Saying Goodbye To The Kojo Nnamdi Show

On this last episode, we look back on 23 years of joyous, difficult and always informative conversation.

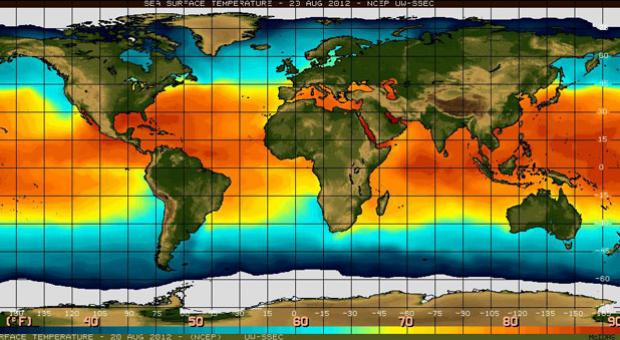

Sea surface temperature in the equatorial Pacific Ocean.

Technology has changed the way we track weather. Apps and websites now give localized information in real time. Farmers and businesses rely on sophisticated modeling to predict conditions weeks and even months in advance. But as the swift and destructive path of this summer’s derecho has proven, our understanding of weather patterns is far from perfect. Tech Tuesday explores how government planners, farmers, energy companies and a range of other businesses use climate and weather data for short and long-range planning.

Droughts, snow accumulation and average temperatures varied widely across the United States compared to previous years. All photos courtesy of NOAA.

Storm surges, elevations and FEMA floodplains for Washington, D.C. Courtesy of the D.C. Department of Environment.

The director of the National Weather Service, National Centers for Environmental Prediction, discusses numerical weather prediction during the February 2010 mid-Atantic snow event known poularly as Snowmageddon:

Listen to the earthquake that caused the Great Honshu, Japan tsunami:

How to detect, understand and predict El Niño and La Niña weather phenomenons:

MR. KOJO NNAMDIFrom WAMU 88.5 at American University in Washington, welcome to "The Kojo Nnamdi Show," connecting your neighborhood with the world. It's Tech Tuesday, and technology has changed the way we track weather. We now have sophisticated modeling systems that can pinpoint local information in real time. Farmers and local businesses can rely on apps and data to predict conditions months in advance.

MR. KOJO NNAMDIBut as the extremes of this summer's weather have proven, we're still vulnerable. Drought, high temperatures and, here in our region, a powerful storm known as a derecho have all taken a deadly toll, and it's clear that our weather and climate prediction are still far from perfect. Tech Tuesday explores how government planners, farmers, energy companies and a range of other businesses use climate and weather data for short- and long-range planning.

MR. KOJO NNAMDIJoining us in studio to have this conversation is Tom Karl. He is director of the National Climatic Data Center in Ashville, N.C. He's in Washington, D.C. today for meetings, and so we're taking advantage of that. Tom Karl, thank you for joining us.

MR. THOMAS KARLThank you so much, Kojo.

NNAMDIAlso in studio with us is Christophe A.G. Tulou, director of the District's Department of the Environment. Christophe, good to see you again.

MR. CHRISTOPHE TULOUThank you, Kojo.

NNAMDIJoining us from studios of KFCR in Denver, Colo. is John Henz, senior meteorologist and technical leader for Dewberry Consultants. John Henz, thank you for joining us.

MR. JOHN HENZWell, thank you. I'm welcome to be here, Kojo.

NNAMDIIf you'd like to join this Tech Tuesday conversation, you can call us at 800-433-8850. You can all send email to kojo@wamu.org, send us a tweet, @kojoshow, using the #TechTuesday, or simply go to our website, kojoshow.org, and join the conversation there. John Henz, climate services is something of a new term, although it apparently describes something that is not new. How would you explain what climate services are?

HENZWell, I think that it's only two words. But I think we could talk, and we probably will end up interacting here over the next half hour or more recognizing how detailed it's become. The climate services can range, as you mentioned yourself, from people at home to Fortune 500 businesses, all the way to agriculture, transportation and people designing infrastructure for delivery of water and electricity to our large population centers and businesses across the country.

HENZThe provision of the services has really expanded not only in the federal government but also in the private sector, and we actually have our university community preparing individuals for interdisciplinary interaction in the climate services.

HENZNow, I think if we look at it, it's looking both at what is going to happen, say, on the operational scale of today through the next week, or, if you're managing a water system, what's going to happen from October through September to the more delicate and considerable interactions that businesses are looking five years ahead at things, such as the exposure to high-impact weather events, such as the derecho that you mentioned, and also drought and oversupply of water in the form of floods, all the way into trying to meet climate change.

NNAMDICould you give us an example of some of the businesses that need this kind of expertise?

