Saying Goodbye To The Kojo Nnamdi Show

On this last episode, we look back on 23 years of joyous, difficult and always informative conversation.

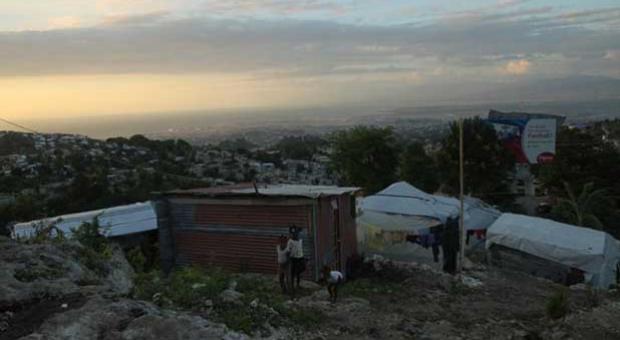

A view of Port-au-Prince, Haiti, at sunset from a hilltop camp in November 2010.

Jonathan Katz was the only full-time American news correspondent working in Haiti at the time of the country’s epic earthquake in 2010. In the aftermath of the disaster, billions of dollars and thousands of nongovernmental organization’s flooded Haiti to aid in the recovery — and Katz soon had plenty of foreign company. Today, many of the most basic promises of that recovery effort remain unfulfilled. We chat with Katz about what went wrong and what’s in store for the country he covered for years.

Introduction

“Why Haiti?” Hillary Rodham Clinton asked in early 2010, speaking on behalf of a bewildered world. The earthquake that leveled Port-au-Prince and much of southern Haiti had defied logic, imagination, even superstition. How did a magnitude 7.0 temblor—a huge release of energy, but not necessarily catastrophic—prove to be the deadliest natural disaster ever recorded in the Western Hemisphere? Why did an earthquake, of all calamities, strike at the heart of a nation already reeling from so many others? And why, three years after so many countries and ordinary people sent money and help, hasn’t Haiti gotten better?

I wrote this book in part to answer those questions. When the earthquake struck, I had been living in Haiti for two and a half years. I had already seen a lifetime’s worth of disasters, both political and natural. Two centuries of turmoil and foreign meddling had left a Haitian state so anemic it couldn’t even count how many citizens it had. Millions were packed in and around the nation’s capital, living in poorly made buildings stacked atop a fault line. People could not rely on police, a fire department, or schools. Even the rat-infested General Hospital charged so much for basic medicine that few Haitians could afford care. Nearly everything—water, gas for generators, hungry relatives from the countryside—was delivered by truck. Each day, big eighteen-wheelers rumbled down the narrow streets, shaking homes as they passed. When the shockwave surged through Port-au-Prince, just fifteen miles from the epicenter, many of us thought at first that it was a gwo machin, a big truck, going by.

I wanted to understand how people could endure not only the catastrophe that befell Haiti on January 12, 2010, but also the hardship and absurdity that followed. The aid response was marked by the best intentions: an international outpouring for Port-au-Prince, Carrefour, Jacmel, Léogâne, and other cities in the disaster zone. The numbers were astounding: The world spent more than $5.2 billion on the emergency relief effort; private donations reached $1.4 billion in the United States alone.1 Thousands of doctors and nurses performed lifesaving surgeries. When it came time to plan for the future, governments pledged about $10 billion more for Haiti’s recovery and reconstruction, promising to build a better, safer, more prosperous Haiti than before. “We need Haiti to succeed,” Hillary Clinton told a donors’ conference, as she answered her own question. “What happens there has repercussions far beyond its borders.”2

But today, Haiti is not better off. It ended its year of earthquakes with three new crises: nearly a million people still homeless; political riots fueled by frustration over the stalled reconstruction; and the worst cholera epidemic in recent history, likely caused by the very UN soldiers sent to Haiti to protect its people (that story, and my investigation, appear later in the book). Those few who were fortunate enough to leave post-quake camps—an estimated 400,000 still lived under tarps as of mid-2012—usually settled in houses no safer than the ones that collapsed in the earthquake. Though by the time you read this book, the ruins of the devastated National Palace might finally have been cleared, rubble, some mixed with human remains, still chokes much of the city. At last count, more than half the reconstruction money that was supposed to be delivered as of 2011 remains an unfulfilled promise. For many of my Haitian friends, some of whom you’ll meet in this book, the legacy of the response has been a sense of betrayal.

I wanted to write this book to understand how a massive humanitarian effort, led by the most powerful nation in the world—my country—could cause so much harm and heartache in another that wanted its help so badly. The United States and Haiti have long had a special relationship, though not an easy one. Founded only decades apart, the first republic in the Western Hemisphere at first refused to recognize the second, then brutally occupied it, and finally spent decades meddling in its affairs. The extreme centralization of people and services in Haiti’s capital, Port-au-Prince, which proved so deadly in the earthquake, was in large part a legacy of U.S. policy and actions.

But Haitians admire the American people, and many dream of coming here one day. Haitian Americans have prospered and play major roles in American life while sustaining millions on the island with money sent back (remittances make up more than a quarter of the Haitian economy).3 Many Americans, meanwhile, are fascinated by a close neighbor whose apparent poverty and dysfunction can be used to affirm our wealth and strength, where good deeds can be performed and theories tested, framed by a culture of Vodou and zombies that entices the imagination. Several officials I talked to for this book spoke of a widely held “romanticism” of the black republic among their colleagues.

One of Hillary Clinton’s first acts as secretary of state was to order a review of U.S. policy toward Haiti. That review was finished on the afternoon of January 12, 2010, barely an hour before the earthquake struck.4 The Americans shifted focus quickly and led the response, providing the largest sums of money and huge numbers of personnel—22,000 U.S. troops alone at the height. In many ways, the response’s legacy, good and bad, is an American legacy. We owe it to ourselves to find out what happened.

