Saying Goodbye To The Kojo Nnamdi Show

On this last episode, we look back on 23 years of joyous, difficult and always informative conversation.

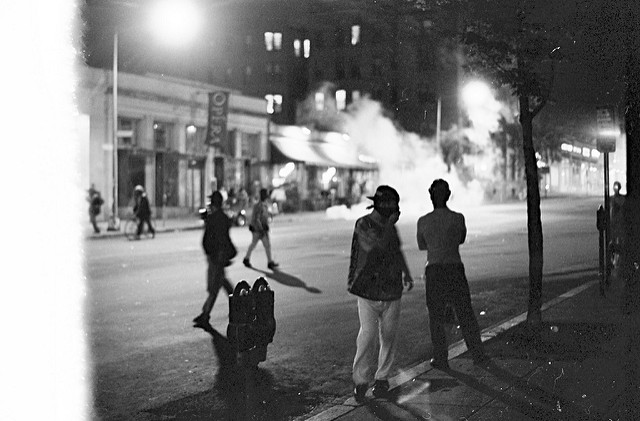

Mt. Pleasant erupted in riots in 1991 after police shot a Salvadoran man in the chest at a Cinco de Mayo celebration.

It’s a moment that defined the Washington region’s Latino community for a generation. Riots consumed D.C.’s Mt. Pleasant neighborhood for three days in 1991 – unrest that erupted after a police officer shot a Salvadoran man. We look at the legacy of the riots on the city and its Hispanic community.

Flickr user secorlew documented scenes from the Mt. Pleasant riots with these photographs taken on May 6, 1991. Some rights reserved:

MR. KOJO NNAMDIOn May 5, 1991, just days after the Rodney King beating sparked chaos that consumed Los Angeles, a rookie D.C. cop shot an inebriated Salvadoran man in Washington's Mt. Pleasant neighborhood, a melting pot of black, white and Hispanic residents just a stone's throw from the White House. The unrest that ensued shaped the Washington region and its Latino community for a generation -- three days of teargas, overturned police cars, hurled rocks and bottles.

MR. KOJO NNAMDIFrom the ashes of the riots arose a Latino civil rights task force, a bilingual police unit and several Latino-oriented social service agencies. And the city's Latino community has grown only larger since then. But that growth and reconciliation has yet to manifest itself in political power for many of the Latinos who live inside and outside of the District. Joining us to have a conversation about the Mt. Pleasant riots, what happened then and since, is Sharon Pratt, who was mayor of the District of Columbia during that time, from 1991 to 1995. She joins us in the studio. Sharon Pratt, good to see you again.

MS. SHARON PRATTAlways a pleasure, Kojo.

NNAMDIAlso with us is Beatriz or BB Otero, currently the deputy mayor for health and human services in the District. She is the founder of CentroNia, a child and family services organization that has been serving D.C. since 1986. BB, always a pleasure.

MS. BEATRIZ "BB" OTEROThank you for having me.

NNAMDIAlso with us is Pedro Aviles. He is now a consultant in Washington. He was the executive director of the Latino rights task force that was set up by the city in the wake of the riots that consumed the Mt. Pleasant neighborhood in 1991. Pedro, good to see you again.

MR. PEDRO AVILESGood to see you again, too, Kojo.

NNAMDIIf you have memories of that occasion and would like to comment on that or what's happened since, you can call us at 800-433-8850. You can also go to our website at kojoshow.org. There, you will find a piece by Emily Friedman that aired on "Metro Connection" last week. It features an interview with D.C. Police Chief Cathy Lanier, who was on the scene as a patrol officer when the riots took place back in 1991. That is kojoshow.org. You can send us a tweet, @kojoshow, or email to kojo@wamu.org.

NNAMDIThe Washington area still wears a lot of scars from the 1968 riots, which erupted after the assassination of Martin Luther King. But 20 years ago, in the melting pot neighborhood of Mt. Pleasant in Northwest, D.C., a different kind of tension in the city's Hispanic community exploded into three days of violent unrest. Sharon Pratt, where, in your understanding, did that tension come from? It seems like, before, we were almost unaware of it.

