyone to sign it.

NNAMDIBecause he immediately recognized the historical significance of it.

JOHNSONYeah. And it was sent home, actually, in a letter to his only child, his daughter Margaret. And he sent it to her.

NNAMDISo even presidents want autographs.

JOHNSONEven presidents.

NNAMDIGot to take a short break. If you have called, stay on the line. When we come back, we'll continue our conversation with Jennifer Johnson. She is a curator at the National Archives here in Washington, D.C. We're inviting your calls at 800-433-8850. What value do you place on a signature, whoever it's from? 800-433-8850. You can send email to kojo@wamu.org. If you'd like to see aspects of the exhibit, you can go to our website, kojoshow.org, and you can test your presidential signature knowledge with a quiz that you can find there. I'm Kojo Nnamdi.

NNAMDIWelcome back. We're talking with Jennifer Johnson, a curator at the National Archives here in Washington, about an exhibit now at the Archives that explores the power and the poignancy of signatures. You can call us at 800-433-8850. Jennifer, the infamous have a place in this exhibit, alongside our founding fathers, former presidents and favorite celebrities. And one of the smallest items is among the most mysterious. What of John Wilkes Booth?

JOHNSONAh, that's a fun one. It's a calling card. So it's very small, maybe two inches by three inches.

NNAMDIBut an ominous calling card.

JOHNSONVery ominous. The only words on it are, "Don't wish to disturb you. Are you at home?" And then he signs, J. Wilkes Booth. And the story is and what we know about it is that he left that at the hotel that Vice President Johnson was staying at, the day that Lincoln was assassinated. And it's shrouded in mystery, because no one is quite sure what he was doing there. There are many theories about it. But it was seized as evidence later on during the trials. So...

NNAMDIBecause in the conspiracy, he was not the one who was supposed to kill the vice president. He was to kill the president.

JOHNSONCorrect.

NNAMDIWhy would he be leaving a card at the vice president?

JOHNSONSome theories center around that he was there because the man who was supposed to have killed Johnson chickened out, and he was there maybe doing recon and hoping to see that his calling card was placed in a room, so he could know where Johnson was in the hotel. Some theories are even as far out as saying maybe Johnson was meeting with John Wilkes Booth and he himself was involved in this high-level conspiracy. So they're all over the map in terms of what that card meant and what John Wilkes Booth's intentions were that day. So I don't know that we'll ever solve the mystery.

NNAMDIConspiracy theories tend to build on one another. And this card will only build on some more. You also have a signature on display from Adolph Hitler.

JOHNSONYes. We have currently on display the final page of his will, which includes his signature. It was seized after the war, of course, and translated by the military. So people will be able to see that and also, because it was translated, they'll be able to read what his will said.

NNAMDIYou started mentioning this before, so I'd like to get back to it again. Off the page, our concept of what a signature is, has evolved, to include someone's style. Whose unique and standout looks -- standout style do you highlight in this exhibit?

JOHNSONSeveral individuals. As far as presidents and first ladies, Franklin Roosevelt. His favorite cigarette holder is on display. A pair of boots that were worn by George Bush, our 41st president. We do have a jacket that was worn by Ike himself. In fact, he had -- the story behind the jacket is that he didn't like the standard-issue military jacket. It was too long, a little bit uncomfortable. So he had this jacket tailored just for him. And it got cut off right about the waist. It became known as the Ike jacket, and it actually became standard issue to the military a couple years later. But the one that's on display is the one that he actually wore. It has his five-star general pin on the shoulder as well, which is pretty special to see.

NNAMDIDid he attempt to get a patent on his special jacket?

JOHNSONYou know, that's a great question. I'm not sure. I'm not sure.

NNAMDIAfter all, he created it. Here is Elena in Olney, Md. Elena, you're on the air. Go ahead, please.

ELENAHi. Thanks for taking my call. You know, I just wanted to bring a little bit of a different perspective. I think it's really interesting, you know, the way that we write our signatures -- you know, for example, so I came from Russia quite awhile ago, and when we had to go through the process of, you know, getting our Social Security cards and the citizenship, you had to sign. Well, when we were signing in Russia, it usually -- it's not your full name, you know, based on what I saw when my mom and, you know, my grandma and my father were signing.