It’s worth considering Haiti also because of what its experience means for all of us. We are living in a time of record-setting hurricane seasons, droughts, wildfires, blizzards, earthquake clusters, and disease, many reaching places that long ago thought they had developed their way out of trouble. In 2010, natural disasters cost $123 billion and affected 300 million people.5 Understanding how to deal with these crises in the future means understanding what has been done so far. Rescue workers, officials—and, yes, journalists—still approach crises unprepared to think beyond the hoary, illogical clichés that gird disaster response. For instance, that people will panic, riot, or turn on each other after a disaster; typically, they don’t. Or that in fashioning solutions to disasters, doing something is always better than doing nothing, no matter how poorly thought-out it is; it’s not. And, for anyone who gave money to a major aid group, that they were going to be able to spend your $20 donation.

Excerpted from the book THE BIG TRUCK THAT WENT BY by Jonathan M. Katz. Copyright © 2013 by Jonathan M. Katz and reprinted with permission of Palgrave Macmillan, a division of Macmillan Publishers Ltd.

MR. KOJO NNAMDIFrom WAMU 88.5 at American University in Washington, welcome to "The Kojo Nnamdi Show," connecting your neighborhood with the world. Much of the world knows Haiti is a destination for charity. A little more than three years ago, an earthquake leveled the country which was already the poorest in the Western Hemisphere. Billions of dollars in aid were promised from the outside, and thousands upon thousands of people flooded in to help.

MR. KOJO NNAMDIJonathan Katz knew Haiti then as he knows it now, a place he worked and studied from the inside out as a journalist. He was the only full-time U.S. correspondent working there when the quake struck who literally stepped out of the rumble to report from the ground on one of the worst natural disasters the modern world has seen.

MR. KOJO NNAMDIBut since then, he's turned his focus on reporting on the manmade disaster, the relief effort left in Haiti, and whether even the most well-meaning attempts to help the country get back on its feet have instead contributed to much of the poverty and catastrophe that has defined Haiti for decades. Jonathan Katz joins us in studio. He's a journalist and author of "The Big Truck That Went By: How the World Came to Save Haiti and Left Behind a Disaster." He worked as a correspondent for The Associated Press in Haiti from 2007 to 2011. Jonathan Katz, thank you for joining us.

MR. JONATHAN KATZThanks. It's a pleasure to be here.

NNAMDIYou too can join this conversation. If you have questions or comments, give us a call at 800-433-8850. What do you think are the most important lessons that can be taken out of the massive relief effort launched after the 2010 earthquake in Haiti? 800-433-8850. You can send email to kojo@wamu.org and -- or you can send us a tweet, @kojoshow. Thousands of journalists rushed to Haiti in the wake of that earthquake.

NNAMDIWe actually took this radio broadcast there for a week, some 10 months later. But very few foreign journalists experienced the devastation as it happened. Before we talk about the relief effort, Jonathan, what can you tell us about living through the quake itself? You write that at the time you thought the shakes were just a truck passing by your home in Petionville.

KATZThat is right. There had been such a long time that the government in Haiti had been circumvented and desiccated that basically all services that you got in the capital at that time were delivered by private trucks. If you wanted water, it's delivered on a big truck. If you want fuel for your generator because you weren't getting electricity through the lines, it was delivered on a big truck.

KATZAnd I thought that's what it was, another big truck pulling up, although a bit weird because it seemed to be coming from the opposite side of the house that the water truck would have pulled up on that time of day. And within a couple of seconds, I stood up, and I felt some vibrations moving through the floor. And I, you know, heard the sound of plates banging around in the kitchen, and I realized that this was -- something was happening.

KATZAnd then very quickly all heck broke loose. The house started galloping around like it was stuck in turbulence. And the walls started falling down, and the windows started shooting out. And I was pretty convinced that the entire house was probably going to fall on top of me, but I decided that if I tried running down the stairs and running out of the house that way -- I was on the second floor -- that I probably wouldn't make it in time, that if the house did fall that it would pancake on top of me. And I decided to take my chances on the second floor and ride it down.

KATZAnd fortunately, I didn't have to. The shaking stopped. I later found out from a seismic engineer basically about five seconds before the whole thing would have given way, but I was able to ride it out and then get down under my own power thanks to the help of a -- my friend and driver and translator, fixer, Evens Sanon, who was downstairs at the time.

NNAMDIHad you experienced an earthquake before or do you remember the moment at which it went in your mind from big truck passing by to earthquake?

KATZI had been in a very, very small tremor across the border when I was in the Dominican Republic as the correspondent there. I remember I was actually sitting on my bed then, too. I guess I spend a lot of time sitting on beds.

NNAMDIWriters do that.

KATZYeah, yeah. When the bureau and your apartment are the same place, it's a place you end up spending a lot of time. And I remember just, like, feeling this jolt then. And a couple of things fell off the shelf in my bathroom. And I called the seismic agency at the university there, and they confirmed it was an earthquake. But that was really my only experience with one. But nonetheless, it was fairly clear, fairly quickly.

KATZFor -- I have a lot of friends, and I've talked to, you know, many, many Haitians who were also in Port-au-Prince at the time, and many people didn't have the opportunity to figure out what was going on because everything collapsed around them all at once. I had one friend who'd spent a fair amount of time in the Middle East, for instance. And she was convinced that a bomb had gone off because one second she was sitting at her kitchen table, and the next second, she was under all the rumble.

KATZSo she never had a chance to figure it out. I was very lucky in that the shaking was very violent, but the house was more or less withstanding it around me even though it was falling apart and eventually had to be torn down entirely. And so that gave me a little bit of time to try to get my bearings, and I think it was pretty quick that I realized it. You know, that's the funny thing about an earthquake.

KATZThis one lasted, you know, 35 to 45 seconds, but in my memory and even in experiencing it at the time, it felt like hours. So when I tell you that it was fairly quick, you know, and the way I remember it, it's almost like, well, it took a couple of minutes. And then I realized that all of this was happening. It must have been second one I thought it was a truck. Second two, I realized that it was an earthquake. And then, second four, I was trying to figure out how to survive it.