PRATTWell, I wasn't unaware of it. I mean, I came into office recognizing that the city had to take great strides to move beyond a sense of itself as being basically a sleepy southern town as against a major cosmopolitan city with an enormous influx of new players in the town, and there were growing tensions. And the city was struggling to coexist with the diversity that was now going to be the defining characteristic of Washington, D.C.

NNAMDIPedro Aviles, the source of the tension?

AVILESWell, I think that it was pretty much a police community relations tension. For many years, Latino leaders had warned about the simmering tensions, and I think that the shooting of Daniel Gomez exemplifies the tension that existed between the police and the Latino community. I happened to have a little experience myself, police brutality because...

NNAMDIA few years before that.

AVILESYeah. In 1983 was when I was severely beaten by a member of the D.C. Police Department. And I was just one of them. So I think that when that sad event happened on Mt. Pleasant Street on May 5, it was just the straw that broke the camel's back.

NNAMDIBB Otero, can you walk us back to where you were on May 5, 1991 and what you experienced when the rioting broke out?

OTEROI live very close to where the riots broke out. And I remember many of us who were providing social services in that community and who were, as Sharon says, as a Latino community, struggling to make sure that we were making services available to folks in the neighborhood without a lot of support from the local government at that moment. I think Sharon's absolutely right when she says that we were all in -- from, what, '86 on, sort of hit with a very large migration, immigration into Washington, D.C.

OTEROBut I think one of the first recollections I have of that day is a group of probably about 30 of us making our way up to Mt. Pleasant and standing across on the corner of Mt. Pleasant and Irving Street and almost being a dividing line between the police and the young people who were on Mt. Pleasant to try to begin to mediate some of the conflict that we saw, and we stood there for several hours, where we simply tried to hold back both. And I think there were easily 30 of us from the community that took that stance and then began to organize and meet with local government and those kinds of steps. But it was a very, very scary moment.

NNAMDISharon Pratt, at that time, you had been in office for all of maybe four months at the most. How did that affect your agenda and your plans for the city?

PRATTWell, I came in to office recognizing, again, that we had to make strides and that we needed to have a greater diversity in the cabinet because the government is not gonna be responsive if you don't have a reflection of the community within the government. And we'd made some significant appointments with people like Maria Barreiro and Fe Morales Marks (sp?) and others, including Carmen Ramirez, but whatever I intended to do was upended with this.

PRATTAnd the tragedy that it -- first, we wanted to make certain it was no greater tragedy than what was already unfolding. We did not want to exacerbate the tensions that already existed. We wanted, if possible, to clamp it down in a way that allowed the city to learn from this experience and grow from this experience.

NNAMDIWe came across some archived tape of the riots that were shot by NBC 4 in 1991. Here's what it sounded like on the ground in front of Church's Chicken -- you remember that -- when people started shattering the windows and looting the restaurant?

NNAMDIPedro, BB, you can hear a man trying to calm the crowd by telling them, this is your neighborhood. Did you feel that way? What kind of ownership, sense of ownership of the neighborhood did you feel your community had at that point in the city's history?

AVILESI think that the -- that there was a sense of ownership of the neighborhood in the city, but that went out the window after the shooting of Daniel Gomez because of the accumulated frustration, the sense of alienation that was being experienced by members of the community had reached a limit. And I think that, tragically, what we just heard is what ended up happening. So any sense of ownership of the community at that moment just disappeared, and it was more, I want to assert my right, my existence. I am not -- I don't wanna be invisible anymore. And I think that was kind of the expression that…

NNAMDIBB?

OTEROI think the -- what we have to remember is some of what was happening already throughout the '80s, which Pedro alludes to, sort of the bubbling up of frustration, is that you had a very large Latino community living in Adams Morgan, and Adams Morgan was gentrified in the '80s. A lot of the buildings, all of Calvert Street that had been rooming houses was -- were already beginning to turn over. Buildings were turning over into condominiums, and people being pushed into a different neighborhood, mostly Columbia Heights, in -- and the resistance, obviously, in Columbia Heights, which was a neighborhood that had not been -- that no one had paid attention to since the '68 riots.

OTEROAnd so, you had some of the tensions of a new community coming into already a community that lacked a lot of resources. So the black-white issues, the black-Latino issues that were beginning to emerge mostly because you've had communities that had very -- two communities that had very few resources.