HENZWell, right now, the primary one that we find across the country -- actually, there's two of them, and they're energy-related businesses that have the responsibility of delivering electricity, gas to our large metropolitan areas and businesses, and also the supply of water to those of us that every day take it for granted when we just come home. We turn the faucet. We're going to assume that water is going to be there, but certainly, we know that water is one of the big issues that we look at in the future.

HENZIt's also people such as our insurance company when we get our bill every month, and we take a look at our home insurance. Well, they're trying to anticipate what's going on, along with all the growers in the country that are associated with the agricultural industry, trying to make sure that things are OK, and also some things such as this morning's news headlines if you picked up and noticed that the Mississippi River, because the flow is so low in it, has actually closed itself to transportation of goods and services by barge on the Mississippi River.

HENZAnd those are just a small smattering, Kojo, of the number of businesses that utilize the services of climate and climate-related activities.

NNAMDIWhich gives me a specific question for our listeners who might want to join the conversation. Are you in a business or government planning agency that relies on weather data? Give us a call at 800-433-8850. Tom Karl, you direct the National Climatic Data Center, part of the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration. What does the NCDC do?

KARLThat's a great question, Kojo. What we do is we collect all the data that's measured across the world every day from satellites, weather balloons, weather stations, climate-reference stations, ships in the oceans, floats that profile the ocean. All this data is collected, integrated and then distributed to users who try to understand how weather and climate affects their businesses. In addition, we also monitor the national and global climate using all this data and information.

NNAMDIYou can find some samples of what takes place at the NCDC at our website, kojoshow.org, including a drought map of the U.S. Tom, you feel that even an educated public may not really fully appreciate what goes into weather and what goes into seasonal forecasts.

KARLYes. I think it's easy to take for granted the infrastructure that the world, as well as this nation, has put together to actually make the weather forecast or climate prediction that we've all come to know and love. There is a whole suite of international agreements that have been developed by organizations, such as the World Meteorological Organization, Global Climate Observing System, numerous other organizations, to try and agree when we'll collect this data, how the data will be transmitted, how it will be shared, how frequently it'll be transmitted.

KARLIt has to be analyzed in a reasonable timeframe. Standards have to be understood, tremendous amount of agreements, bilateral negotiations, multilateral negotiations to try and make all this technology, from satellites to planes and ships, to work properly.

NNAMDIChristophe, how does the District of Columbia track weather for long- and short-term planning?

TULOUWell, first of all, why would we be interested in doing it?

NNAMDIYes.

TULOUAnd the derecho is a perfect example of our interest in having the best information possible. We don't have our own weather resource, but we do depend on folks like Tom and NCDC for the information that we use then to try to predict what the future will hold for us. Obviously, we listen as attentively as anyone to what the forecasters are telling us over the window of time that they can give us a reasonable forecast, which I will say has gotten tremendously better.

TULOUIt used to be a butt of jokes. Now, typically, the weathermen get it pretty right. But we rely on that information to be able to predict, for example, heat waves, a terrific concern for us in an urban environment where it gets to be 100 degrees for several days as we've witnessed this summer. This is not just an inconvenience. If the power were to go out, as it did on June 29 with the storm that came through on 104-degree day, all of a sudden, we're talking about something that has life-and-death implications, particularly for older people.

TULOUAll we have to do is point to the major heat wave in Europe back in 2003, and close to 15,000 people in France alone perished during the course of that hot weather.

NNAMDIIn case you're just joining us, it's a Tech Tuesday conversation on climate services and changing weather. We just heard from Christophe A.G. Tulou. He is the director of the District of Columbia's Department of the Environment. He is joined in studio by Tom Karl, director of the National Climatic Data Center, NCDC, which is based in Ashville, N.C. And joining us from studios in Denver, Colo. is John Henz, senior meteorologist and technical leader for Dewberry Consultants.

NNAMDIWe're taking your calls at 800-433-8850. You can send email to kojo@wamu.org. Are you in a business or are you involved in a government planning agency and relies on weather data? Tell us about your experience. John Henz, we just heard Christophe say that now we know that weather forecasts, which some used to consider not too seriously, are now more accurate than ever, and technology has seen a revolution in so many areas in the past decade -- digital cameras, phones, data analysis. How about in the area of climate services, John?

HENZWell, I think what's -- what Tom had mentioned is that we have a plethora of information available now on the environment, and organizing it and recognizing how it gives us signals as to what is taking place right now in our atmosphere and the interaction between the oceans and the atmosphere to create these great oceans of air that are moving through the atmosphere and creating the day-to-day weather changes also set up patterns which tend to be persistent.