NNAMDIYeah. That big truck sensation we had a small one here in Washington a couple of years ago while we were broadcasting on the air, and that kind of grinding big truck sensation is what we felt at first, but as you point out, when the building begins to shake, you begin to realize that it's more than likely an earthquake. You mentioned your fixer, Evens, earlier. You were working side by side with him.

NNAMDIHe has family throughout the area. You yourself had people you were close to there. But you also had to report. You had a job to do. What do you remember about how those impulses may have conflicted in your head, the impulse on the one hand to do journalism and the other to kind of drop everything and just help?

KATZRight. It was -- I have to say that in some ways it's more of a conflict in my mind looking back than it was at the time. In terms of trying to check on my friends, I was trying to get a hold of them the same way that I was trying to do my job by finding a cellphone connection or an Internet connection that works so I could communicate what was happening around me.

KATZAnd then I think I was spending equal time trying to call various people that I knew around the city and try to call my parents back in the States and try to access an AP bureau. I was very lucky in that couple of minutes after surviving the quake. When I ran out, I was able to get a hold of a BlackBerry. It was -- I'd run up -- we live next to a hotel, called the Hotel Villa Creole...

NNAMDIWhich is where we stayed when we were there in 2010.

KATZYeah, exactly. And the main building had been damaged, and obviously, a lot of the homes around it had -- including mine, were badly damaged, and a number were destroyed. And my next-door neighbor essentially was killed. But I was able to run up, and I was just asking everybody around, you know, do you have a phone? Do you have a phone? (Foreign language spoken), you know, whatever I could say that would work.

KATZAnd an American was coming out of the building, and he was talking on a BlackBerry connection that was working, and he let me borrow it, and so I was able to make that first call to the AP bureau. And I was basically trying to do that in terms of my personal connection so that the people that I knew and cared about because unless I was able to get a hold of somebody, and they were able to call me and say, look, I'm here. I'm trapped. Please come and help move me.

KATZI wouldn't have necessarily known where to go. I was really focused on doing my job as a reporter, and I really felt then and I think I feel now looking back that that was the most vital role that I could play. I knew that I was a witness. I was by profession paid. I was there to be a witness, and obviously, nobody knew when they send me to Haiti that I would be covering an earthquake. But that's how the news works.

KATZYou never know what's going to come up. And I felt that my job was to go around the city and try to get as much information as I possibly could and relay that in as vivid and accurate and complete away as possible to the outside world so that other people would know what was going on both to bring help and just to try to process what was happening so we could all figure out what the next step would be.

KATZBut I know other people who made different choices, and I talked about some of them in the book. A friend of mine, a photographer, an American named Ben Depp and his wife, Alexis, they decided to do the complete opposite thing. He left his cameras at home. And they grabbed pickaxe and their tools, and they went out and tried to free people from the rubble. Honestly, it hardly occurred to me to try to do that that night.

KATZAmong other things, I have no training in freeing people from rubble. I'm not a fireman. I'm not a paramedic. We're trained in emergency response, you know, the emergency kind of first aid sort, of course, that we take as foreign correspondents to be sure that the first thing that we do is not put ourselves or the people that we're trying to help in more danger if we're trying to do some kind of, you know, a medical or a life-saving intervention.

KATZAnd I had no way to know if going in to a rubble pile and trying to free somebody might bring the whole thing down on top of both of us or maybe if I free them, you know, sometimes, if you move somebody, for instance, who has a neck injury, you can cause a lot more damage. I didn't want to get into that, and I didn't have any real ability to. I felt that the job that I could do was to be a reporter.

KATZBut the one thing that I'll say briefly is that there's a moment that I talk about in the book where Evens and I had gone to the house that he was living, the house of his step-family, the Pierres. And three of them were trapped in the rubble and, for all we knew, were lost. And we tried for a while to see what we could do to get them out, but the entire house -- it was, I think, a two-story house -- it had basically imploded on itself.

KATZThere was nothing we could do to get in there without major machinery or at least a team of guys with sledgehammers which actually who ultimately went in there the next day and freed two of them, thankfully. And as we were leaving, we passed an apartment building, a six-story, that had come down entirely. And I remember there was a young woman standing on a car, and she was looking into the building. And she told me that her entire family was trapped inside.

KATZAnd we were just trying to figure out if there was something we could do to help because you could see and I think a number of them had already passed on, but I remember a pair of feet that was sort of near the edge of part of the rubble, and we were trying to maybe move it to try to get at people. And I was using my camera, a little point and shoot that I was carrying with me to use the flash to illuminate the pile to see if we could see what was going on inside.

KATZAnd it wasn't until later, it wasn't until I was writing the book and going back over those photos that I blew one of them up and, you know, turned up the fill flash function, you know, on Picasa and was able to see that there was actually somebody inside that pile looking back at me. And I took two photos, and I could see from those two photos that he was moving. So he was still alive. And that day when I was looking at those pictures, I was -- it's hard to describe, but I was just emotionally devastated. And again, I don't know...

NNAMDIBecause you never saw him while you were taking the picture.

KATZI never saw him.

NNAMDIYou were just using the flash.

KATZRight. And I don't know what I would have done if I had seen him. I don't know if I would have been able to help at all. But I really feel strongly that I did the best that I could, given my skills. And I fulfilled my role as a journalist, and really in the end I think maybe that's all I could have done.

NNAMDIJonathan Katz is our guest. He is a journalist and author of the book, "The Big Truck That Went By: How the World Came to Save Haiti and Left Behind a Disaster." He worked as a correspondent for the Associated Press in Haiti between 2007 and 2011. If you are interested in joining the conversation, send us an email to kojo@wamu.org. You can go to our website, kojoshow.org, join the conversation there. Or just give us a call, 800-433-8850. What happened when you eventually made it to the American embassy that night?