NNAMDIYes.

ELENASo when we came to, you know, the offices, it was a very exciting moment. So, you know, we were getting our cards and everything. And we signed our signatures. And the clerk at the office said, no, no, no. You need to sign your full name so we can read it. You know? And it was quite an experience. And I just always, you know, makes me think how different, you know, the perspectives are, right?

NNAMDIDid you sign your full name any differently in style from the way you signed it in the abbreviated fashion?

ELENAYeah. I mean, even though I switched the letters into English, you know, when I -- I went into high school. I came from Russia from the eighth grade and I went into high school in the United States.

NNAMDIYes.

ELENAI switched them into English, but they were still abbreviated. They were kind of cursive.

NNAMDIYeah.

ELENAYou know, so a little bit hard to read probably. But then when I was signing for an official document, you know, I was almost scared not to make it legible, you know? Because it was very important, so.

NNAMDIYeah, indeed. Elena, thank you very much for your call. Any indications in the exhibit of changing signatures?

JOHNSONOh, sure. Not everything made it into the gallery. But the easiest example is how the presidents' signatures changed over time. We have, of course, records in the libraries in their childhood, so it's fun to see how their signature changed from, you know, a child into their adult years.

NNAMDIWell, many people don't only have signature styles, they have signature moves. What was President Lyndon Johnson's?

JOHNSONMm, yes. Called the Johnson treatment. He certainly used -- one of his political tools was to use his stature and his height to intimidate, sometimes beg and plead I'm sure, sometimes cajole. But either way, he would lean very closely in to whoever he was talking to, maybe inches from their nose.

NNAMDIThis is a man who liked to get up-close and personal.

JOHNSONYes. And there are several photos that document it at the Lyndon B. Johnson Library. So that was, to me, a style that he had. And it was fun showing in photos in the gallery that he was known for it.

NNAMDIHe characterized the invasion of the personal space. President Johnson did.

JOHNSONExactly.

NNAMDIHere is Emma in Washington, D.C. Emma, you're on the air. Go ahead, please.

EMMAWhen I was very young, I went out to San Francisco in '63, where I worked for Kelly Girls and was assigned to a fundraiser. It was a very small group and it was for Goldwater. And Reagan was the speaker. And it was just for small fundraising. And I met one of his sons. And they introduced me to Goldwater, who autographed the program that I had. I was actually working (unintelligible) . And then, later, when I came back to Washington and Reagan was in office, I still had the program. I sent it to the White House to have Reagan autograph it. The only thing is that it never came back. I even tried to reach Helen Thomas to say, was there any way that they might find the program.

NNAMDIShe would ask at a press conference, what did you do with Emma's signature?

EMMANo, no. I thought she might know somebody that would know how to get it back, because it had Goldwater's autograph, and I wanted Reagan's autograph on it. But anyway...

NNAMDIMaybe he did, too. He wanted Goldwater's autograph.

EMMAIt never came back.

NNAMDIOkay.

EMMABut I heard Reagan, and it was a wonderful speech that he gave then. Okay, thank you.

NNAMDIThank you very much for your call. President Reagan might have wanted Goldwater's autograph.

JOHNSONMaybe.

NNAMDIWho knew? Because of the nature of the Archives vast collection, you have some seemingly mundane records in this exhibit that tell fascinating stories. What do we learn about people like Harry Houdini, Babe Ruth and Al Capone, from their World War I draft cards?

JOHNSONWell, those cards themselves are a great resource of information -- things like height and weight and occupation at the time. But World War I, there was a draft. And over 24 million men registered. So we have a vast array of names scattered throughout those 24 million. Things you might be surprised to hear, that Harry Houdini signed his, Harry Handcuff Houdini. He listed his middle name as Handcuff. Even Al Capone, you get to see his signature and that he, I think, was a paperboy at the time.

NNAMDIHe listed his next of kin.

JOHNSONYes.

NNAMDIAs Mother Teresa Capone.

JOHNSONA bit of humor too.