HENZAnd one of the things I believe, Kojo, that's very interesting as a sort of wakeup call from Mother Nature, if you would, is the great change in the amount of snow, rain, flood, heat and drought that we had from the year 2011 here to 2012. We went from a record number of tornadoes occurring in 2011 to one of the fewest numbers of tornadoes that we have on record. A drought in 2012 during the summer and spring seasons has brought agriculture and other businesses almost to their knees in the middle part of our country.

HENZAnd at the same time last year, in 2011, we were having floods on the Missouri River, the Mississippi River, and I think what it's doing is making us aware that we need to take time to organize this information and utilize it to our advantage to plan both on the short-term change from 2011 to 2012 to what's going to happen over the next five, 10, 15, 20 years.

NNAMDISpeaking of the next 15, 20 years, and John just mentioned some of the extreme weather we've been having, Tom, a lot of people want to know if that extreme weather that we've been seeing can be definitively tied to climate change, record heat waves, drought and the derecho storm that passed through at the end of June here in Washington. But you note that the question you ask is what's important.

KARLYeah. That's a great point, Kojo, because I know that it's shorthand to say, you know, what's going on with extreme weather or climate events. I think we have to remind ourselves there are so many kinds of weather and climate extremes out there. You know, we heard John talk about tornadoes to droughts, the heat waves, the snowstorms, blizzard, hailstorms, hurricanes. It's much more helpful if we can zero in on specific phenomenon, and for some phenomenon, we have more information, better capability to link it to human activities than other types of information.

KARLSo, for example, heat waves, probably one of the areas, extreme precipitation, where it's easier for us to say humans are having an impact on those extreme events, for other events like hurricanes, tornadoes, much more difficult. We have a harder time monitoring those things over multidecadal periods, as well as trying to understand whether humans are having specific impacts today.

NNAMDIAnd, Christophe, we've talked about how these changing weather patterns can have a huge, sometimes deadly impact on people's lives, and so anticipating what's going to happen is crucial. You've talked a little bit about that. But how does the climate change debate fit into that picture?

TULOUIt's much more practical from our perspective in cities, for example, where the majority of the world's population now lives and you know, over 70 percent of folks in the U.S. It's not so -- it's not quite as important for our purposes to lay blame. So we don't necessarily get into a whole lot of the discussion about whether it's human caused or otherwise. But what we do have to face is the reality that these things have always happened.

TULOUThere have been floods in Washington since there was a Washington heat wave since the beginning of time. But what we do know now is that these things are happening more often and with greater ferocity, and we're obliged to plan for that. And that's why we as a team, John, Tom, me and other people in this community, are working together to try to figure out how best to predict those things.

TULOUBut the, you know, it's becoming very clear that what used to be lost in all of the noise of the variability of the system, the climate signal or signature is now a very distinct fingerprint, and it's becoming a handprint and very shortly will be a footprint. And so we have to deal with that in planning for the future. And how do we do that as city? By acknowledging that we're in for a fight, and we need to train like a prized fighter would to be adaptive. And we're not going to be able to avoid all the shots, but we need to be able to figure out how to get back up when we do take one.

NNAMDIAnd, John Henz, the extreme weather we've been seeing and the always heated discussion about climate change obviously has a lot to do with us talking about climate and weather these days. But you say that climate services has been around for a long time.

HENZYeah. Climate services probably have been long -- as long as we've had meteorologists. One of the things that's a little known factor here in the United States, I think, is that we have a very large private meteorological community. That meteorological community not only works for private meteorological firms, but for many big businesses. Many large engineering companies over the last decade especially have recognized the relationship between meteorology, climate and the development of engineering services for cities such as Washington, D.C.

HENZAnd, of course, we rely on organizing and using the information, such as the National Climate Data Center as Tom pointed out, to try and assist in design. But this is not a new thing. We've had meteorologists interacting with the insurance industries, with agriculture in providing long-term outlooks, energy companies, such as coal companies, gas companies, for well over 30 years, and many of those services have been developed.

HENZBut they provide a strategic, competitive edge at times, and you won't hear businesses talking or sharing what they know about climate and climate variability on a natural basis because they use that in their businesses.

NNAMDIIt's the competitive edge, huh?

HENZOh, it really is. In fact, one of the interesting ones was even a pro football team, the Denver Broncos used forecast services that we used a number of years ago, and they won a couple of games one season. They said it made a difference between a winning and a losing season for them simply to know it was going to rain on out or snow out during the first half or second half and change the size of cleats. Now, that's a really small thing.

HENZBut I think when you're looking on a larger scale, especially the impacts on commodity markets and perhaps something more significant, the ability to anticipate the amount of water that we're going to keep in our reservoirs when we're switching from a, let's say, a flood period, when you want to maintain a flood pool for more water that's coming down as opposed to when you go into a drought and you want to hang on to every drop you can in that reservoir and effectively being able to organize this information is very important.