NNAMDIMayor Pratt, I'm thinking that the role that we play, the media, on the very first night, we went out there and we publicized it highly. And one got a sense that after that, there were people who came. Did you get an impression that after that first night, there were a lot of people who were coming from outside of the neighborhood?

PRATTYes, I do. And it escalated rapidly, especially once it got the media attention. Again, some -- a lot of that was driven by genuine feelings of frustration, but certainly, when one realize you have a platform, then inevitably, you're going to start getting more and more attention and more and more participants.

NNAMDIPedro, they used to call them outside agitators, in the old days, a lot of people coming in to the community.

AVILESYeah. I think that there was an element of performance going on here, because I remember that right after the Monday morning when the police department called us to a meeting at the Reeves Building, immediately, we started thinking, what are we gonna do when the young people get out of schools, so we immediately started -- OK, you know, a lot (word?) new centers is going to do this, Sacred Heart is gonna do the other, but it didn't work because of the vans with the (sounds like) microwave bands were already parking up in the street. And some of the young people, when they saw the cameras, they began to act, to perform, to show in front of the camera.

AVILESSo, to a certain degree, that contributed to the looting and the violence. And people were watching it some place, so they decided to say, let's go. There's some action there. And they were not people who were frustrated, I guess. They were people who just wanted to take -- be part of the action, because the TV was bringing it to our homes, living rooms. They wanted to be a part of it. So that's, sort of, like my recollection of the role that the media played in these three days.

NNAMDIOn to the telephones. Here is James in Mt. Pleasant. James, you're on the air. Go ahead, please.

JAMESYeah. Hi, Kojo. I was living in Adams Morgan on Ontario Road, just kind of in from the Safeway on Columbia. And I remember that night I had friends in from out of town, and I'm making them dinner. And my mother in Minneapolis called to say, honey, Dan Rather says there are riots in your neighborhood. And I remember thinking, Mom, don't you think I would know if there were riots in my neighborhood? (laugh) And I hung up the phone and said, Mom, I'll go check, but I think we're OK.

JAMESAnd then we started to smell the tear gas coming in the backdoor, where the kitchen was. And people who are visiting for this Amnesty International conference -- and I was having them sleep on the floor -- they got nervous. And they were from Texas and from Missouri. And they left. And I remember, getting them out of the neighborhood by going down towards Florida. And then I went back. And it's just -- I remember that night was a really intense and powerful, but what is interesting was that there was -- what was really tragic with the next night, the second night, as both Mayor Pratt and you've said, it turned into something very different.

JAMESIt was -- I don't -- I recall it being -- it went from a, kind of, a crisis and a political and this is not right message to looting. And on the corner of Champlain and Euclid where the great neighborhood bike store is, I went out that night and I watched the guys tear off the downspout of the gutter off of a building, and they were gonna use that to smash windows to loot. Now, these people -- they're not from this neighborhood. They don't know where they are, and it became a looting exercise.

JAMESAnd I'm sorry, but the police -- I remember the police zipping up and down Columbia Road. No police were out of their cars, but they were zipping around with flashing, and everybody would hide from it and they go back out. But it became, like, I think, (unintelligible)

NNAMDIAs Pedro pointed out, it became more of a performance by the time of the second evening. Did you ever call your mom to apologize for being wrong?

JAMESWell, I did, because she was right. And I just -- I said, don't worry about me, mom. I'm OK in D.C., but -- or maybe I wasn't, but...

NNAMDIYou're OK.

JAMES...it was not the best time. And now that I live in Adams -- I live in Mt. Pleasant right now in Irving, just below Mt. Pleasant Street. And I got to say it's still a multicultural diverse neighborhood. And it's a great place to live. And it's unfortunate we still refer to this as Mt. Pleasant riot, because it was Mt. Pleasant, Adams Morgan, it was...

NNAMDIYou're absolutely right.

JAMES...it was a mess.

NNAMDIThank you very much for your call and for that memory, James. For you, Sharon Pratt, in 1991, the Washington region was the destination for a steady flow of Salvadoran immigrants who were escaping from the Civil War in their home country. What was your strategy for confronting that challenge of all of these new people coming to the District?

