May 8, 2015

Where Kids Grow Up Determines How Much They’ll Make

School children in Centreville, VA.

It’s a tried and true adage that location matters –especially when it comes to raising a family. But not only are health, safety and education immediate concerns when you settle down, your zip code can influence how much money your kid earns later in life.

According to a new report by Raj Chetty and Nathaniel Hendren of Harvard University, every year of exposure in a county that offers a better environment improves a child’s chances of future financial success.

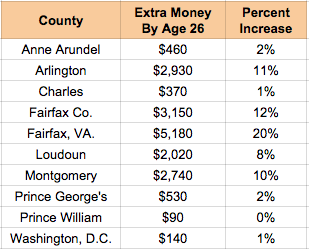

In Washington, D.C. for example, the New York Times reports that Fairfax City is a more ideal place to raise a child than Washington or Prince William County. Using tax records from low-income families who moved locations, the study looked at how much extra money counties in our region cause poor children to make, compared with children in poor families nationwide.

According to the report:

“…the younger you are when you move to Fairfax City, the better you will do on average. Children who move at earlier ages are less likely to become single parents, more likely to go to college and more likely to earn more.”

“Every year a poor child spends in Fairfax City adds about $260 to his or her annual household income at age 26, compared with a childhood spent in the average American county. …the difference adds up to about $5,200, or 20 percent, more in average income as a young adult.”

And what primes a county for strong upward mobility anyway? According to the New York Times, five factors:

- Less segregation by income and race.

- Lower levels of income inequality.

- Better schools.

- Lower rates of violent crime

- A larger share of two-parent households.

These effects are “sharper” for boys than girls and for lower-income children than for rich.

To better understand what this data means for counties in our region, tune in Monday, May 11, to hear Harvard University’s Nathaniel Hendren and the Brookings Institution’s Isabel Sawhill explain its implications.