HENZAnd I think over the last 20 to 30 years, the engineering community and the meteorological community have recognized they can share and help and work with other businesses and communities to anticipate these changes. But, boy, we have a lot to learn here, Kojo.

NNAMDIGo to take short break. But you can still call us. Where do you get your weather information? 800-433-8850. Do you think it's gotten more accurate? You can also send us email to kojo@wamu.org. Do you think there's a link between the extreme weather we're seeing and climate change? You can also go to our website, kojoshow.org, and join the conversation there, or send us a tweet, @kojoshow, using the #TechTuesday. I'm Kojo Nnamdi.

NNAMDIWelcome back. It's a Tech Tuesday conversation. We're discussing changing weather conditions and climate services with Christophe A.G. Tulou. He is the director of the District of Columbia's Department of the Environment. John Henz is senior meteorologist and technical leader for Dewberry Consultants, and Tom Karl is director of the National Climatic Data Center, NCDC, in Nashville, N.C.

NNAMDITaking your calls at 800-433-8850. Tom, you got an email from John in Harpers Ferry. "Are there weather-tracking tools that anyone can buy and use? Can I set up an observation station and help provide data into the system?"

TULOUYes. There are a number of individuals who participate in observing programs. There are programs that range from K through eighth grade called the global observing program -- globe program. This is a activity that students in schools can actually participate in. There are private networks, CoCoRaHS is one in particular. It's got an interesting name. It's a cooperative observing activity run out of Colorado, but it's nationwide.

TULOUAnd there is a cooperative weather observing program that NOAA sponsors where there several thousand observes across the U.S. So, indeed, there's a couple of ways to enter into this activity.

NNAMDIChris, one of the issues that we're looking at -- I should say Christophe -- is our rising sea levels, one of our more serious challenges. In particular, what would that mean in this area? We're also looking at heavy rains in this area. You talk a little bit about those.

TULOUFlooding risk is one of the key signatures of changing climate in part because the ocean water is warming up and expands. Ice caps are melting, providing a -- as yet hard to predict amount of water to the world's oceans. But if they were to max out in terms of their melting, that could increase the level of the ocean by several meters. So, you know, for a city like Washington and other coastal cities, and if you look at the map of the world, all of our largest cities and concentrations are in coastal areas, highly vulnerable to flooding.

TULOUAnd so there's two kinds. There's the sea-level rise associated flooding and storm surge flooding, which is a real problem when we have a hurricane or a northeaster coming up the coast, for example. And we have to protect ourselves against that. And there is, interestingly enough, on the National Mall, unbeknownst to most people in D.C., a levy that protects a huge lot of D.C. through the monument and museum section of the central city and down into southeast.

TULOUThat is, that's flood gate, right there at 17th Street, just south the Constitution Avenue. And so the levy is being, shall we say, strengthened and heightened to with a core of engineers taking the lead.

NNAMDIWe've got a map of D.C.'s floodplain on our website provided by Christophe's office. Thank you very much. And you can see the levy on that map. So if you go to kojoshow.org, you can find it right there. Again, the number is 800-433-8850. John Henz, how does population growth -- Christophe talked a little about where people choose to live. But how does population growth and where those people choose to live add to the challenges when bad weather hits?

HENZWell, I think one of the things we don't think about is that all the delivery systems for water and energy into our cities were probably designed over 30 to 50 ago. And when you look at 30 to 50 years ago and the way we use climate information, we consider climate to be sort of a stationary thing. You get about 30, 40 years of data. That'll define everything that can possibly take place.

HENZAnd as Christophe pointed out very effectively, and Tom also, we've learned now that climate is a dynamic and that it's an evolving thing and that we've been able to measure these things. But the population centers and the fact that coastal areas especially are such wonderful places to live, we've gotten to the point where the population may be burdening the delivery system.

KARLSo that while the system may have been designed to handle heat waves and droughts that happen maybe at 100-year frequency or whatever, the populations increase so much and we haven't improved that delivery system very much, that even a 20-year storm, as well call it, a storm we'd see every 20 years, maybe even 10 years is starting to cause brownouts, delivery problems and challenges for people in those areas.

NNAMDIDoesn't take 100-year storm anymore, huh?

HENZNo, it doesn't. In fact, I'm sure if we take a look at the weather just along here in Washington, D.C., over the last number of years, we can see where the challenges have mounted up. I know I worked on the flood warning system for the city of Fairfax, Va. And in working in that, just as Christophe pointed out, storm surges coming up the Potomac hurricane passage, the delivery and excess of water caused people in their area to design a flood warning system that was very interactive with the public.