KATZWell, we got a very warm reception. Well, actually, we did not, but actually, we sort of did because a friend of mine who worked at the embassy saw us pull up on, like, I guess, the close circuit and came out to greet us. He was the first of my friends that I knew for sure had survived. And we embraced, and were very happy to see each other. And then the spokesman for the U.S. Embassy came out. It was about 1:00 in the morning by that point. It had taken all of the day to get there. The earthquake struck just before 5 p.m.

KATZAnd he came out and gave me a very terse interview in which he could share absolutely no details whatsoever. And then he went back in. And I wanted to know if it would be possible for us to get inside. My whole goal had been to get to the embassy and use their communication so I could call in the story, maybe send in some of our photos. I wouldn't have minded a shower at that point -- I was covered with dust -- and, you know, a working bathroom. And they wouldn't let us inside, which was -- I had my...

NNAMDIThis is my embassy, what do you mean?

KATZI had fished my passport out of the rubble, specifically knowing, like, just in case -- I mean, they know me. I'm the AP correspondent. But just, you know, just in case, you know, I run into a guard or something, you know, I made sure I have my passport there. Eventually, after a lot of negotiation over a prolonged period of time, they were willing to let me in, but not Evens. And that wasn't cool, so I...

NNAMDIAnd that was a nonstarter.

KATZYeah. I went back, and we both ended up sleeping in the guard shack that night.

NNAMDIGot to take a short break. If you have called, and a few of you have already, stay on the line. We will get to your calls. If you haven't yet, the number is 800-433-8850. What do you think the rush to help Haiti recover after that 2010 earthquake ultimately revealed about the countries and non-governmental organizations that managed that recovery? Are people guilty of thinking they could fix Haiti from the outside? 800-433-8850, I'm Kojo Nnamdi.

NNAMDIWelcome back. Our guest is Jonathan M. Katz. He is author of the book, "The Big Truck That Went By: How the World Came to Save Haiti and Left Behind a Disaster." He worked as a correspondent for the Associated Press in Haiti from 2007 to 2011. So much of what you write drives home that it's imperative to understand what Haiti was like before the quake to comprehend what happened afterwards. You start with an anecdote about a school that collapsed in Petionville, just outside Port-au-Prince, more than a year before the quake. Why did you find that specific incident so illuminating?

KATZLooking back at our memory and really almost immediately, after the earthquake, the memories of that disaster, the collapse of College La Promesse Evangelique, was so -- it was such a foreshock of what ended up happening. No, there's no evidence that there was a tremor or anything like that. In fact, even at the time, I called the U.S. Geological Survey to see if maybe there have been some report of a small earthquake, and there was never a record of one.

KATZBut just the memory of the collapse of that school and the scenes of people rushing in and neighbors and friends and parents trying to save their children from the rubble and then seeing sort of that same drama play out in which the international responders arrived -- obviously, we're talking about one building, so it's only a couple dozen responders.

KATZThis is a much smaller situation. But USAID and the French government sent in firemen from Virginia and Martinique. And they came in with, you know, their big equipment and a crew from CNN and a lot of hope that they were going to be able to save a lot of people from the rubble. But, really, most of the work on saving people had already been done.

KATZIt had been done by the friends and the family and the neighbors and the people who were there. And there were so many parallels. And the other thing that was just ominous and kind of kept echoing in my mind throughout the disaster and as I would see other schools collapsed all over the city after the earthquake in 2010 was that the president, Rene Preval, had really become fixated, I would say, almost obsessed with the collapse of this school. I mean, it was a terrible disaster.

NNAMDIAnd it was just a poorly constructed school.

KATZWell, that's exactly what it was. And nearly a hundred people died. And at that time, the mayor of Port-au-Prince was warning that 60 percent of buildings in the capital were unstable and needed to be raised. We knew the problems. It was built from shoddy concrete. There were building codes on the books, but there was no agency. There was no means of enforcing them.

KATZAnd the president of the country, President Preval, kept going to the site over and over again and just sort of staring into this abyss and thinking and talking about this problem that there were all these schools and all these buildings around the city that were in danger and that if something were to happen, it would be an unimaginable catastrophe. And a year later, it happened.

NNAMDISomething happened.

KATZYeah.

NNAMDIImmediately, after the quake, an avalanche of people here in the United States and throughout the world rushed to pledge money to help. Some $9 billion were pledged to help Haiti recover. You've said the vast majority of money never even made it inside the country. Where did it go?

KATZOh, it -- very, very seldom, first of all, in general does foreign aid actually go from a wealthy country or a donor nation and actually go to the recipient nation, to the poor country that needs the help. Most of the time, this money is spent by donor governments such as the United States on non-governmental organizations or U.N. agencies or chapters of the International Red Cross Movement that are based in the donor countries themselves.

KATZSo that wasn't a huge surprise because that's basically how aid has been done for decades now. And Haiti actually was one of the prototypes for that. It was one of the places where in the late 1970s and the early 1980s, the people who do aid at the U.S. agency for international development, for instance, we're specifically saying --- they were writing these memos -- you can go back and read them -- about let's go around the government.

KATZLet's try to fund these parallel institutions, at that time, were called PVOs, private voluntary organizations. Now they're called NGOs, non-governmental organizations. And at that time, the reason was that Haiti was ruled by a ruthless and corrupt dictatorship of Jean-Claude Duvalier, Baby Doc. And that was -- the idea was they were going to sort of starve the government and go around it and do things on their own.

KATZBut even once that government was gone in 1986 and there were popularly-elected governments that followed, they kept doing that order of business because it just sort of works for them. You know, you got a big contractor, you know, based in the Beltway or elsewhere at the United States, it's much easier to give them the contract, to give contract to the constituents of a member of Congress than it is to send this money overseas and maybe be less sure what's going to happen to it.