PRATTWell, we did need a lot more hands-on services that were customized to meet this new population. We needed to have -- we needed to beef up and provide resources to community-based organizations that had -- well, better able to respond to the needs of this new population. We also had to have a lot of conversation with the existing residents and the new residents about how we can, as to quote Rodney King, "how we can all get along."

PRATTIt was a challenge. There was so much pushback in all quadrants. I mean, the Afghan-American community, the white community, the Latino community, so suspicious and distrustful of each other. We have come light years from there. So we were -- we had to have boots on the ground on a number of fronts.

NNAMDIYou visited the scene. You imposed a curfew. It's my understanding that at one point during your time on the scene, you actually had to retreat to your car to escape from the teargas.

PRATTYou know, that's what I've been told. I don't remember it as vividly as some, but I don't doubt it. It did escalate very dramatically. And, again, we were trying to contain it, but eventually I recognized we had to have a curfew.

NNAMDIWhat were the conversations you were having with police Chief Ike Fulwood about that time? What were you talking about how to deal with it?

PRATTWell, the main thing is -- and he was of the same thinking that we had to be firm, but we did not want to cause or contribute to this escalating.

NNAMDIGo ahead.

PRATTWe did not want to create a permanent tear. We wanted to do all that we could to create a bridge of communication amongst all of the communities.

NNAMDI800-433-8850 is the number to call. We're talking about what happened on May 5 of 1991, Cinco de Mayo, when there was a shooting by a police officer of an inebriated Latino man in the Mt. Pleasant neighborhood that led to riots in that neighborhood and in Columbia Heights. How do you think the Washington region's Latino community has evolved since the riots that erupted in Mt. Pleasant 20 years ago? You can call us at 800-433-8850. BB Otero, at that time, who were you looking to for leadership?

OTEROI think it -- within -- there were various things happening. Obviously, the leadership of a new administration that had just come in and to really build that bridge, as Sharon said, that a group of us were immediately in contact with her administration trying to give them some of the guidance of the knowledge we had of the community in terms of helping resolve this issue and getting some quick wins that could be seen by the community.

OTEROBut, the also -- the other piece also is that it was opportunity for a bit of a leadership shift within the Latino community. This had been a community that had had a group of people in -- who had worked with previous administrations, and you had a very new group coming in through the immigration, as you spoke about. And I think the opportunity for us to bring in new leadership for either a younger generation to step in, in a particular role, and I think we looked to national Latino leaders and their experiences and asked them for their help. We looked within the community.

OTEROAnd I think, acted -- I have to give Jose Gutierrez a lot of credit who had been in previous administrations, who had been part of the city government. A lot of credit -- he and Raul Yzaguirre from the National Council of La Raza...

NNAMDICorrect.

OTERO...were very, very helpful to us. We sat in restaurants until 2:00, 3:00, 4:00 in the morning, trying to craft what would come out of this from the community as a positive. And that's how the Latino Civil Rights Task Force came out. A group of us on the board, and Pedro, initially, I think, chaired the board. And then I subsequently followed him, and he was executive director. But it was also -- we knew it was an opportunity that we could turn in to a very positive for the Latino community and its emerging leadership.

NNAMDIBB Otero mentioned you as the first executive director of the Latino Rights Task Force, Pedro Aviles, what did you see as your responsibility in that task force?

AVILESI saw that my responsibility was primarily to facilitate a participatory process, whereby people who were working in many areas would bring their expertise and knowledge about existing gaps. I had just come back from El Salvador after a two-year hiatus, and Sharon had just been elected. I hadn't even met you yet back then. And I was kind of thrusted into this position of leadership primarily because I spoke English. I was from -- I am from El Salvador. I've known some of the actors -- Jose, Sonia Gutierrez and so forth.

AVILESMy role was primarily to facilitate the process. I remember that I jumped into meetings to facilitate because everybody wanted to speak at once, so I started writing names. I said, you're next, you're next, and so somehow I started that playing facilitator's role. And it was also my role to be a spokesperson, to be -- to articulate, to the best of my knowledge, the underlying causes of the disturbances, and then to engage with the administration to explore possibilities.