HENZAnd getting the public aware of this was a major thing 'cause they hadn't thought about the fact that the lake right in their backyard was actually used to protect them as much as -- and in some cases provide water as it was just a recreational facility. But I do think that the population has increased so significantly that even hurricanes and hurricane sensitivity has increased in the Gulf Coast, Florida, all along the eastern seaboard.

HENZAnd when I did work in -- excuse me -- San Francisco, they were very concerned about the sea level rise issue because population that had grown into popular areas of the Bay Delta were having impacts on the availability of water and also the people that were being subjected to flood threat and the fact that -- I don't know if you mentioned it, Christophe, but the salinity in our water is increasing also when we have sea level rise, and that's another factor to look at. But certainly...

NNAMDIJohn Henz, a senior meteorologist and technical leader for Dewberry Consultants. He joins us from the studios of KFCR in Denver, Colo. Joining us in our Washington studio is Christophe A.G. Tulou, director of the District of Columbia's Department of the Environment, and Tom Karl, director of the National Climatic Data Center, NCDC, based in Nashville, N.C. We go to the phones. And Roland in Washington, D.C., you're on the air, Roland. Go ahead, please.

ROLANDWhy, thank you, Kojo. It's a pleasure to talk with you and your guests today. I don't want to answer the climate -- global warming debate. But I just wanted to have a few questions flagged. You look through the history of climate meteorology, what we discover is it's nothing -- there is no stability. I mean, it's invariable from -- in micro periods and in macro periods.

ROLANDWe go back from the 1250, I guess, to about 1850, you had the (word?). You had the little ice age, previous to that, the medieval warming periods. You know, the problem is I think through '50s, '60s and '70s in our lifetimes and our institutional memories, we saw a sense of -- probably a little bit more of a stability in the weather patterns, and we're trained to make comparisons to that.

ROLANDAnd I just throw up a question flag on that because our weather has been variable. Just look through the geological record, and you'll see from, you know, some -- literally from 4 billion years ago but more realistically in the last four or 500 million years, a significant changes in climate. What we have to be really careful about is the difference between precision and accuracy. Today, we can measure weather within a tenth, you know, hundredth or a thousandth of degree.

ROLANDWe go back 50, 70 years ago, it's a plus or minus 1 1/2 degrees. We cannot make precise measurements and comparison with today's weather but the historical weather did 50 years ago or even 200 years ago and so forth. Anyway, I just wanted to make that comment and see what your guests have to say about that, the difference between precision and...

NNAMDITom Karl -- and, Roland, I appreciate the comment -- what should I be inferring from Roland's comment?

KARLWell, I think Roland makes some good points. And one of them, he talked about some climatologists have talked about the '50s, '60s and '70s as being almost like a climate optimal for the U.S. And, you know, we did produced a lot of infrastructure during that time period after World War II. And if we look at the -- we have something called a climate extremes index that we've put together, looking at various extremes.

KARLAnd certainly that period shows up as being pretty nascent in terms of not much going on relative to what we're seeing today. But one thing I would point out, we have to be careful about talking about the time scales of change going back, you know, tens of thousands of years and 400 million of years. The rates of change we're seeing today are pretty spectacular and the kinds of projections that scientists feel are more likely they're not to occur this century are faster than any changes that we've seen in recorded human history.

KARLSo it really then challenges our infrastructure, our capability to adapt and plan, you know, this is what is going to keep Christophe up at night trying to figure out how to keep Washington safe.

NNAMDIBut on the other hand, you also point out, Tom, that one challenge is that the past, say just looking at the last decade, may no longer be the guide to the future. Can you explain?

KARLAbsolutely. We -- for example, we've -- John had mentioned the energy industry as being particularly interested in trying to anticipate what they might expect the next few decades. We put out something called climate normals. And normals, as John mentioned earlier, are very useful if the climate is expected to be the same in the next few decades as they were in the previous decades.

KARLWhat we've come to realize, we have new normals now, and they are constantly changing. And it's uncertain as to how we can accommodate that change 'cause you have to anticipate that the conditions in the future aren't going to be like what they were in the past. The energy industry, very interested in energy generation and transmission.

KARLThey've told us they're very sensitive to these high temperature extremes, the capability of transformers to sustain very high temperatures, the sagging of the lines and the efficiency of moving energy around are all impacted by these temperature extremes. So it presents a real challenge to figure out how we're going to use this past information and the information we think is most pertinent to the future.

NNAMDIChristophe.