KATZAnd that way of doing business very much continued. And the other things that I would add after that are that when you talk about a donor's conference and the pledges of money and everybody here and in Haiti heard those numbers, those are pledges. They're not necessarily promises kept. Very often, governments, you know, you've got an executive branch or the State Department making a promise that Congress has not yet appropriated money for, and so they have no idea whether or not that money is ever actually going to be delivered,

KATZAnd sometimes the money is sort of, I would argue, almost fictive. Perhaps you have money that's tagged as death relief where you're -- for giving a loan that the country was never going to be able to pay back in the first place, so you're telling them that they're now free to use money that they never had or you're re-pledging money that you've already promised for a prior disaster. For instance, there was a lot of money that was pledged in the wake of the 2008 hurricanes and tropical storms that hit Haiti, four in a month.

KATZThere was a donor's conference after that, obviously a smaller scale. But a lot of money that was pledged for that that hadn't been delivered yet was just sort of re-assigned to the earthquake and then that's included in that $9 billion figure. So when we're talking about the money, sometimes we're not actually being clear about what we're saying.

NNAMDILet's go the phones. We'll start with Bonnie in Silver Spring, Md. Bonnie, you're on the air. Go ahead, please.

BONNIEHi. Thank you. One of the things that gets lost and in the talk about money in Haiti, and there's millions of billions of dollars that I think actually did make it to the country, is that there are thousands of grassroots projects started by Haitians themselves that actually need help in funding. But they can't get to that because all the money goes to the big projects.

BONNIEIt's controlled by the multinationals or celebrities. There's a lot of celebrities that raised a lot of money for their projects there. And it would be really great if there'll be a process by which some of these smaller grassroots projects could get left to get off the ground.

NNAMDIWhat do you day, Jonathan Katz?

KATZI think that is true. I think it goes to a larger issue, which is the development of institutions in general. And some of those are going to come from grassroots or community organizations. And I think that's actually vitally important. It's one thing that's often missed when we talk about Haiti.

KATZThere's often big plans, for instance, the big push for scaling up the garment factories for export to the United States that was promoted especially by the Oxford professor, Paul Collier, in 2009 and then that Bill Clinton was appointed as U.N. special envoy to Haiti in 2009 before the earthquake to promote. But we missed the informal sector. We missed the actually quite vibrant and functioning economy and society that's going on on a community level. And that's true with governance, too.

KATZHaiti has an endless parade of community organizations, block organizations, peasant organizations, that know exactly what their needs are, they have very clear priorities. But they don't have means of access to power and money to make those dreams a reality. The only thing that I would add to that is that ultimately, it is important to scale up the national institutions as well.

KATZWhether we're talking, you know, official municipal and departmental-level institutions and then ultimately a national government, I don't think either of those can be ignored. And going to that, one thing that I would say is, well, there's a lot of stuff that made it to Haiti. So there are a lot of things that money was spent on, you know, tarps and bags of rice and hygiene kits and things like that that did get delivered and did end up in people's hands.

KATZA lot of the money ends up getting, literally, for instance, burnt off in the form of jet fuel or man hours for the American troops who were going down to respond after the earthquake and other things like that, which go into that figure when you're talking about humanitarian relief of the 93 percent of humanitarian relief of the $2.43 billion that was just spent in the donor countries themselves and not actually delivered to the country.

KATZAnd one of the things that's important and is going to be very, very difficult but nonetheless is essential is to find ways to move those through institutions in the country themselves, as I said, whether official governmental institutions or also trying to scale up these neighborhood and grassroots groups.

NNAMDIBonnie, thank you very much for your call. We move on to Christina in Falls Church, Va. Christina, your turn.

CHRISTINAGood morning -- good afternoon, rather. I have worked in government. I have worked with NGOs, so I know that there are certain realities. But at the same time, for everyone that I talked to that went on to Haiti, the big message was how uncoordinated all of the aid effort was. And I was just wondering if the author could kind of comment on that. You know, maybe share some ideas about how it could've been done better.

NNAMDIJonathan Katz writes in "The Big Truck That Went By" about how dysfunctional the Haitian government was at the time. And obviously, that was a big -- that had a big impact on the lack of coordination, Jonathan.

KATZIt absolutely did. Yeah, that lack of coordination issue was huge. And by the way, it was huge before the earthquake as well. One of the things that Bill Clinton, as U.N. special envoy, was sent to Haiti to do was to try to get some kind of coordination from this patchwork of NGOs that's often referred to as the republic of NGOs where all of these different groups, many of which are completely unaccountable or are only accountable to their donors elsewhere, are stepping on each other's toe or concentrating all in one area and leaving other areas unaddressed.

KATZAnd that was a huge problem after the earthquake as well. One of the most vivid examples of that, which I talked about in the book, is the fact that there were so much concentration of the aide effort in Port-au-Prince itself and especially in and around Petionville where a lot of foreigners and both the Haitians lived. That -- the area is actually right next to the epicenter, the towns of Leogane and Carrefour, which is basically somewhere between the town on its own and an excerpt of Port-au-Prince, actually went unattended.

KATZAnd so there were people who are waiting a week for help. You know, I remember standing at a school in Carrefour, which reminded me of that school that had collapsed in 2008, and there were all these people who are trapped in the rubble and there was no sign of anybody nearby who was going to provide any kind of help either in getting them out or giving them medical help. So that coordination issue is huge.

KATZAgain, it's a bit of a broken record statement. But if you look at scenarios where these aid efforts have gone better and have produced more lasting kinds of help -- you look, for instance, at the earthquake and tsunami that struck in Japan in 2011. And one of the major differences there is that the Japanese government is a very strong and capable and well-funded and confident organization that was able to take all of this help that was coming in and say, look, we really appreciate this but we're in charge here. And you need to go there, and you need to go there.

KATZAnd, frankly, sir, we really appreciate that, but it's not needed at all. And the Haitian government was not in any position to do that. And that is in part because it was hit so hard by the earthquake because the earthquake struck the capital and because there was such catastrophic loss of life within what they call in Haiti the cadre level basically, you know, the equivalent of legislative assistance. The people who were making the government go. But it also goes back decades, and it is a product of, frankly, the work of the NGOs in foreign governments in all these years to circumvent them.