NNAMDIYes. It was ironically funny then but it really sure is now. And George Herman Ruth placed his place of employment as Fenway Park, which was really, well, his place of employment. All of these you can find at the exhibit. You can also learn, in looking at the card, that if a person is of African descent, tear off this corner. So the forms themselves tell stories?

JOHNSONYes. In fact, Marcus Garvey is up there along with those men. And his card, the corner is torn off. I guess it was a way of filing that they would visually be able to see quickly, being that the Army of course wasn't integrated at that point.

NNAMDIAnd of course Marcus Garvey was particularly proud of being of African descent. Sometimes the celebrity and the political collide. A number of celebrities have written to presidents over the years to either express their support for the person in that office or on behalf of others. For example, why and when did Johnny Cash reach out to President Gerald Ford?

JOHNSONWell, Johnny Cash wrote to President Ford two days after he gave his press conference announcing that he was going to give Nixon an unconditional pardon for crimes that he might have committed against the United States. So it was an unpopular press conference. And also, in that same press conference -- although he did not implement any plans at that point -- he announced that there were plans in place to create an amnesty program for Vietnam War draft resisters. So Johnny Cash sent a letter to Ford expressing his support for both his decision on amnesty and pardons. And then he signs it. And the letter is even fun itself, because he has his own letterhead. So you can see Johnny Cash letterhead on display.

NNAMDIOutside of the practical, outside of the legal value of signatures, our popular culture puts a premium on items especially ephemeral -- like menus, photos, letters or playbills -- that have been signed by figures of renown. Many collectors include, well, other celebrities. Did that surprise you at all in putting this collection together?

JOHNSONIt did, especially when I learned -- I mentioned Truman earlier -- but even Jackie Kennedy herself was fond of collecting autographs. It was not uncommon for her to ask for a visiting leader to sign a reading copy of their speech or a dinner seating card. So that proved to be very interesting to read about.

NNAMDIAh, here's a pen. Can I have your autograph, please? You don't see kids carrying around autograph books today, though they're still sought after and prized. What do you think gives them their value? Are they, in a way, the original selfie?

JOHNSONPerhaps so. It is an interesting question. Is it the power of being in that moment? Is it the fact that you can take away a small piece, that signature, of someone? It is something fun to explore and then to see the variety of autographs that are on display, too. For instance, Michael Jackson shows up in the exhibit. He created a patent for one -- for a shoe, so his dancers could do a signature move. It's that lean that they do in his "Smooth Criminal" video, where they lean -- it's a gravity lean, about 45 degrees forward. But he worked with a couple of designers to create a special shoe for his dancers. And we now have his patent and his signature.

NNAMDINo wonder I could never do that lean. I didn't have the right shoe. Here's Bill in Burke, Va. Bill, we're almost out of time. But go ahead, please.

BILLOkay. Kojo, great show. Just two comments. The gentleman earlier said that he didn't make any money off the piece of paper he picked up off the ground. However, my brother-in-law from Falls Church had a baseball signed by Babe Ruth, which was subsequently picked up by a corporation and paid for and sent to the Baseball Hall of Fame. The second article has to do with a check I got from my aunt a long time ago, when I was a young kid. And I thought, boy that signature's really nice. So I held on to the check with the signature. It kind of screwed up my aunt's checking account for a long time. But I still have that check.

NNAMDIWell, try to cash it soon. I'm afraid we're just about out of time. Jennifer Johnson is a curator at the National Archives here in Washington, D.C. You can go to our website, kojoshow.org, and find out more about the exhibit. Thank you so much for joining us.

JOHNSONThank you.

NNAMDIAnd thank you all for listening. I'm Kojo Nnamdi.

On this last episode, we look back on 23 years of joyous, difficult and always informative conversation.

Kojo talks with author Briana Thomas about her book “Black Broadway In Washington D.C.,” and the District’s rich Black history.

Poet, essayist and editor Kevin Young is the second director of the Smithsonian's National Museum of African American History and Culture. He joins Kojo to talk about his vision for the museum and how it can help us make sense of this moment in history.

Ms. Woodruff joins us to talk about her successful career in broadcasting, how the field of journalism has changed over the decades and why she chose to make D.C. home.