TULOUAnd I think that this is also irrelevant in the insurance side of things. The way risk was valued and predicted was based on what happened in the past. So it's very actuarial. It was like how many loses do we have last year and the year before. And then our premiums would be based on that level of risks. That's not working there either. What we're seeing is catastrophic loses and insured loses increasing decade by decade at incredible rates.

TULOUAnd the insurance industry is just as interested as Tom and folks who rely on their data and predictions in knowing what that future holds. And they can't rely on the past anymore. So what we know in the climate side with regard to wind and flooding risk is that we can't depend on the old tools and we need to develop new ones because indeed climate is changing. And it's changing and pretty much a unidirectional pattern towards higher temperatures, increased rain events, other things that we all are concern about, have to insure ourselves against.

NNAMDIJohn Henz, care to chime in?

HENZYeah. I actually think that the thing we need to keep in perspective is that, as Tom pointed out, the instrument of period of record that we have really was satellites and where we have a fairly good idea, the three dimensional and time scales may only go back, what would say, Tom, maybe about 25, 30 years back into the '60s and '70s?

KARLYeah, where we really have good three-dimensional observations. We can go back farther for some elements, but good comprehensive, that's right, John.

HENZYeah. And then you have to go back to the 1700s for temperature and pressure. And so, in many ways, our climate science and services are still an emerging science, and we're still learning how to utilize all of this information not only to understand its impact today but how you project that into the future.

HENZAnd I think it bodes well for many of our young people that are looking for challenges today, that they can mix and mingle with those of us that have a little bit of white hair on top of our head and interact with businesses and others at utilizing some of the new science that's coming out and utilize it to make a better community, especially in our coastal areas and in our large metropolitan areas, how to do things better.

HENZAnd I think right now that the challenges are laid out in front of us. I do know that, speaking to the insurance industry, I used to do forecast and outlooks five years in advance for risk on various things, for some of the large insurance companies, back in the 90 -- late 1980s into the 1990s, and they continue to do this. And so I agree with you, Christophe, that many of them look at it from an actuarial standpoint.

HENZBut they were trying to recognize the fact that risk changes even five years down the road. And if they can get out of an area where they see a high risk, they might do it. And that occasionally takes place in things such as drought or areas prone to hurricane activity, as we've seen, especially in the state of Florida, which has seen the insurance coverage and the rates change dramatically. But as we have these large population centers and very risk-prone areas, it makes the challenge that much more exciting for everyone.

NNAMDISpeaking of the state of Florida, we are heading off to the Republican National Convention this weekend. Tom Karl, John Henz, Christophe Tulou, what can you tell us about what we might expect there from the possibility of Hurricane Isaac?

KARLWell, it's a little bit far off to say exactly what the likelihood of being affected in Orlando will be where -- it's not Orlando.

NNAMDIIn Tampa.

KARLIn Tampa, sorry. But, you know, we can say, climatologically, this is the time of the year when storms do make their way into the Gulf, and then they make their way inland. But it's a bit too early to make any call on that one. But I -- one thing that might be worthwhile, in light of the conversations that we've had, you know, in order to really better understand climate and help us out with these hurricane tracks, climatologically speaking, there's a huge technology challenge for us related to big data.

KARLJust to give you an idea, just my center alone sent out enough data last year, which would be equivalent for an e-book for every person on the planet. Now that's a lot of data. And the trick is make sense of those data in ways that are intelligent. And so I think if anyone is looking for a challenge, there is a big data challenge out there. Once you get the technology, make the observations using that data, and then combining them with our understanding and models. It's a tremendous opportunity for us to learn about the future.

NNAMDIGot to take a short break. If you have called -- and several callers would like to join this conversation -- please stay on the line. We'll try to get to your calls as quickly as possible. If the lines are busy, go to our website, kojoshow.org, join the conversation there or send us a tweet, @kojoshow, using the #TechTuesday. Or you can revert to email. Just send an email to kojo@wamu.org. Where do you get your weather information? Do you think it's gotten more accurate? I'm Kojo Nnamdi.

NNAMDIIt's Tech Tuesday, and we're talking with Tom Karl, director of the National Climatic Data Center in Asheville, N.C., who happens to be in D.C. today for meetings, and we're glad about that. We're taking advantage of his presence here to discuss climate services and changing weather with Christophe A. G. Tulou, director of the District of Columbia's Department of the Environment, and John Henz, senior meteorologist and technical leader for Dewberry consultants.

NNAMDIWe're taking your calls at 800-433-8850. We'll start with Steve in Gaithersburg, Md. Steve, you're on the air. Go ahead, please. Hi, Steve. You there?

STEVEHi, Kojo. Yeah. Thanks for taking my call. I just had two quick questions for the panel: how the engineers and meteorologists are preparing the private sector and the local governments for the solar storms, and if they expect it to be like a one-time event, minimal damage that can be recovered within a week or so. And I'll take my answer off the air. Thank you.