NNAMDIYou write that so many people involved in the relief effort talked about a goal to help Haiti build back better. You write that it was really hard to find examples of Haitians even being involved in that process, that, from President Rene Preval on down, Haitians were cut out of the rebuilding of their own country. How and why did that happen?

KATZI think...

NNAMDIOK. So the government can't coordinate necessarily because it is somewhat dysfunctional. But why are Haitians, in large measure, left out of the entire process of coordination?

KATZI think when you're talking about ordinary Haitians, it's because it was just easier for the foreigners who are coming in to operate that way. You had so many people who are coming in after the earthquake with no experience in Haiti whatsoever. And even people who did have experience in Haiti very often lacked the basic language skills to communicate to people.

NNAMDIIt's about the language barrier.

KATZThat's huge. It's huge. I mean...

NNAMDI'Cause you have people coming from separate countries speaking a wide variety of languages into a country in which French is the official language but most people speak Creole.

KATZRight. Exactly. Well, Creole's an official language as well and -- although it wasn't for a long time. But it's absolutely true. I mean, you know, for most foreign governments, at a maximum, they want to make sure that there is somebody on hand who speaks French. But that's not the language that's spoken in the country. You look at the humanitarian cluster meetings, for instance, after the earthquake, most of those are being held, for instance, in the U.N. logistics base behind high walls and concertina wire and blue helmets.

KATZYou know, the U.N. peacekeepers with their weapons, standing in turrets watching you come in. Nobody from the outside was going to be able to just sort of sneak into that. And by the outside, I mean, Haiti. And even if they had been able to get in, they wouldn't have understood what was going on because those meetings were being held in English. That was a huge issue. President Rene Preval didn't do himself any favors after the earthquake.

KATZHe had had a unusual governing style dating back throughout his administration, and in fact, going back into his first term in the 1990s in which he basically would respond to crisis catastrophe or other tumult with silence. He was not a fan of giving big speeches. I think he knew that there was often more to be lost by saying something than not. But he really, I think, and this is widely agreed upon, missed a major opportunity. He didn't address the country in the days or weeks following the earthquake. He really never gave a big post-earthquake address.

KATZAnd I think that the international community saw that. And again, I don't think it took much prodding or justification for them to want to avoid the Haitian government or do things on their own without involving the technocrats who were there on the ground. But nonetheless that gave them even more justification to do so because they saw what they perceived as a complete lack of leadership and they decided that they would fill that vacuum themselves. But it just doesn't really work.

NNAMDICommenting on the same issue is Veronique in Washington, D.C. Veronique, your turn.

VERONIQUEHi. Thank you so much for doing this very important show. I myself am a Haitian diaspora member, and one of the critical frustrations that was articulated and wildly ignored was the lack of use of Haitian diaspora, not only in the assistance but really in the rebuilding of Haiti whether you had people with expertise, whether it was in governance, engineering, medical field, et cetera. And a lot of the ire has been expressed not only toward the government in Haiti and the United States, but also towards NGO. And I'd like to hear what your guest has to say on this.

NNAMDIJonathan.

KATZThe diaspora has a hugely important role to play, and it is becoming a more powerful political force and economic force in recent decades than it was even just a couple of decades ago. So in some ways, this earthquake struck really perhaps at a time when the diaspora is really starting to come into its own. And perhaps in the next few years if, God forbid, there should be another disaster like this or another opportunity for global involvement, you'll see it at a higher level.

KATZThe -- a lot of the principal players -- including President Clinton, the U.N. special envoy Dr. Paul Farmer, his assistant, Hillary Clinton, who was then the secretary of state -- at least paid a lot of lip service and I think did a fair amount of consulting with prominent people in the diaspora. But nonetheless, I think the caller is absolutely right that there was a much larger role that could have been played.

KATZAnd, you know, just at the most basic level, we're talking about language again. It makes the most sense to bring in people who know the culture, know the context, speak the language and are able to, you know, act more than as intermediaries, but actually be making policy decisions themselves. And I think we will see more of that in the years to come, and I think it definitely was lacking after the quake.

NNAMDIThank you very much for your call, Veronique. We're going to take another short break. If you have called, stay on the line. We'll try to get to your calls. You can also shoot us an email to kojo@wamu.org. Were you compelled to contribute money to the relief effort after the 2010 earthquake that devastated Haiti? Why did you give money, and what curiosity did you have afterward for where it went? 800-433-8850. I'm Kojo Nnamdi.

NNAMDIHaiti after the earthquake is what we're talking about with Jonathan Katz. He is a journalist and author of the book "The Big Truck That Went By: How the World Came to Save Haiti and Left Behind a Disaster." Jonathan Katz worked as a correspondent for the Associated Press in Haiti from 2007 to 2011. I want to get back to the phones with two issues I'd like to discuss, the first of which has to do with the cholera epidemic.

NNAMDIWe arrived in Haiti in November 2010, just a few weeks after you started reporting on the outbreak of cholera. You were the reporter who broke the story that connected the cholera epidemic to U.N. workers from Nepal who were in a rural part of the country. Thousands of Haitians have died from that disease since 2010. You say that, to this day, the U.N. has refused to consider its own accountability in how it started the epidemic and that it has therefore missed an opportunity to show that it takes the lives and welfare of Haitians as seriously as its own.

KATZThat's absolutely so. And beyond that, the United Nations, as the world's pre-eminent humanitarian organization and a pre-eminent proponent of the rule of law, has really missed an opportunity to set the kind of example that they say they're trying to do with this peacekeeping mission. The peacekeepers have been in place since 2004, actually, so they were not there strictly responding to the earthquake.