AVILESYou know, you might recall that, Sharon, that we didn't come to you with a set of recommendations until five months later because it took us five months for us to put our heads together, you know, be orderly in a process that included as many individuals as possible, and finally, we were able to present to you the Latino blueprint for action. I was actually going through it this past few months as I've been doing interviews, and I was really impressed to see what a great job the people did.

AVILESI mean, I'm not taking credit for it is because everything that's in that document was drafted by different working committees. BB played a key role in education, Maria -- Carmen Ramirez in health and, you know, and so on and so on. So it was pretty much a participatory democratic process of the whole community. I mean, we used to have open meetings in the halls of All Souls Church, and everybody was invited, Latinos or non-Latinos. So that was pretty much my role and -- be a spokesperson and to facilitate a participatory process.

MR. KOJO NNMADIWell, we'll talk about what happened after that after we take this short break and the situation facing Latinos in Washington, D.C. today. Again, you can call us at 800-433-8850 or go to our website kojoshow.org, join the conversation there. Send us a tweet @kojoshow. Or if you've already called, stay on the line, we will get to your call. I'm Kojo Nnamdi.

MR. KOJO NNMADIWelcome back to our conversation about what happened on Cinco de Mayo, May 5, 1991 in the Mt. Pleasant neighborhood that led to riots and subsequent developments since then. We're talking with Sharon Pratt, who was mayor of the District of Columbia from 1991 to 1995. Beatriz or BB Otero is currently the deputy mayor for Health and Human Services in D.C. She's the founder of CentroNia, a child and family services organization that's been serving D.C. since 1986, and Pedro Aviles is now a consultant. He was the executive director of the Latino Rights Taskforce that was set up in the city in the wake of the riots that consumed the Mt. Pleasant and Columbia rights -- Columbia Heights neighborhood in 1991.

MR. KOJO NNMADISharon Pratt, the other thing the city did, in addition to putting together a Latino affairs taskforce, well, among several other things the city did was the creation of a bilingual police unit. How important was that?

MS. SHARON PRATT KELLYOh, I think that was very important. One, it showed respect. It was a gesture to indicate respect that there is a new community, there are different language, and we respect that. So I think that was a meaningful overture beyond the optics or the symbolism of it, I think, it had very substantive impact.

NNMADIIn addition to that, several of the city's social services agencies started to direct their attention more to Latino community during your administration.

KELLYAbsolutely and -- right. And to also reflect it in bilingual, you know, literature and so forth. So it sensitized the government in a way that no matter how determined I was, I think when the communities expresses themselves so clearly and so vocally, it forces people to pay attention.

NNMADIHow have conditions changed, if at all, for new immigrants to our region today, BB Otero?

OTEROWell, I think the regional experience is very different in each community. The -- I think District of Columbia has a mature Latino community, has been here now for, you know, we're going to a second generation. I know that while you're looking at some of the suburban areas where they are, it was very striking for me. My organization, my -- CentroNia, where I was before, opened up some programs in Montgomery and Prince Georges County about four or five years ago, and one of the things that our staff came back and said was we're dealing with the same issues we dealt with in the mid '80s in D.C. with these new families.

OTEROAnd so we saw a lot of the kinds of things that we saw with the recent immigrant population out in the suburban areas, and so they're very different. Interestingly enough, the suburban areas have managed to do better in terms of political representation. And...

NNMADII was about to say that.

OTERO...that is, I think, a phenomenon that we should probably study and figure out...

NNMADIWe've seen Latinos in positions of political authority in Maryland and Virginia, Walter Tejado in -- Walter Tejada in Virginia in Arlington County, Nancy Navarro in Maryland, but as yet, there has been no Latino D.C. city councilmember. How would you explain that lack of political clout in the Latino community in the District as opposed to other parts of the area?

OTEROI maybe totally wrong, but I think one of the things that is really key is the lack of political -- the -- of -- avenues, of political expression in the District of Columbia by the nature of what the District is. And so we really -- we've lost this -- our school board in terms of the role it had played politically. It is now coming back as an elected board. Really, the only place, other than ANC’s is the city council. And so there are little opportunities for the actual formation of political beings within the city outside of the nonprofit sector.