NNAMDIFirst, Tom Karl, what do we know about solar storms that apparently our caller is expecting?

KARLWell, first, let me qualify. I'm certainly not a what we call space weather expert. But we are coming out of a cycle where we have had minimum solar storms, and now we're on the upswing. And so the expectation is that, over the next number of years, solar storms will become more frequent.

KARLAnd obviously they're important because they have the ability, when they're strong enough, to disrupt communications, and communications being so critical for us. And it's something that has captured a lot of attention in terms of ensuring the most powerful storms don't not only affect communications, but affect energy transmission and knock out power.

NNAMDIHow do you plan and design for the unknown in a situation like solar storms, Christophe?

TULOUFrankly, I don't know.

NNAMDIThat's a refreshing answer to a question on this broadcast.

TULOUYeah.

KARLExcellent.

TULOUWe -- we're very reliant on our utilities, certainly thinking that Pepco would have a great interest in potential implication on transmission of electricity and Verizon and its implications for communications, of course, all the wireless providers and how -- and obviously as a, you know, as a beneficiary of their services, very interested in knowing how they're doing. We do have an office of the chief technology officer for the District of Columbia that I'm sure is keeping an eye on those issues, just like cyber security and other things that they need to worry about.

NNAMDIAnd, John, I suspect this is something that businesses are also concerned about.

HENZWell, I've been part of the meteorological engineering community nexus, if you will, for about the last decade and a half. And I know at Dewberry and -- we have had an opportunity to interact with others. And I think the question is a good one. The electrical community and communications community and utilities communities are all aware of this. And we have a very effective space forecast center in Boulder, Colo., which is providing services not only to our astronauts that are up there, but also to the communication satellites that we all rely on.

HENZAnd the GPS in our cars or in our phones are all coming from satellites up there, so we have to be very aware of it. There is a certain amount of over-engineering in the system to try and handle the extreme events that you might see in a solar storm. I, too, am not an expert in that area, but I know that the engineers who are have tried to build those into it. But, at the same time, they know that we still have a vulnerability, and that's because of some of the older infrastructure that's still out there that hasn't been upgraded.

HENZSo I don't know if we really have an answer to your listener that's definitive, but I do know that they plan for it to the best that they can. And we all have to wait and see what happens, won't we?

NNAMDIHere is Don on the Eastern Shore in Maryland. Don, you're on the air. Go ahead, please.

DONYeah, thank you, Kojo. Yeah, I'm down here by Ocean City. Back in the early '60s, we had what we call the March storm, and we had, like, eight foot of water in the house that I grew up in West Ocean City from that storm. And since then, I understand that the sea has risen about 11 inches. And then with the climate change and everything, they're talking about another 33 to 36 inches of sea level rise. And if you look at Ocean City, Beach Highway is probably, I would say, maybe five feet above normal high tide.

DONAnd the lower end of town, of course, that floods out whenever it rains. And if we've got a good moon tide and the moon's, you know, making the tide higher and it rains, it can be anywhere from two to 2 1/2 feet high at the south end of town. And in the north end of town along Beach Highway, you might have a foot that's unable to exit because of the high tide.

NNAMDIAnd your concern, John, is? Don?

DONWell, with the sea level rise on the Eastern Shore, you add three feet of water between now and 2100, they say, you're going to have places around the Eastern Shore that are only going to be accessible by boat, towns and the like due to their low marsh area and everything else.

NNAMDITom Karl, is that a possibility, a likelihood? And then, Christophe, how does one plan for that? But go ahead, please, Tom.

KARLKojo, that was a great way of framing it. Certainly, it's a possibility. And one of the things -- the science right now isn't really clear on providing likelihoods for as much as, you know, a three-foot rise along the East Coast. But what we can say is, given our current understanding, there are some levels of sea level rise for which we are pretty confident you need to prepare for, and that is that sea level rise that's due to the warming of the ocean temperatures.

KARLAnd that's dependent on how much the greenhouse gasses we continue to put into the atmosphere. This other part that Christophe mentioned earlier, melting of Greenland ice sheet in Antarctica, is much more difficult to understand. We don't have models yet that can model that, understand all the dynamics. But if their contribution continues to be substantial, as some have suggested, then the possibility of three feet becomes more real.

NNAMDIAnd, Christophe, how does a jurisdiction try to prepare for that kind of thing? Christophe is holding up something called the Washington D.C. elevation map.