KATZBut it was a contingent of Nepalese peacekeepers, soldiers from Nepal who had rotated in on a regular scheduled rotation in October of 2010. And all scientific evidence at this point really points to them being responsible for the epidemic. Most recently, the United Nations has refused a lawsuit, essentially, asking for compensation on behalf of the victims of the cholera epidemic.

KATZNot only are they saying that they don't want to pay any compensation, not only are they saying that they don't want to issue an apology, but they don't even want to open the provision under a status of forces agreement to even consider the claim. In other words, they're not even giving people their day in court.

NNAMDIWhere do you see this dispute about cholera headed, and what do you feel will be the long-term consequences for the U.N. because of it?

KATZI think because of the way that it has been managed so far, the consequences are actually going to be very bad. And I think that actually they are going to be much worse than they otherwise would have had to be. Nobody -- or, I should say, very few people are alleging that the United Nations brought this disease intentionally. I mean, by all appearances, it looks like it was the product of just absolute negligence.

KATZThey had very bad sanitation at their bases all over the country, frankly probably all over the world. But this one in particular was leaking sewage like a sieve, and the United Nations knew that. They did nothing about it. And then even after all this evidence started mounting, they refused to, as I said, even consider their own responsibility.

KATZIf they had stepped in immediately and said, look, we think we may be responsible for this, we are very sorry, we are doing everything that we possibly can to stem the flow of this disease, we are going to work with you, I really think that, for the most part, Haitians would have understood. There obviously would have been a lot of rightly furious people that the negligence had happened in the first place. But people are understanding. And they can be forgiving, and they can work together with people who want to work with them.

KATZBut the fact that the United Nations, up to the level of the secretary general, have continued to obfuscate and to dissemble and to try to change the topic whenever this comes up -- even though at all levels, including within the United States government, I mean, really everybody knows that they are responsible at this point -- they really are -- they're really creating a situation in which they are destroying their own credibility and probably the effectiveness of the peacekeeping mission.

NNAMDIThe other issue, before we go back to the phones, Bill Clinton was back in Haiti earlier this month. He's been the U.N. special envoy to Haiti. So much of the coverage of the disaster response was celebrity-driven, whether it focused on Bill Clinton or on Wyclef Jean or on Sean Penn. About a year ago, we spoke to the journalist Katherine Boo.

NNAMDIShe had just written a book about life in one of Mumbai's slums. She was very critical about the degree to which people in countries like the United States fetishize poverty in places like India. Do you feel the same can be said for a country like Haiti? You seem fascinated by the fact that there have always been people convinced that they can fix Haiti.

KATZOh, absolutely. People go to Haiti. It's a sort of a combination sometimes of a sandbox or a Petri dish. You can come in from the outside. And if you have even a modicum of power, which I do as, you know, a -- they call it blanc. It comes from the French word for white, but it essentially means foreigner. You know, I come in with my relative wealth and power, and I really can sort of go where I want and more or less do what I want.

KATZWhen you add on to that the incredible power that we give to celebrities in this country -- and we really do give an almost unfathomable degree of credibility and responsibility to people whose chief qualification is essentially being able to perhaps act or look good on a television and -- or a movie screen.

KATZAnd when you bring that disparity of power to Haiti, it really becomes incredible. And so you have a situation with, for instance, Sean Penn, who came to Haiti. He had founded an NGO, and they were coming to try to help with anything they could in the days after the earthquake. And within very short order, he became one of the most important people in the entire humanitarian effort.

KATZHe essentially became the mayor of a town of 40- to 60,000 people and helping to make decisions that have -- are going to have generational impacts on their lives on no authority and no experience other than the fact that he had access to money and power as a celebrity. I just want to say real fast that I don't think that, for instance, everything that Sean Penn did was bad. I think, in fact, in many ways, his organization -- it's called J/P HRO -- has actually done a lot of good work and, in some ways, has been a model for a lot of other NGOs.

KATZAnd when he speaks now, I think he's very well informed, and he got up to speed very quickly. And in many ways he sounds as confident as, you know, perhaps most humanitarian directors. But at the beginning especially, he was making a lot of mistakes. And I think that we just need to sort of ask ourselves as a society why do we give this kind of power and responsibility to people for whom being in a movie is their main qualification?

NNAMDIHere's Constance in Arlington, Va. Constance, you're on the air. Go ahead, please.

CONSTANCEThank you. I've been to Haiti several times with my church. We have choir program in Medor, Haiti. I've read kind of prodigiously on Haiti. And one of the questions in the back of my mind is, you know, I've noticed that Haiti keeps being bashed for its corruption, for its terrible leaders, so on and so forth. My question is what is the international community's responsibility, including the United States -- keeping in mind France's history in Haiti, what is our responsibility in terms of keeping the Haitians unable to coalesce and support them in their democracy?

NNAMDIWell, Constance, we don't have a lot of time, so I'm going to just ask Jonathan to talk about France and the United States.

KATZWell, I think everybody in the Western community has a long history in Haiti. The United States does, too, of course. The United States occupied Haiti from 1915 to 1934. It was a fairly brutal occupation mainly aimed at improving the odds of doing business for American companies down there and that still has a legacy today. Corruption is often used as an excuse to do what we want to do anyway, which is sort of keep the money ourselves and avoid transferring money and power to other people.

KATZThat is not to say that corruption is not a real problem. It is a serious problem, and really, frankly, it infects both the Haitian government and often times the NGOs who are working there unaccountably. And even though it is a -- it is very broad designation that can include things, you know, as desperate as, you know, a cop demanding a bribe on the street or, you know, somebody paying a little extra for a contract, it doesn't necessarily always go to the level of the government, you know, stealing all the money that comes in and using it to, you know, buy cars.

KATZThere's no clear evidence that that kind of thing was happening. And really, frankly, one of the best ways to fight corruption that's been found all over the world is to actually move money through the state institutions, do so responsibly and do so wisely, but enhance their ability to police themselves for corruption. And, you know, for instance, pay policemen salaries that are decent enough to feed their family so they don't need to be out on the streets collecting bribes. We all have a role to play, and we just have to work together.