OTEROAnd so when you look at other jurisdictions, and people have been able to move up the political ladder to elected positions, the District has a very limited set of opportunities, and so I think it's a -- it's been a lot harder. You see many of the people in Montgomery County and in Virginia got their start in the District of Columbia and then moved out to the suburbs.

NNMADISounds like an argument for statehood and voting rights in the District of Columbia (laugh) to you Sharon Pratt.

KELLYI'm all for that. I'm absolutely all for that.

NNMADIThere would be an expansion of offices in the District...

KELLYAnd I think it would. I think it would undoubtedly encourage the diversity, full diversity of participation and reflection in the government, and it would energize people politically. So we are limited, and I think it's a very apt assessment (word?)

NNMADIHow about this as a factor, unlike in, say, Texas or California, where the majority of the Hispanic population is Mexican American, the Latino community here in Washington is something of a melting pot. Sure, there's a big percentage of Salvadorans, especially coming in during the 1980s, but there are also Guatemalans, Hondurans, Mexicans, Puerto Ricans, the list goes on. Does this lack of a strong, single national identity create a challenge for organizers, Pedro?

AVILESI don't think so. My experience has been is that nationality has not been a barrier for coming together. I think that the barrier is more -- immigration status. Not too many of the members of the Salvadoran community are U.S. citizens. Some of them don't have permanent residency. At best, they have temporary protected status. So I think that that is a key barrier. I also think that one challenge that we have as a community is to build coalitions across the city so that if and when we field a capable candidate -- Latino or Latina -- to the city council, that we've built those bridges, those relationships that can allow for our candidates to win. I don't think it's an issue of a Latino not having the capacity.

AVILESI think that we need to build those relationships with the African American community, with the gay and lesbian community, with the Anglo community so that if and when we field someone that we have that -- those working relationships. I think that we have many Latinos who have run, but they have, at most, won, what, 10 percent of the vote?

NNAMDIIn the last at-large city council race, Josh Lopez, who's the son of Guatemalan immigrants, was one of the candidates in that race. Of course he didn't succeed. Your take on the lack of political viability outside of the lack of political -- outside of the lack of enough political offices to occupy?

OTEROI think we have spent so much of our energy as a community in making sure that we bolster up the services for our community. There has been -- if there is one place where we have had really significant growth and, in some ways, have translated our political power into sort of the social service and education realm, we have major institutions, major instiutions that are not just major in the Latino community. They're major for the District. You -- whether you talk about the Latin American Youth Center or Carlos Rosario or Mary's Center or CentroNia or Clinica del Pueblo, I mean, you look at these institutions, and they are some of the strongest institutions that the District has as a whole and are providing incredible leadership in that arena.

OTEROAnd I think we've spent a lot of our energy and a lot of our know-how building these institutions within the District of Columbia. I think it's very telling, for example, that there are over nine or 10 charter schools started by members of the Latino community or institutions within the Latino community. That's a very powerful statement, I think, if you think about the growth in terms of the educational piece and the fact that education was one of the major issues that we found as lacking in the report that we did back in 1991.

NNAMDIHere is Jorge in Washington, D.C. Jorge, you're on the air. Go ahead, please.

JORGEThank you, Kojo, for taking my call. I wanna say hello to Pedro and BB. I live in the Mt. Pleasant area. And I recall the forums that you used to hold, Pedro, regarding the ongoing fights at -- over Malcolm X Park between Latinos and African American community. I think that, currently, Latinos are definitely underrepresented in employment in the city government, specifically the Department of Parks and Recreation, Aquatics Division. I myself am experiencing what I wanted to not categorize as racial discrimination.

JORGEBut I feel that that is basically what is happening there, as well as age discrimination. You don't see Latinos being employed as -- in the Aquatics Division or in Parks and Recreation.

NNAMDIWhat do you do about...

JORGEAnd I'd like to get -- pardon me?

NNAMDIGo ahead, please.

JORGEAnd this is in spite of the fact that we have a Latino directing the Department of Parks and Recreation. And I would like to get some contacts within the D.C. Council or other agencies that could possibly address my situation.

NNAMDIBB Otero, to what extent is discrimination a factor in the District of Columbia?