TULOUYeah. And Ocean City is just a typical example of a poor coastal city that is sitting very, very close to sea level. And we have vast lots of Washington, D.C. that are, you know, six, seven feet or lower relative to normal sea level. Let's just put this in perspective. It doesn't matter what climate change is doing. Any given storm, let's say a category one, two or three coming up the coast, could push as much as 10, 12, 15 feet of water ahead of it, depending on some various factors. That's going to create havoc in any coastal community.

TULOUIt would create havoc here in Washington, and those are the sorts of things that we can anticipate because they will happen. What climate change is doing -- and we do have a record of data that is indicating that sea levels are rising. And we have every reason to expect that that increase will -- rate will increase over time simply because that's what the climate science is telling us we can expect in terms of warming of the atmosphere. The warmer the atmosphere is the warmer the ocean is going to be.

TULOUThere's no reason to expect that business as usual in terms of pumping CO2 and other greenhouse gasses in the atmosphere is going to change anytime soon. But the climate change that we see now in terms of sea level rise is a reality that we'll have to live with as a globe for decades to come. That is not going to stop if we stop producing greenhouse gas tomorrow. So any amount, in addition to what we have as a base level, sea level right now, is going to increase the risk, the threat and the damage that's going to occur in coastal communities like Washington when those storms come along.

NNAMDIDon, thank you very much for your call. On to Bill in Silver Spring, Md. Bill, your turn.

BILLHi. Good afternoon, everyone.

NNAMDIGood afternoon.

BILLMine is very related to the caller who just called in from Ocean City in that, you know, looking at it realistically, you can expect the big cities -- New York and the ports areas like Baltimore and other places -- to pretty much deal with this by armoring, you know, putting up flood walls and growing to whatever to protect themselves. However, you can't armor the entire U.S. coast. I mean, it'd take millions just to armor D.C., much less all the other cities that are around on the coast.

BILLAnd so the rural areas are going to get, for lack of a term, better term, they're just going to be, you know, kind of cut loose because we can't afford it as a country, much less anybody else in the world afford it, to really armor the entire coastline for sea level rise. And, you know, with the temperatures rising and everything else, there's basically no one that I can see sitting back saying how are we going to protect these people?

BILLAre we going to have to move them inland? Are we going to have to move entire towns? Are we going to have to, you know, address various factors? Like, if you leave these towns, what happens to the old area that may be polluted due to gas stations...

NNAMDIBill, I'm glad you raised that question because we're talking so far in this conversation as if we are the only country in the world that might be experiencing these kinds of problems when, in fact, Tom Karl, climate and weather are obviously not restricted to a single country. How do the U.S. and other countries work together not only on whether and climate information, but I'm talking about possible solution to some of the kinds of problems that Bill is talking about?

KARLWell, that's a great question. Just two years ago, other world governments got together in Geneva to talk about climate services and how we can adapt to a changing and varying climate. That has progressed over the last couple of years. There was a meeting last year in New York. A number of governments were there to try and see how we can better provide data and information models to help with the adaptation. There's another meeting planned again this year in Europe.

KARLA lot of the private sector components will be represented at that meeting. So there's a world community out there trying to understand and better grapple with this problem, and there's recognition that, you know, it is an interconnected problem. No one country can do it on their own.

NNAMDIWe're almost out of time, John, but we got an email from Chad, who says, "I prefer using Weather Underground because of the ability to get local weather data. What would be the best way of getting or predicting a long-term whether forecast, about three to five months in advance?"

HENZWell, you sure asked an interesting question because...

NNAMDI30 seconds to that.

HENZThe 30-second answer is that if you go on the Internet and Google, you'll probably put in those terms and come up with a variety of private federal state and university areas that could provide the information. But to the previous caller, I want to quickly, Kojo, mention that states are working to identify areas where coastal sea rise are going to have problems. They're working with engineering companies. I know that Dewberry were working on a number of these projects in states where they're trying to figure out where to move people when the risk is going to be the highest.

NNAMDIJohn Henz is senior meteorologist and technical leader for Dewberry Consultants. Thank you.

HENZThank you so much.

NNAMDIChristophe Tulou is director of the District's Department of the Environment. And Tom Karl is director of the National Climatic Data Center, NCDC, in Asheville, N.C. Thank you all for joining us. And thank you all for listening. I'm Kojo Nnamdi.

On this last episode, we look back on 23 years of joyous, difficult and always informative conversation.

Kojo talks with author Briana Thomas about her book “Black Broadway In Washington D.C.,” and the District’s rich Black history.

Poet, essayist and editor Kevin Young is the second director of the Smithsonian's National Museum of African American History and Culture. He joins Kojo to talk about his vision for the museum and how it can help us make sense of this moment in history.

Ms. Woodruff joins us to talk about her successful career in broadcasting, how the field of journalism has changed over the decades and why she chose to make D.C. home.