NNAMDIConstance, thank you very much for your call. We move on now to Laura in Washington, D.C. Laura, you're on the air. Go ahead, please.

LAURAHi, Kojo. Thanks for taking my call, really interesting show. I just want to maybe end on a hopeful note. I work for an organization called Fonkoze. It's the largest microfinance institution in Haiti. It serves all the poor and all the poor women in the rural areas. And we're actually founded by Haitians who've been around about 20 years, and we have over 800 staff of whom I'm one of just a handful of non-Haitians that work in a small Washington office.

LAURASo we were -- we kept our branches open -- our branch open after the earthquake. We help move tens of millions of dollars in remittances during that time. And that we're just really focused on all of the good things about Haiti and trying to just have Haitians helping Haitians.

NNAMDIThank you very much for your call, Laura. It certainly seems like her organization is doing the kind of work that a lot of people are advocating, Jonathan Katz. But before you respond to that or even as you respond to that, can you also take a look at the big picture. Is Haiti's economy fundamentally different, for the better in any way since this earthquake hit?

KATZNot so far. And one of the problems is that the way that most Haitians experience their economy is what we call from the outside an informal economy. But I do have to say that Fonkoze does play a role in that because when you're doing microcredit, you're talking about lending money to people who are essentially participating in that low-level, informal economy. You know, they're selling a couple of things by the side of the street.

KATZThey're operating on very small margins with what you'll consider to be miniscule amounts of money, often pocket change. And while Fonkoze has done very good work, you know, and they are a very well-established organization that takes money from USAID among others, there has been a problem in scaling this up and making this really the prevailing attitude.

KATZYou know, whenever you hear somebody say, for instance, that Haiti suffers from 40 or 50 or 60 or 70 percent unemployment or whatever figure they want to pull out, that should automatically give you pause because as soon as you go to Haiti -- and you can say this as well, you were there -- the first thing you see is that everybody seems to be working.

KATZI mean, there's such a flurry of activity. If you saw activity like that on the streets of Washington, it would be front-page news on The Post. People are just working like crazy everywhere they can. It's just not necessarily in what -- from the outside we consider to be a job. And what people really are looking for is they're looking for improved incomes. They're looking for increased security. They're looking...

NNAMDIThey're selling. They're washing cars. They're cleaning up stuff.

KATZAbsolutely. And what they -- and what people need is a guaranty of some kind that they're going to be able to keep earning money even if they're injured, even if somebody in their family get sick, or they have a divorce, or there are some economic event in their lives that they're going to be able to get through it, and then in the meantime, that they're actually going to be earning enough from their activity, from as hard as they're working to be able to live. And, well, I think that microcredit has a role to play in that.

KATZThat really needs to be the priority, and it needs to be the overall focus of the effort instead of what the focus has been perhaps, which is on these more traditional to us, low-paying factory jobs that are primarily focused for export to the United States that don't create sustainable incomes and don't create a long-term possibility for people to actually be earning enough to help their families. And, you know, that's -- that is a disparity in a conversation that needs to be had. And, again, one way to fix that is by brushing up on our language skills, spending a little more time and going down and listening.

NNAMDILaura, thank you for your call. We got this email from Michael in Foggy Bottom: "I was donating money to Yele Haiti, but it seems to have disappeared. Yele.org still exists and is asking for donations, but I don't know who is behind it now. And if they are reputable, can you ask Jonathan if he knows anything about them?"

KATZTo the best of knowledge, Yele has shut down. I'm -- I'd actually -- I'm actually somewhat surprised to hear that they would still have a website up there that'll be asking for donations. I would definitely be skeptical about that at best. Yeah, there were a lot of problems found with Yele. That was Wyclef Jean's organization.

NNAMDIAnd I think when he was on this broadcast last year, he indicated that they'd shut down.

KATZYeah. And there were a lot of problems found. I mean, among other things, donations were being used to pay Wyclef for performing to ostensibly raise money for the organization but at a high -- far higher rate than the market seemed to be normally demanding for one of Mr. Jean's performances. Yeah. You know, Yele seems to be a very sad story and highly problematic. I'd be very skeptical if anybody claimed to be Yele, comes around asking for cash.

NNAMDIIn the one minute or less that we have left, what would you say are the most important things that Haiti and Haiti's government need at this point?

KATZThe important thing is to find ways for the work that is being done in Haiti to be accountable to the Haitian people. Eventually, that role is going to have to be fulfilled by the government. It's not going to be something that can happen tomorrow, but it's a direction that we need to start moving in. And I think that there's a wide appreciation of this even, you know, at high levels within the United States government.

KATZIt's not necessarily true, though, that everybody in Congress is convinced of it yet, and that's probably one of the major obstacles to doing so. But ultimately, this needs to be about the people in Haiti, and it needs to be that the priority is to make the lives of the greatest number of -- and greatest proportion of the Haitian population better as quickly as possible. And I think that the optimism here really is that if we change the way that we're operating, that will be possible in the future, but it requires a change. It requires hard decisions that have to be made.

NNAMDIJonathan Katz is a journalist and author of the book "The Big Truck That Went By: How the World Came to Save Haiti and Left Behind a Disaster." He worked as a correspondent for the Associated Press in Haiti from 2007 to 2011. Jonathan Katz, thank you so much for joining us.

KATZThank you.

NNAMDIAnd thank you all for listening. I'm Kojo Nnamdi.

On this last episode, we look back on 23 years of joyous, difficult and always informative conversation.

Kojo talks with author Briana Thomas about her book “Black Broadway In Washington D.C.,” and the District’s rich Black history.

Poet, essayist and editor Kevin Young is the second director of the Smithsonian's National Museum of African American History and Culture. He joins Kojo to talk about his vision for the museum and how it can help us make sense of this moment in history.

Ms. Woodruff joins us to talk about her successful career in broadcasting, how the field of journalism has changed over the decades and why she chose to make D.C. home.