OTEROAgain, as a -- if we look at the District of Columbia as a city where the African American community saw taking major strides unlike any other place in the country, I think it's very difficult when you ask a community that -- themselves are trying to gain levels of power and political voice to then quickly embrace another group of people into that same power. And I think part of what we dealt with in the District of Columbia and have dealt with in the District of Columbia is that the issue of two groups who were in the process of gaining -- you have to remember that, you know, the civil rights movement and the desegregation of the District of Columbia is not that old.

NNAMDIYeah, but there are some, Sharon Pratt, who would argue that we African Americans are in the best position to understand what it means to be locked out and kept out, and therefore are in the best position to craft policies that are more inclusive.

PRATTI quite agree, and Mickey Leland was one who always agreed with that point of view. Unfortunately, as BB has pointed out, the political fault line of Washington has been pretty much along racial lines of black and white. And almost every election, there is some subtle element of that in all -- in the election. And yet in the midst of that, as we still struggle with it here in 2011 -- and I think we struggle with it longer in Washington because we are a subjugated city -- I think that has a psychological impact upon the city.

PRATTIf we were a fully -- a full -- a sovereign community, I don't think we would be able to dismiss it more easily. But within the midst of it is a rich opportunity that the Latino community -- that someone is going to capitalize upon as the new voice, the new face of Washington, someone who can unite us, someone who expresses the diversity, the cosmopolitan nature of the city, the future of the city, the youth of the city. There is a great opportunity waiting to be had. But, unfortunately, this city is so psychologically in grip still in that Southern sleepy town mindset.

NNAMDIWell, finally, Pedro, we asked your brother, Quique. He told our production intern, Anne Hoffman, in an interview recently that the city's Latino community is struggling to get over a sense of victimhood. Here's what he told us.

NNAMDII think we’re stuck in this whole thing of victimhood. Oh, the poor little immigrants, they came here from El Salvador to sell their tamales to make a living. And then they bought a truck, and then from the truck they built a restaurant, and then they bought houses and they became contractors, oh. The American dream, you know, yes, that continues to happen, but it’s a lot more complex and sophisticated than that nowadays. ‘Cause our kids, you know, barely speak Spanish; they are Americans.

NNAMDIAnd, of course, you can tell that Quique is an artist just by the way he delivered that. What would you say?

AVILESWell, I think that Quique is right to a certain degree. That does not mean that the sense of being a victim is not real. Remember that there is a paradigm here and it's a federally originated paradigm, and that is the absence of comprehensive immigration reform. Anyone who is undocumented, who lives in the shadows of society, it's, in my opinion, somewhat of a victim. Now Quique was talking about how leaders or agency directors speak of victimhood.

AVILESThat may be -- could make a case. I think there's progress has been made in general. But there are still people who are struggling, and that is pretty much across the board. Low-income communities. It doesn't matter whether you are black, white or Hispanic. You are sometimes victims of...

NNAMDIIt's a work in progress.

AVILESExactly.

NNAMDIPedro Aviles is now a consultant. He was the executive director of the Latino Rights Task Force. Pedro, good to see you again. Thank you for joining us.

AVILESThank you for having me.

NNAMDIBeatriz or "BB" Otero is currently the deputy mayor for Health and Human Services in the District. She is the founder of CentroNia, a child and family services organization that's been serving the city since 1986. BB, thank you for joining us.

OTEROThank you very much, Kojo.

NNAMDIAnd Sharon Pratt was mayor of the District of Columbia from 1991 to 1995. Mayor Pratt, always a pleasure. Thank you for joining us.

PRATTThank you, Kojo.

NNAMDIAnd thank you all for listening. I'm Kojo Nnamdi.

On this last episode, we look back on 23 years of joyous, difficult and always informative conversation.

Kojo talks with author Briana Thomas about her book “Black Broadway In Washington D.C.,” and the District’s rich Black history.

Poet, essayist and editor Kevin Young is the second director of the Smithsonian's National Museum of African American History and Culture. He joins Kojo to talk about his vision for the museum and how it can help us make sense of this moment in history.

Ms. Woodruff joins us to talk about her successful career in broadcasting, how the field of journalism has changed over the decades and why she chose to make D.C. home.